Why Aren’t Students Showing Up for School?

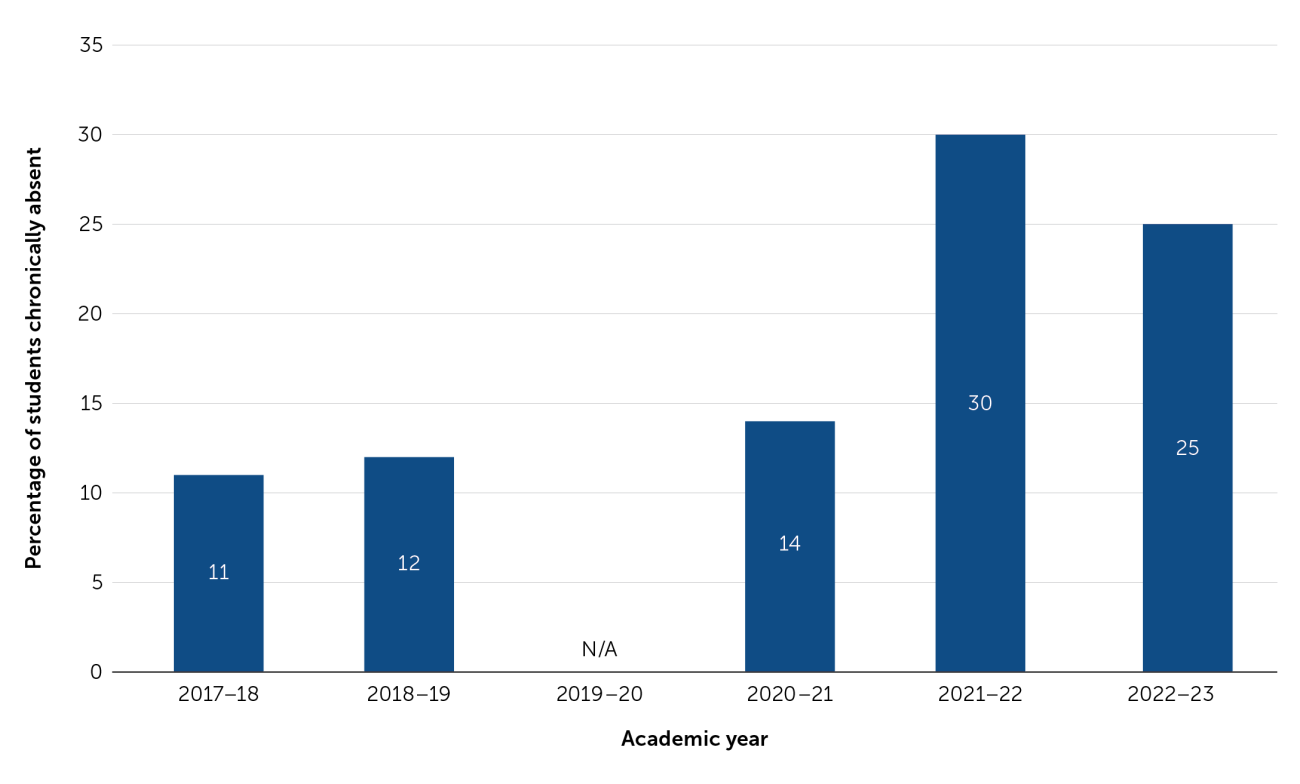

The surge in chronic absenteeism among California students during the 2020–21 and 2021–22 school years was initially attributed, quite reasonably, to the challenges posed by the ongoing pandemic. There was optimism that these rates would eventually begin to decline as schools returned to normal. When new chronic absenteeism numbers came out in October—along with California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASSP) data for 2022–23—the findings indicated that rates are down from the soaring absenteeism of 2021–22; as shown in Figure 1, 25 percent of K–12 students in California schools were chronically absent in 2022–23, down from 30 percent the year before. However, more than three years after the initial onset of the pandemic, chronic absenteeism among California students is still double the rate of prepandemic levels, and there are no signs of this trend abating.

Figure 1. Chronic Absenteeism in California’s Schools

Acknowledgement of the crisis that these attendance patterns pose to public education is growing. “It’s worrisome that kids are still staying home from school in record numbers,” Assembly Budget Chair Phil Ting (D-San Francisco) has said. “Our investments in universal school meals, after-school programs and home-to-school transportation have not been enough to bring students back. … We need to understand why attendance is below pre-COVID levels, so that we can better direct state resources and education leaders where they’ll be most effective in re-engaging students.”

Leaders in the California Assembly reached out to PACE in spring 2023, seeking guidance on possible state-level initiatives that would improve both attendance and engagement in school for the short and long term. To inform the recommendations, PACE convened a workgroup of state leaders to identify solutions to address chronic absenteeism at scale. PACE also conducted a series of interviews with educational leaders from districts and schools throughout California as well as with organizations representing students and families. The primary objective was to gain insight into the underlying reasons for student absenteeism and to determine the essential factors required not only to bring students back to school but also to foster their active engagement in learning.

Through these interviews, PACE identified the many societal and contextual factors that have influenced student attendance postpandemic. Perhaps most importantly, since the pandemic there seems to have been a cultural shift in expectations among students and families about school attendance. With so much time out of school during COVID closures, many students and families now consider attendance optional rather than compulsory. It does not help that weather-related disasters and staff strikes have periodically closed schools across the state, perhaps reinforcing this narrative. In addition, attitudes about sickness and attendance have changed. Before the pandemic, students typically came to school unless they had a fever or were extremely unwell; now students tend to come to school only when they are wholly well. This cultural shift, along with continued elevated levels of illness, either from COVID-19 or other illnesses, has led to higher levels of absenteeism.

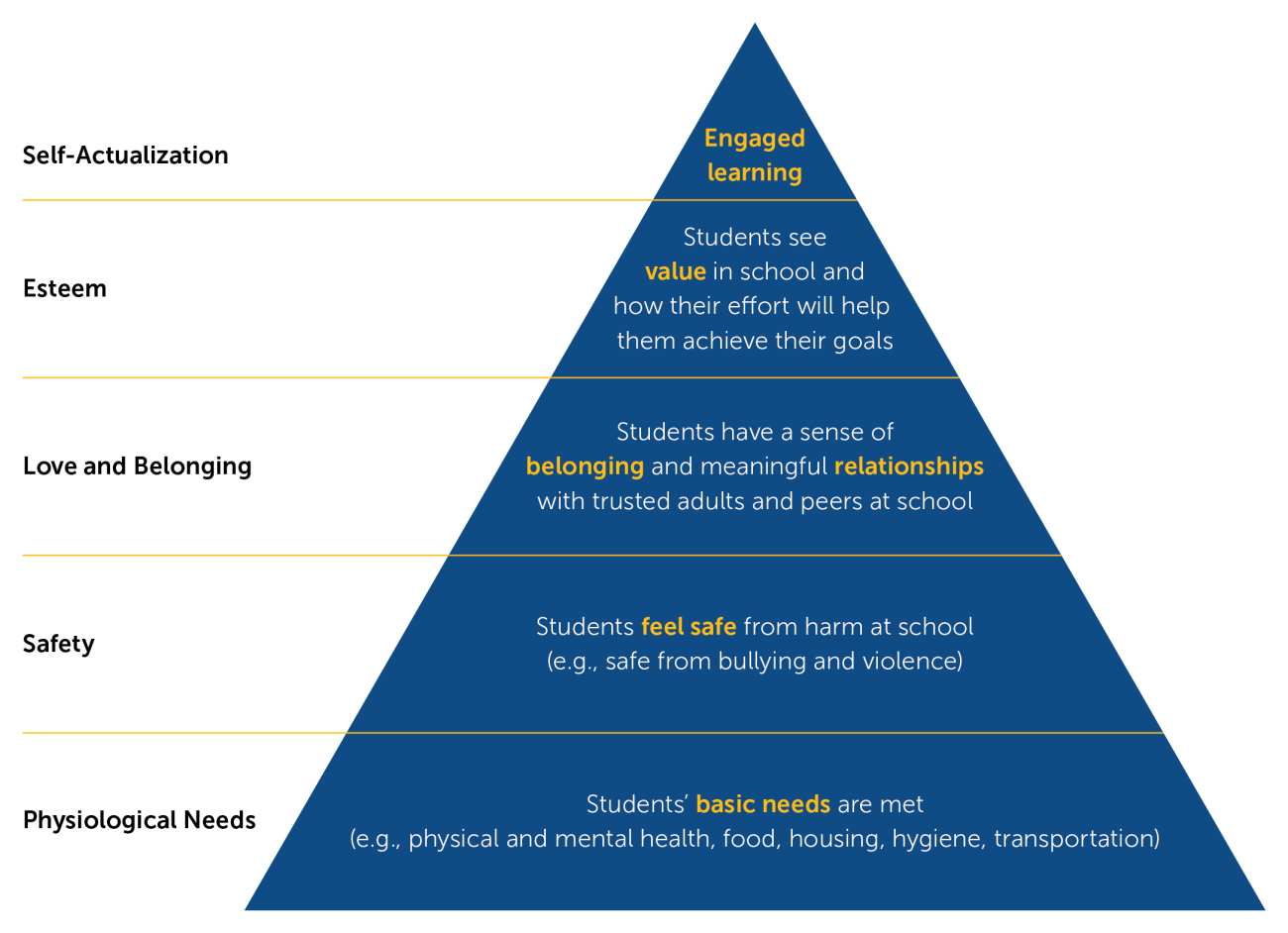

While these cultural shifts explain some of the absenteeism we are seeing postpandemic, the full picture of why students are not coming to school is much more complicated. Through our interviews, we uncovered that the main school-based factors contributing to students’ absenteeism and lack of school engagement are aligned with the theory of human motivation posited by Abraham Maslow 80 years ago. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs has received criticism due to a lack of empirical validation and an absence of scientific consensus on the ordering of the levels; nevertheless, it is a helpful framework for making sense of the wide spectrum of needs that schools can address to increase motivation for engagement in learning.

The pyramid image in Figure 2 reflects the variety of reasons we heard for why students are not showing up and engaging in school.

Figure 2. What Students Need to Show Up and Engage in School

The foundation of the pyramid addresses students’ health and basic needs; lack of stable access to basic needs interferes with students’ ability to attend and engage in school on a regular basis. While COVID-19 infection rates have subsided from their peak, a concerning trend has emerged: a surge in mental health challenges. According to district leaders we interviewed, absenteeism is increasingly driven by anxiety, stress, and social-emotional factors rather than COVID-related concerns; this spans all student age groups, with a more pronounced impact at the secondary level. This observation is reinforced by the recent findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which revealed that more than 40 percent of youth reported feeling so overwhelmed by sadness or hopelessness in the past year that it hindered their ability to engage in daily activities. Even if they are grappling with major depression, a significant number of young people remain without access to vital mental health support. Another formidable barrier to student attendance is access to transportation: students simply cannot attend school if they lack reliable means of getting there. Unfortunately, California ranks last in the nation when it comes to school bus accessibility for students. Equally crucial is ensuring that students’ basic hygiene needs are met. In response, some districts have taken proactive measures by installing laundry facilities within schools, acknowledging the need for students to access clean clothing. California has recently made large-scale investments in student mental health, such as the $4.1 billion dollar investment in the California Community Schools Partnership Program, which districts can leverage to align community resources to meet students' basic needs.

The next tier revolves around the human need for safety and security; students only want to come to school if the environment feels safe to them. Sadly, this is not the case for many students across the state and the country. Nationally, 40 percent of student respondents reported experiencing bullying on school campuses within the past year. Students subjected to bullying are disproportionately more likely to miss school due to safety concerns. Furthermore, peer behavior issues—which can be unpredictable and undermine a sense of safety for students—are on the rise. Racist, homophobic, and transphobic rhetoric has increased since the pandemic. This particularly harms minoritized students, who tend to internalize the negative messages they hear about their identities, which can be barriers to their engagement in school. While recent research in California has shown a decline over time in actual cases of severe violence within educational institutions, it is vital to remember that mass shootings, although statistically rare, cast a long shadow of terror over students’ collective consciousness. Gun violence is a concern among parents as well: in the annual PACE poll, parents consistently rate “reducing gun violence in schools” as the top education issue.

Moving beyond the foundational requirements of survival and safety, students possess an intrinsic need for love and a sense of belonging; they want to feel included and seen in school. Research finds that positive relationships with teachers in particular make students feel more safe, secure, and confident in school; while conversely, conflict with teachers can place students on a trajectory for failure in school. Student attendance is better where students report high levels of trust in their teachers and where they report that teachers provide personal support to students. However, most students do not experience this sense of trust: in the 2022–23 school year, only 22 percent of secondary students surveyed reported that their teachers understood their lives outside of school. This figure is even lower than the low prepandemic rate of 26 percent. Furthermore, research has shown that low-income students and students of color tend to feel less sense of belonging and school connectedness compared to peers within the same school. The disproportionate application of school discipline by race and gender further reduces marginalized students’ sense of belonging in school.

Beyond having their basic needs met, students also have a need to experience competence, independence, and freedom, as well as attention and respect. This is what is referred to as “esteem” in Maslow’s hierarchy. Students experience esteem when they are viewed as individuals with unique hopes and dreams, and when they are treated with dignity. This can occur when students achieve mastery in an area, when they see how their learning is personalized to them, or when they see value in what they are learning and in how it will help them achieve independence. Culturally-responsive pedagogy, incorporating greater student choice and voice, and personalized learning are components of student-centered teaching and learning that can increase students’ sense of esteem. Particular attention must be paid to ensure that students with disabilities, English learners, and students in racially minoritized groups experience educational opportunities that center their needs and assets. After the pandemic, with students and families less committed to the idea of coming to school, each day they make a determination about whether going to school is “worth it.” It is now more important than ever to make sure that the educational experiences being offered to students move beyond seat time to actual learning that is personalized and values mastery, prioritizing experiences and opportunities that align with students’ goals.

Currently, not all students find school to be a place where they experience health, safety, love and belonging, or esteem. It should then come as no surprise that these students do not feel compelled to attend school or to find school a place where they can achieve their dreams or fulfill their potential—in other words, find self-actualization. Even if students’ basic needs are met, they may feel unsafe, may not feel a sense of belonging or care at school, or may not see how their time at school is aligned with their personal goals or values. Some attendance policies focus on reminding families and students of the importance of daily attendance, and of the compulsory nature of schooling; however, conversations about how schools can address rising rates of chronic absenteeism will be incomplete without attention to each category of needs. This entails reimagining and rebuilding how California schools serve students. The first step should be connecting with families and students to understand what complex mix of factors is keeping them from school, working together to address specific challenges, and beginning the work to transform schools into places where all students can be engaged in their learning.

Myung, J., & Hough, H. J. (2023, November). Why aren’t students showing up for school? Understanding the complexity behind rising rates of chronic absenteeism [Commentary]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/why-arent-students-showing-school