Rethinking Chronic Absenteeism in California

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of students in the United States were chronically absent from school (i.e., missing 10 percent or more of school days). The pandemic only exacerbated the issue, and while there has been some progress during the last few years, chronic absenteeism rates remain far above prepandemic levels. In California during the 2023–24 school year, 20 percent of students were chronically absent, compared to 12 percent before the pandemic. Chronic absenteeism rates are high in urban, suburban, and rural districts alike, and they are especially high in schools with more socioeconomically disadvantaged students.

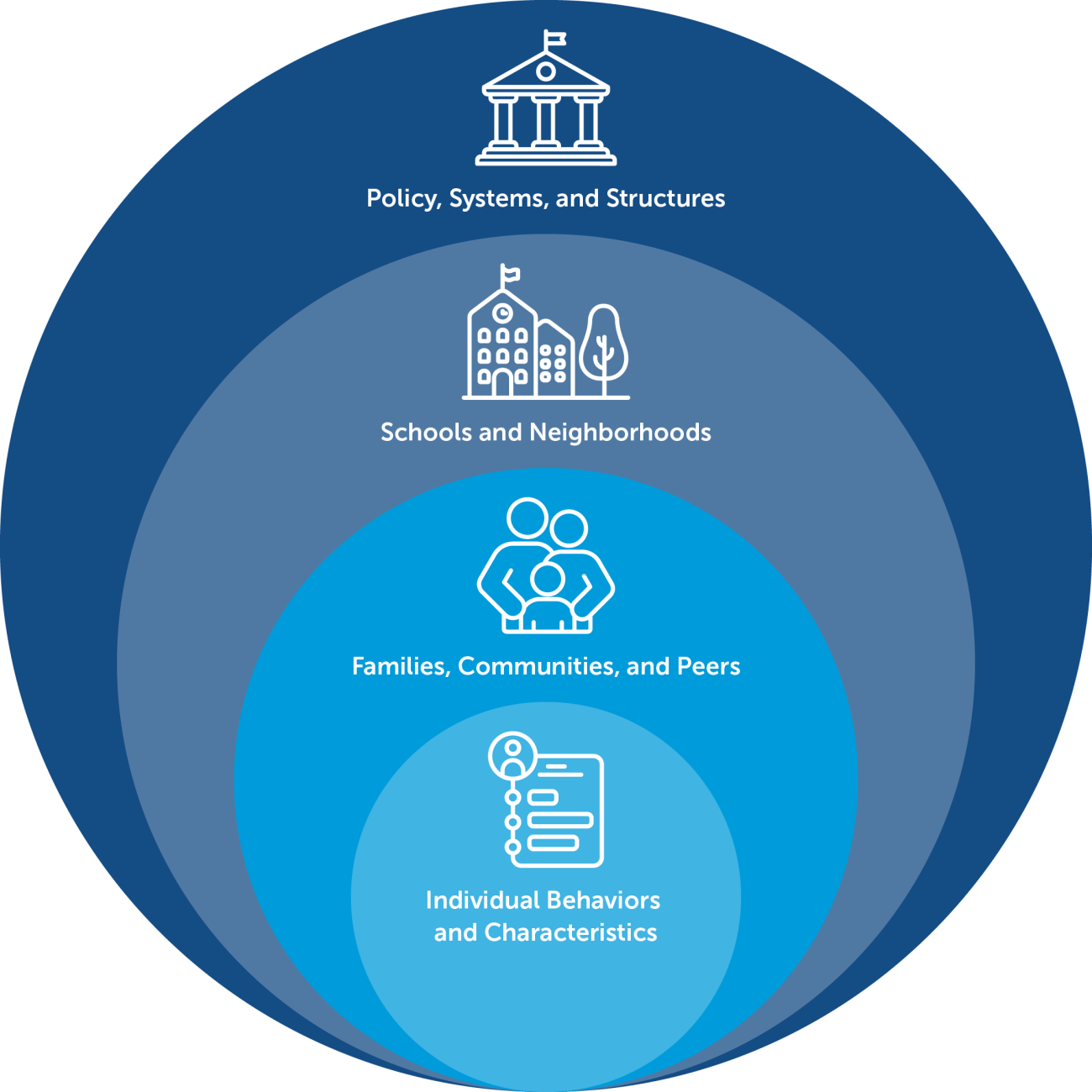

We have been studying the causes and consequences of chronic absenteeism in Detroit, Michigan, as well as various district- and community-based efforts to reduce it, for nearly a decade. Our research, alongside other evidence on attendance interventions, has led us to a simple conclusion: Schools cannot solve the issue of chronic absenteeism alone. Chronic absenteeism is an “ecological” issue, meaning that a complex combination of factors can lead to attendance problems (Figure 1). Those factors will vary among students and families and may even differ for the same students over time. But broadly speaking, the barriers to regular attendance that many students face are due to a combination of family, school, and contextual factors, often resulting from or exacerbated by social and economic inequalities. Deep social inequality creates extremely challenging conditions for student attendance in places like Detroit and in many districts across California. Districts and schools have only certain tools and resources available to them, which are not necessarily aligned with or adequate for alleviating the barriers to attendance that many families face. This is especially the case in high-absenteeism districts, given the magnitude of chronic absenteeism, but it is also true in all school districts, where supplemental resources and services are often necessary to meet families’ needs.

Figure 1. Attendance as an “Ecological” Issue

The lessons from our work can help California continue along the right path toward improving student attendance. According to a recent analysis, the majority of schools in California have either a “high” or an “extreme” chronic absenteeism rate, which highlights the usefulness of learning from other high-absenteeism contexts. We have found that the strategies adopted in Detroit are increasingly common in other districts in Michigan and throughout the country. Thus, while Detroit represents in many ways a unique context for chronic absenteeism, the experiences of educators, leaders, and families there can help inform California’s approach to improving attendance and reducing chronic absenteeism.

Limits to School-Based Solutions for Chronic Absenteeism

There are absolutely things that schools can and should do to improve student attendance. But because high rates of chronic absenteeism are driven by social and economic inequalities that are outside the scope of schools or districts to address alone, focusing only on school-based efforts will not lead to dramatic increases in attendance. Indeed, we know from existing research that the practices most within schools’ grasp are unlikely to have a large impact:

- Effective communication nudges have a small positive impact at most.

- High academic standards may have a small positive impact.

- Incentives have little supportive evidence and may even have negative impacts.

- Positive school climate is associated with better attendance, but the causal relationship is unclear, and positive effects are likely small.

- Court-based action (both truancy prosecution and truancy diversion) has been ineffective.

- Intensive casework and community schools can make a bigger difference, but these are personnel- and resource-intensive practices.

As we document in our book Rethinking Chronic Absenteeism, schools have limited tools to address chronic absenteeism, and thus they are limited in their ability to solve the issue alone. Although schools commonly adopt models like Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) and strategies focused on incentives, communication, and outreach, we saw in Detroit how these approaches are often limited in their impact and can be implemented without sufficient attention to their effectiveness or alignment with the root causes of absenteeism. While MTSS can help schools organize their attendance strategies, it often leads educators to conflate intervention tiers with specific solutions for absenteeism. This can lead schools to prioritize universal strategies that are not well aligned with the specific attendance barriers that a student faces. Further, because of the complexity and magnitude of the issue, attendance-based personnel and school staff are often burdened with conflicting and unrealistic expectations. This can result in burnout, frustration, and reliance on more punitive approaches, dovetailing with common misperceptions that chronically absent students and their parents are uninformed, unmotivated, or irresponsible. Ultimately, educational strategies alone are insufficient to solve the issue of chronic absenteeism and must be complemented by broader efforts that address the social and economic conditions driving absenteeism.

A Broader Approach to Solving Chronic Absenteeism

To solve the problem of chronic absenteeism, we need to address it as a societal problem rather than an educational one. Policymakers and community leaders must commit to improving the conditions for student attendance outside of school, just as schools are committed to improving conditions inside schools.

This means that policymakers must allocate additional resources and facilitate collaboration across multiple sectors (e.g., health care, housing, transportation, social services) to meet students’ and families’ needs. There is no getting around the fact that deep social and economic inequalities are the fundamental cause of high chronic absenteeism rates in districts like Detroit, such as the many California districts with “high” or “extreme” chronic absenteeism rates. Cross-sector coordination is a necessary condition for connecting families with resources and services that can remove barriers to student attendance, but better coordination alone will be insufficient in many contexts. Thus, to truly address chronic absenteeism, policymakers must make substantial investments in reducing material inequalities—for example, by increasing families’ economic security, housing affordability and stability, access to health care and healthy environments, and access to transportation. This can be done through a combination of new resources and services provided directly to families, investments to improve existing systems and programs, and more coordination between school systems and other policy sectors. Assembly Bill 2083, Foster Youth: Trauma-Informed System of Care, while focused on serving children and youth in foster care, offers a compelling vision for how greater cross-agency and cross-sector coordination among can improve support for children and youth in California.

In California, policymakers should consider how to strengthen the conditions for student attendance by building on evidence-based strategies already in place in many districts, expanding resources and coordination in others, and considering how sectors outside of schools can coordinate their efforts more strategically. For instance, California is already leading the nation in investment in community schools through the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP). There is strong evidence that the resources, coordination, and relationship building embedded in the community-schools approach can have a positive effect on school attendance. California could further leverage this investment by specifying responsibilities for California’s County Offices of Education (COEs) as they award CCSPP coordination grants. COEs are well positioned at the nexus of school districts, county agencies, and community-based organizations to take active leadership in cultivating and coordinating cross-agency and cross-sector partnerships that address root causes of chronic absenteeism and achieve economies of scale for community schools within their jurisdictions.

Another major barrier to regular school attendance is transportation, and California ranks at the bottom of all the states in the continental U.S. when it comes to the percentage of students with access to school transportation. Long commutes, unreliable transportation, and unsafe conditions on the way to school can all contribute to chronic absenteeism. California should consider expanding both public and school transportation to ensure that more students have access to a safe, reliable way to get to school. Policymakers should also consider ways to reduce the transportation burden for families, such as by expanding access to before- and afterschool care, incentivizing employers to accommodate employees who need to drop their children off at school or pick them up, or requiring schools to offer transportation to students who meet certain criteria (e.g., distance from home, economic need).

California is one of few states that allocates school funding based on students’ average daily attendance. This means that schools with the highest rates of chronic absenteeism are financially penalized, potentially making it even more difficult for them to address the causes of absenteeism in their communities. This approach raises significant equity concerns because schools with high chronic absenteeism are more likely to be serving more students who are economically disadvantaged, have unstable housing, qualify for disability services, or are migrants. The schools often lose funding precisely when their need for resources is greatest. Addressing chronic absenteeism effectively will require rethinking how funding formulas can both promote attendance and ensure adequate, stable resources for schools serving the state’s most vulnerable students.

Finally, it is important to address the consequences of immigration raids and deportation efforts for students in California. Prior research from California and across the U.S. has shown that immigration raids lead to immediate and sustained increases in absenteeism. A recent study found that immigration raids conducted in California’s Central Valley during the 2024–25 school year led to a sharp increase in absences for students in those communities. While policymakers explore a range of options to manage interior immigration enforcement appropriately, district and school leaders can prioritize creating safe, welcoming, and responsive environments for immigrant-origin students—including protections for privacy and access, culturally responsive curricula, visible displays of support for immigrant-origin students and families, strong family engagement and communication, and trauma-informed training for school personnel.

More generally, schools and districts should address factors within their locus of control. First, they should focus on improving the things that are already core to their school-improvement efforts: effectively communicating with families about attendance in informative and supportive (but not punitive) ways; strengthening relationships between educators, students, and families; and creating an overall positive culture and climate. They can also work with families to understand local barriers to attendance better and either provide resources directly or connect families with available external resources and services. Schools should avoid counterproductive practices, such as an overreliance on attendance incentives and punishments. In addition, to the extent that schools employ any attendance-specific personnel, they should consider positioning these personnel as “navigators” (common in other policy areas such as housing and health care) who can help families access resources that can help alleviate barriers, rather than as generalists who focus on a variety of different school-based attendance-related tasks.

Conclusion

When districts are left to tackle chronic absenteeism without cross-sector support, even well-intentioned strategies fall short. School-based efforts are important—and schools should continue to build strong relationships with families, create welcoming environments, and improve internal practices. These strategies must be supported by broader systemic efforts that address the social and economic conditions at the root of chronic absenteeism.

California has already begun investing in promising models, such as community schools, but must go further by expanding transportation access and ensuring that county and state agencies actively support districts in meeting families’ broader needs. Only through coordinated, multisector investment in the conditions that make attendance possible—housing stability, economic security, health access, and safe transportation—can California expect to see meaningful, sustained improvements in school attendance statewide.

This commentary was adapted in part from an essay published at the Fordham Institute as an entry in its 2024 Wonkathon. The authors' book on the subject, Rethinking Chronic Absenteeism: Why Schools Can’t Solve It Alone, was published by Harvard Education Press in March 2025.

The authors thank Jeannie Myung for her guidance and support of this commentary.

Lenhoff, S. W., & Singer, J. (2025, July). Rethinking chronic absenteeism in California [Commentary]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/rethinking-chronic-absenteeism-california