A Rough Year for Parcel Taxes

This was a rough year for parcel taxes: voters rejected all but two of the seventeen parcel tax measures that school districts had proposed. This is not surprising, given the economic climate, but it is disappointing nonetheless. Compared to school districts in other states, California districts have very little local control over their level of revenues; aside from voluntary contributions, the only way districts can really raise additional revenue (above what the state allocates) is by passing a parcel tax. Parcel taxes are flat taxes per property parcel, regardless of the size, purpose or value of the parcel, and they must be earmarked for a specific purpose.

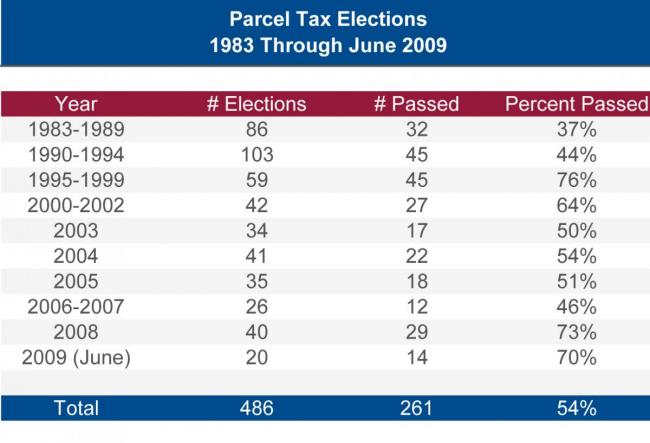

Between 1983 and June 2009, voters approved 261 parcel taxes in 486 elections (passing an average of 54%). As shown in the table below, parcel tax elections have been somewhat more common in the last decade, and those in the last couple years have been particularly successful.

The total number of parcel taxes and parcel tax elections obscures the fact that only a relatively few districts have even attempted to pass a parcel tax. The 486 elections represent only 194 districts (obviously, some districts have had multiple elections), and of those, only 98 districts have been successful. For example, Piedmont City Unified in Alameda County has proposed and passed eleven parcel taxes over this time period.

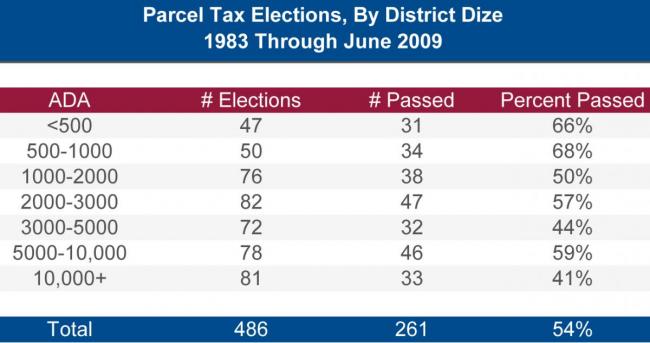

Brunner and Sonstelie (2006) make the point that parcel taxes have been most successful in smaller, higher-income communities. Only 19% of the elections between 1983 and 2009 were even held in districts that were above the state average of percent low-income students, and of those, only about a third passed; in contrast, 58% of the elections in higher-income districts were successful. The number of elections has been relatively evenly distributed across districts of various sizes (see table), but the success rate in smaller districts is much better.

See Brunner and Sonstelie study: “California’s School Finance Reform: An Experiment in Fiscal Federalism”, University of Connecticut working paper 2006-09."

* Many analysts are fond of statements such as “X of those taxes would have passed under a 55% threshold (or Y would have passed if only a simple majority were required)” but I feel such statements are somewhat misleading, since it is impossible to say what the vote would have been if the vote requirement had been different. For example, if the vote requirement were lower, it is possible that both supporters and opponents would be motivated to spend more on campaigning and some non-voters (either supporters or opponents of the tax) might have been more motivated to vote.