Advancing Inclusive Education in California Schools

Summary

This brief presents evaluation evidence from California’s Supporting Innovative Practices (SIP) project, a statewide initiative designed to expand access to inclusive general education settings for students with disabilities. The evidence shows that districts participating in SIP—especially those with initial low inclusion rates—made substantially faster progress increasing the time children with disabilities spent in general education settings compared to state and national trends. Applied professional learning produced statistically significant gains in educator knowledge and early adoption of inclusive practices. Four key conditions support inclusive improvement: structural redesign, leadership mindset and culture, data-driven decision-making, and cross-role collaboration. The findings suggest that sustained, practice-embedded support and a systemwide, proactive approach are essential for meaningful gains in inclusive education.

Introduction: Inclusive Education and Why It Matters

Inclusive education is a systemwide strategy to ensure that students with disabilities have access to high-quality learning opportunities, experience instruction and assessment that respond to learner variability, and are meaningfully included—along with their families—in decisions about policies and practices that shape education outcomes.1 The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires that children with disabilities be educated in general education environments to the maximum extent appropriate, known as the least restrictive environment (LRE) provision of the law. While IDEA data on time spent in general education are often used as a proxy for inclusive education, this practice extends beyond a de minimis placement requirement.2 Inclusive education involves systematic approaches to organizing instruction, school structures, and adult practice so that all students, including those with disabilities, can access grade-level content, develop a sense of belonging, and participate fully in diverse learning communities.3

Although inclusive education is challenging to study causally because it is an organizational practice rather than a discrete intervention, the best available evidence consistently shows positive or neutral effects for students with disabilities educated in general education settings. High-quality quasi-experimental studies indicate that spending more time in general education classrooms does not depress academic achievement and is associated with improved long-term outcomes, including ninth-grade promotion and high school graduation.4 These findings align with broader observational and meta-analytic literature showing that when students with disabilities have access to grade-level curriculum, individualized supports, and well-designed instructional structures, they experience academic and social outcomes that are better than or comparable to peers in more restrictive settings.5 Research also indicates that inclusive settings do not negatively affect students without disabilities. Students without disabilities in inclusive classrooms typically show neutral academic outcomes, alongside social benefits such as increased peer interaction, collaboration, and acceptance of difference.6 These findings challenge the assumption that inclusive education undermines general education and instead suggest that well-supported inclusive classrooms can benefit a broad range of learners.

Inclusive education emphasizes both where students are educated and how educational environments are designed to support learning and belonging. In this sense, determining an individual student’s LRE is not simply a question of location. Studies that report mixed or weak outcomes for inclusive education often point to challenges in implementation, including insufficient professional learning, limited collaboration between general and special education staff, and misalignment between instructional expectations and available supports.7 This pattern is consistent with broader research on implementation of education policy, which shows that reforms are less effective when they are taken up superficially or symbolically rather than deeply embedded through coordinated instructional and organizational change over time.8 Inclusive education requires general education settings designed to serve learners through research-based instruction, collaborative structures, and personalized supports that ensure students’ access, dignity, participation, and learning.

Overall, the research suggests that the outcomes associated with inclusive education depend not simply on where students are placed but also on the quality of instruction, collaboration, and organizational supports they experience once there. Inclusive education matters because, when implemented intentionally, it supports access, belonging, and academic success for students with disabilities while strengthening learning environments for all students.9

The Supporting Innovative Practices Project

The Supporting Innovative Practices (SIP) project is funded by the California Legislature,10 administered by the Special Education Division of the California Department of Education (CDE), and operated through the Riverside County Office of Education (RCOE) and El Dorado County Office of Education (EDCOE). The project aims to help local educational agencies (LEAs) strengthen systematic implementation of inclusive education by transforming cultures, policies, and practices for students with disabilities.

LEAs—including school districts, charter schools, County Offices of Education (COEs), and special education local plan areas (SELPAs)—are identified to participate in SIP when statewide performance data collected as part of CDE’s Compliance and Improvement Monitoring (CIM) process indicate persistent, systemic patterns related to LRE that limit students’ access to general education. LEAs may also be referred from COEs and state partners when they express interest in strengthening inclusive practices. SIP currently includes 96 grantees who voluntarily participate and 10 assigned by the CDE Special Education Division (called “required” or “CIM” participants). Notably, nearly all required participants (98 percent over 10 years) ask to continue engagement with SIP as voluntary grantees once CIM support ends.

In partnership with lead agencies EDCOE and RCOE, the CDE reviews performance data and referrals to select each cohort within project staff capacity. Once they are invited to join the program, participating LEAs receive around $30,000 in one-time grant funding as well as multiyear technical assistance.

SIP’s goal is to increase the amount of time that students with disabilities spend in general education settings in California, as the state continues to lag national averages. Nationally, more than 67 percent of students with disabilities spend at least 80 percent of the school day in general education settings, compared with just over 60 percent in California.11 Staff from SIP lead agencies EDCOE and RCOE provide tiered technical assistance to build local capacity and support grantees with improving key performance indicators. Statewide data reported through EDCOE and RCOE and presented in this brief show consistent improvements in LRE indicators, reductions in restrictive placements, and shifts in educator beliefs across both voluntary and required SIP participants.

This brief presents evaluation evidence from SIP showing the project’s impact on adoption of inclusive practices, shifts in staff attitudes and beliefs, and indicators related to the amount of time that children with disabilities spend in general education. It concludes with insights from these efforts that may inform California’s continuous improvement agenda and future research.

LRE and Continuous Improvement in California

Students with disabilities make up nearly 14 percent of California’s K–12 student population, just below the national average of 15 percent.12 Even though California identifies a slightly smaller share of students with disabilities than the nation overall, the state places a smaller proportion of these students in general education settings for most of the school day. In 2024, 60 percent of students with disabilities in California were educated in general education classrooms for 80 percent or more of the day, compared with 67 percent (range of 53–82 percent) nationally.

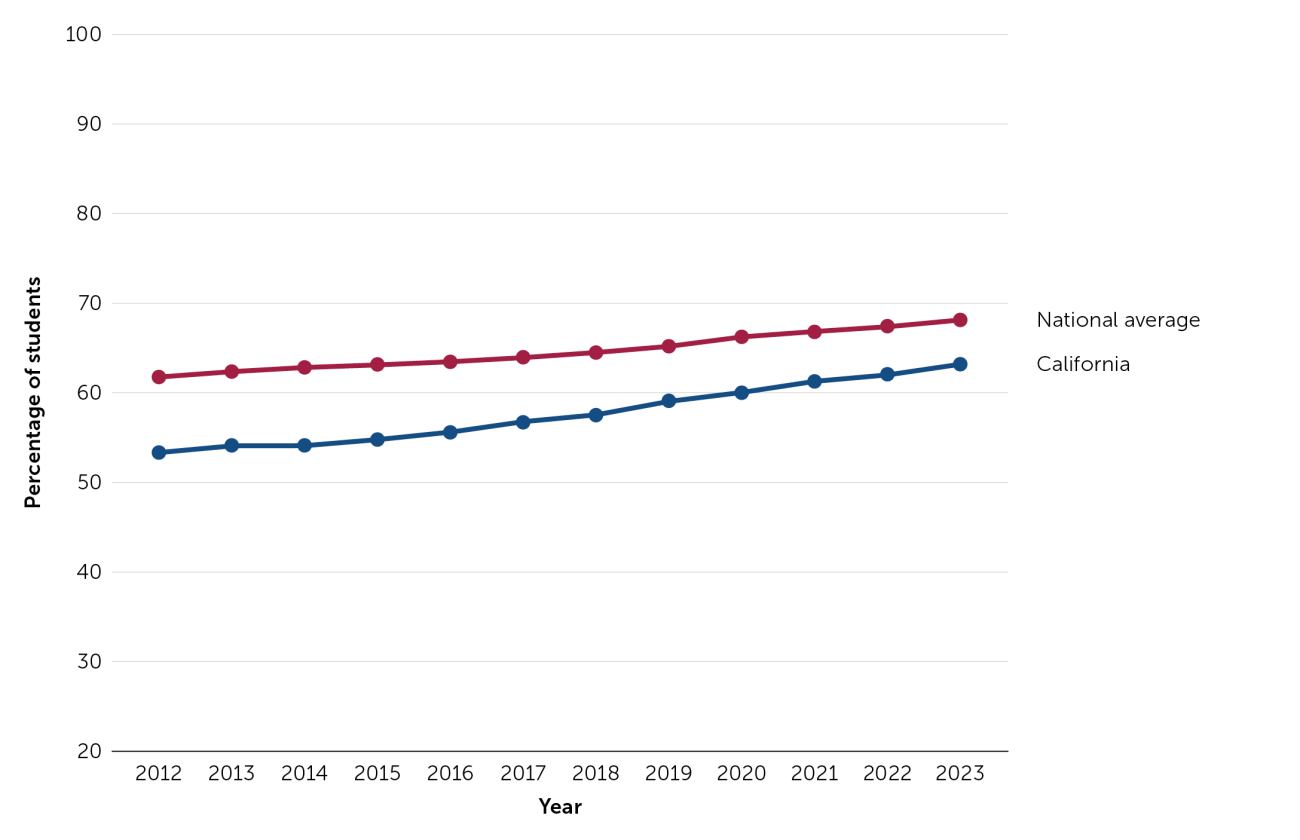

California’s rate of improvement on this indicator has also lagged national trends. Over the past 5 years, the national percentage of students with disabilities in general education 80 percent or more of the time increased by approximately four percentage points, while California’s growth over the same period was just over two percentage points. Figure 1 shows trends over time in the percentage of students ages 6–21 with disabilities who were educated in general education settings for 80 percent or more of the school day in California compared with the national average. Both California and the nation exhibit steady improvement over the past decade, but California consistently remains below the national average.

Figure 1. Percentage of Students With Disabilities Who Spent More Than 80 Percent of the Day in General Education Nationally and in California, 2012–23

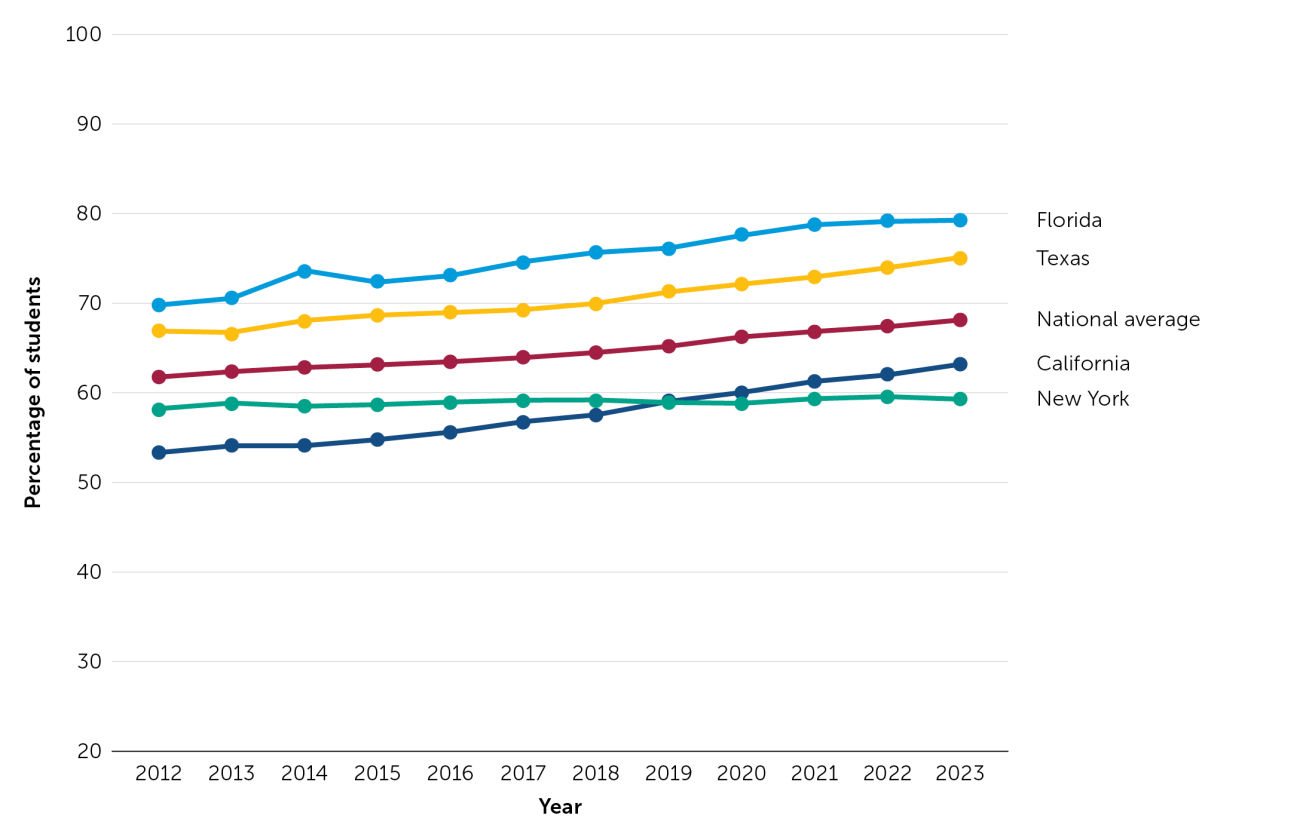

Figure 2 compares California’s trends to other large, diverse states—Texas, New York, and Florida—alongside the national average. While all four states demonstrate gradual improvement over time, California consistently reports lower rates of students with disabilities educated in general education settings for 80 percent or more of the school day. This comparison suggests that California’s lower rates may not be explained solely by the state’s scale or demographics.

Figure 2. Percentage of Students with Disabilities Who Spent More Than 80 Percent of the Day in General Education in California, Florida, New York, and Texas, 2012–23

Students with disabilities are consistently identified as a low-performing student group on the California School Dashboard and frequently overlap with other priority populations, positioning inclusive education as a critical lever for systemwide improvement within the state’s broader equity agenda. State policy frameworks—including the Multi-Tiered System of Supports, the Local Control Funding Formula, and the California School Dashboard—emphasize cross-department collaboration and shared accountability for outcomes across student groups, including students with disabilities.

Guidance from the CDE and the California State Board of Education reinforces this alignment by linking inclusive practices to educator capacity building, evidence-based improvement, and coordinated supports across programs within the California Statewide System of Support (SSOS).13 The state has made significant investments through the SSOS, a web of state-funded technical assistance initiatives and resource leads that develops resources and provides professional learning and strategic organizational consultation to support improvement efforts by districts and school sites.

SIP-Supported Districts Show Improvements in LRE and Conditions for Inclusive Education

This section presents findings on how SIP’s supports contribute to changes in educator learning, beliefs, and system-level outcomes related to time that students with disabilities spend in general education. Drawing on survey data, follow-up measures, and placement indicators, the findings examine how applied professional learning builds educators’ knowledge and early practice, how shifts in attitudes and beliefs begin to take hold with sustained engagement, and how these changes align with improvements in inclusive-placement patterns across SIP districts. Together, the results illustrate a pathway from applied learning to early implementation and measurable system outcomes.

The SIP Project Approach

SIP is designed to help districts move beyond compliance-oriented placement decisions towards coherent systems that support inclusive classrooms. To do so, SIP integrates support for cultural and organizational change, practice-based tools, and differentiated technical assistance.

SIP delivers support through a tiered system in which all LEAs have access to foundational resources (Tier 1), a cohort of voluntary grantees receives tailored technical assistance (Tier 2), and LEAs identified through CIM receive intensive, individualized support (Tier 3). SIP staff are geographically distributed across the state, allowing support to be responsive to regional contexts and district-specific conditions.

SIP’s work is guided by the Blueprint for Inclusion, a developmental roadmap that organizes district improvement efforts across sequential stages—from envisioning and building inclusive systems to implementing, scaling, and sustaining inclusive practice. The Blueprint helps leaders identify their current stage of development and follow clear steps to shape organizational culture and advance inclusive practices over time.

To operationalize this work, SIP articulates a set of Blueprint-aligned practices that define high-quality inclusive education as both placement in general education and the instructional, organizational, and cultural conditions that support student participation and learning. These practices are reinforced through applied professional learning offerings, leadership consultation, demonstration sites, self-assessment tools, and facilitated planning processes that support districts with translating vision into sustained practice.

Applied Learning: Building Knowledge and Early Practice

In response to grantee feedback requesting concrete examples of inclusive education in action, SIP developed Demonstration Sites and Inclusion Academies to support applied learning. SIP Demonstration Sites are LEAs that partner with SIP to pilot, refine, and model districtwide systems, policies, and practices that advance inclusive education for students with disabilities. SIP Inclusion Academies are structured, cohort-based professional learning experiences through which district and county teams build shared understanding, leadership capacity, and actionable strategies for implementing inclusive education as a systemwide improvement effort. SIP’s applied professional learning offerings are associated with meaningful short-term gains in educator knowledge and early adoption of inclusive practices.

During the 2024–25 pilot year, participants in SIP Demonstration Site visits (n = 450) showed statistically significant gains in knowledge of inclusive practices following a single site visit, with average scores increasing from 4.6 to 5.4 on a 6-point scale (p < .05). Participants also reported positive shifts in attitudes towards Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Similarly, participants in SIP Inclusion Academies demonstrated meaningful increases in knowledge—typically a half point to a full point on a 6-point scale—with the strongest growth in areas related to mindset, beliefs, action planning, and inclusive system design.

Follow-up surveys provide evidence that this learning translated into early changes in practice. Ninety days after participation, district teams reported applying what they learned by reviewing inclusion-related data, launching inclusion-focused workgroups, strengthening co-teaching structures, and incorporating inclusive practices into district improvement plans. Longer-term follow-up surveys administered 3–6 months after Demonstration Site participation showed statistically significant growth across multiple dimensions of inclusive practice, with average scores increasing from 3.7 to 4.1 on a six-point scale (p < .05).

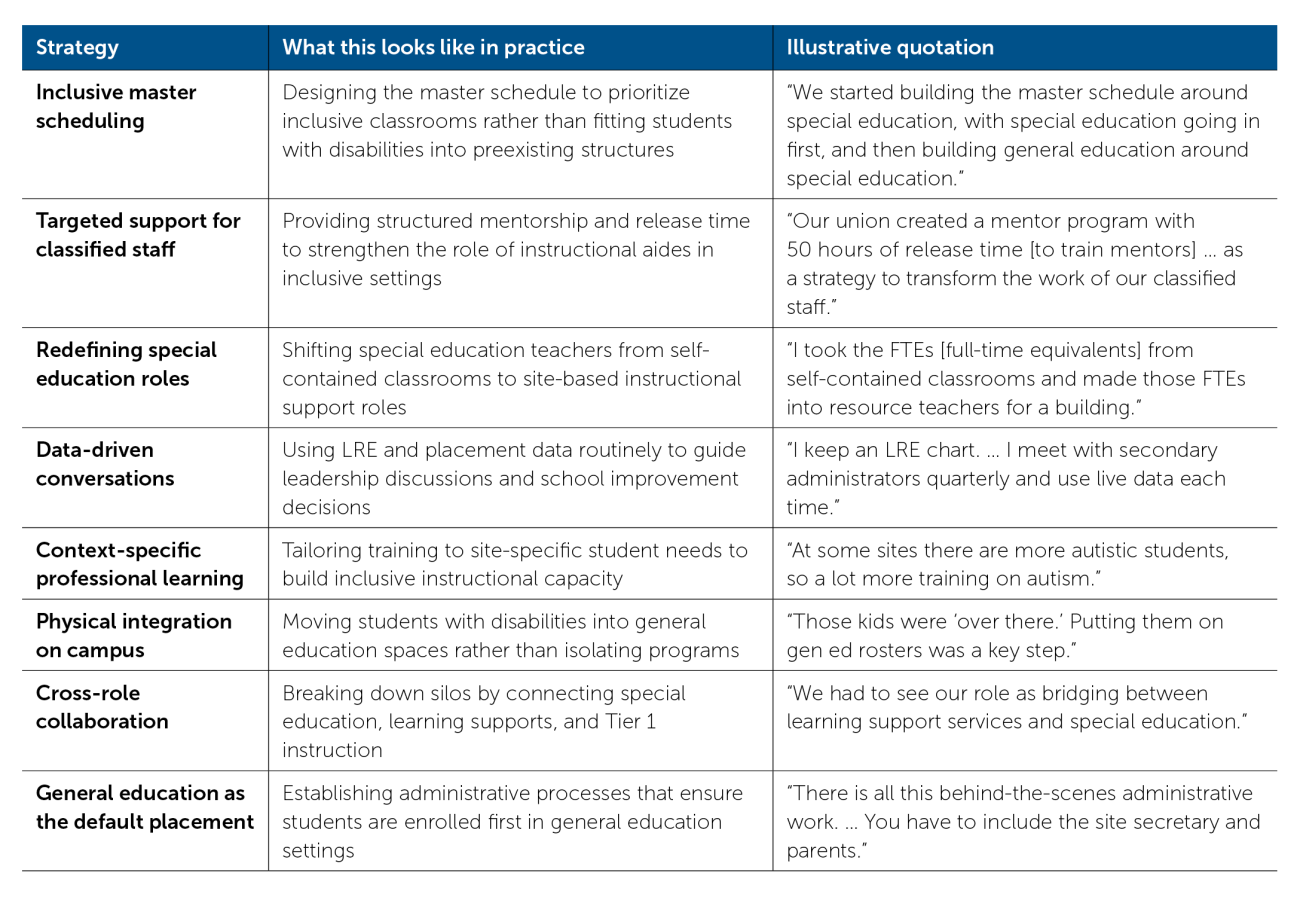

To illustrate how applied learning translates into early practice, Table 1 presents examples of concrete strategies for inclusive education reported by SIP participants. These examples highlight organizational and instructional changes that districts implemented as a result of SIP project engagement.

Table 1. Strategy in Action

Attitudes and Beliefs: Shifting Mindsets to Support Inclusive Education

As educators engage in applied learning and begin to implement inclusive practices, SIP also seeks to influence the beliefs and mindsets that shape whether those practices are sustained over time. SIP grantees consistently identify educator attitudes about disability and universal access as among the most significant barriers to inclusive education. Many general educators receive limited preparation related to special education—often a single course focused on legal compliance and eligibility rather than inclusive instruction—and may come to view disability as a category of need that requires separate settings and specialized expertise.14 Without sustained professional learning focused on inclusive practice, these beliefs can persist and undermine efforts to make general education environments more inclusive.15

Although shifts in beliefs associated with SIP participation are modest, they are consistently positive. Across the 2024–25 school year, educators in both voluntary and required SIP LEAs reported small but statistically significant increases in beliefs aligned with UDL, including attitudes related to student engagement, multiple means of action and expression, and representation. On a 14-item survey scale (maximum score of 18), average scores increased from 11.39 in the fall to 11.93 in the spring (p < .05). Although the magnitude of change is modest, the pattern suggests growing familiarity with and comfort using core principles of inclusive instruction.

Differences were more pronounced among educators whose districts engaged more frequently with SIP. Educators reporting three or more interactions per month with SIP staff had higher spring scores (12.4) than those reporting two or fewer monthly interactions (11.7; p < .05). District teams with more frequent participation in SIP coaching and technical assistance also reported slightly stronger ratings on measures of inclusive systems and organizational supports.

Taken together, these findings suggest that sustained engagement with SIP is associated with gradual shifts in educator beliefs and system-level conditions that support inclusive education. When combined with observed improvements in LRE indicators and reductions in restrictive placements, these early belief changes point towards strengthening local capacity to support more inclusive practices over time.

Placement and System Outcomes: Changes in LRE Data

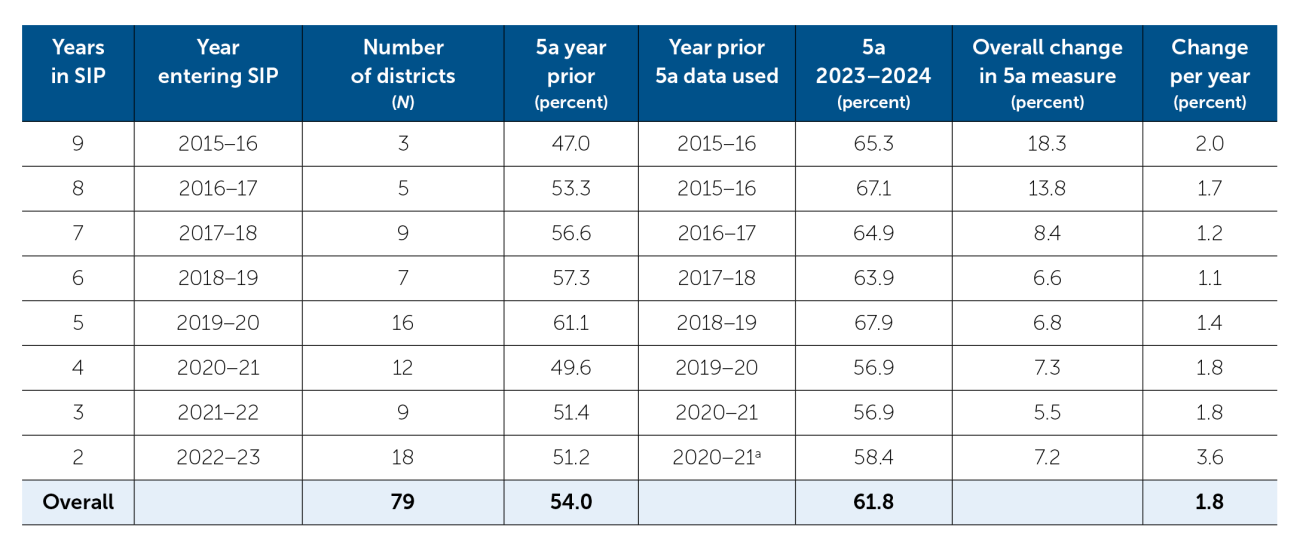

Changes in applied learning and educator beliefs provide important context for understanding observed shifts in placement patterns. Growth patterns in Indicator 5a (the percentage of students with disabilities served in general education for at least 80 percent of the day) on the IDEA’s annual performance report show that SIP grantees have improved at roughly double the state’s rate overall—or, in some cases, more than double (Table 2). For instance, the first SIP cohort’s 5a measure has increased by 18 percent since 2015, while the state increase in 5A was 6 percent and the national increase was 4 percent during the same timeframe.

Table 2. Cohort Analysis of SIP Districts

ᵃ Data for the 2021–22 school year are unavailable due to COVID-19–related disruptions in data collection and reporting.

For SIP grantees overall, the share of students served in general education for most of their day increased by an average of 1.8 percentage points per year, compared with less than 1 point statewide and 1 point nationally. Districts entering SIP with the lowest baseline rates made the largest gains, while higher baseline cohorts showed smaller but still positive gains. Over 5 years, SIP districts demonstrated 9 percentage points of growth, compared to 2 points statewide and 4 points nationally. That difference extrapolated for the state over 5 years would mean that 56,000 more students would be in general education settings for 80 percent or more of each school day.

SIP grantees also reduced the use of more restrictive placements. Across cohorts, use of separate schools (Indicator 5c) declined in six of seven cohorts, with reductions of up to 11.7 percentage points, and three cohorts met the state’s separate-school target of 2.6 percent or lower.

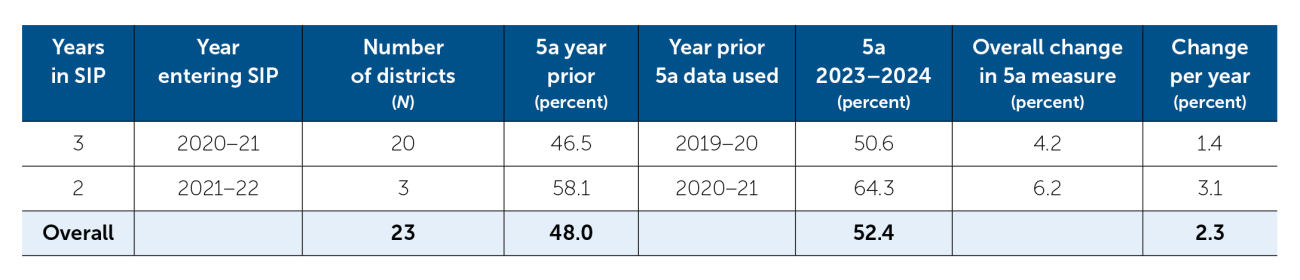

While some of the substantial increases in general education placements likely reflect the prior motivation and readiness of districts that voluntarily joined SIP, evidence also shows meaningful gains among LEAs that were required to participate through the state’s CIM process (Table 3). CIM districts—those entering the project because they did not meet special education annual performance indicator targets—achieved 4.16 percentage points of growth in Indicator 5a in the 2021–21 cohort and 6.20 points in the 2021–22 cohort. These positive trends indicate that improvement is feasible across varied levels of initial readiness and that SIP supports can catalyze progress even in districts that did not self-select into the project.

Table 3. Placement Change in CIM districts

Four District Strategies for Advancing Inclusive Education

The SIP project routinely examines what successful LEAs in California are doing to increase the time that children with disabilities spend in general education and improve the conditions for inclusive education. One such effort involved a series of case studies of four school districts that had significantly advanced their LRE indicators and implemented inclusive practices. Drawing on 24 interviews and a review of existing records, the team developed four in-depth case studies followed by a cross-case analysis.

Taken as a group, the cross-case findings reinforce what decades of school-improvement and system-change research have already shown: Sustainable change in educational organizations depends on a clearly articulated and widely shared vision,16 relational trust and strong social networks,17 and coherence between local routines and system goals.18 These elements are foundational for LEAs seeking to redesign teaching and learning at scale, and the four district case studies reflect these basic tenets. Although these are not novel concepts, it is important to acknowledge the degree to which inclusive education relies on the same system-change fundamentals that drive improvements in other areas of schooling.

Four district-level conditions emerged from the cross-case findings that reliably support improvements in inclusive placements and practices, in addition to reinforcing what we know about system change in schools. These conditions reflect how districts can translate technical assistance into meaningful, districtwide change.

Underlying Structures That Enable Inclusive Education

Districts that strengthened inclusive education invested in redesigning the structural components that determine how and where students with disabilities receive instruction—especially master schedules and strategic staffing. Administrators can design master schedules to prioritize inclusive classrooms by considering the placements of students with disabilities first rather than fitting them into preexisting structures. Strategic staffing could include shifting special education teachers from self-contained classrooms to site-based instructional support roles.

In evaluation data from both Demonstration Sites and Inclusion Academies, teams identified these structural redesigns as the clearest lever for increasing time in general education. These shifts enabled more effective co-teaching, clarified roles for paraeducators, and created more consistent instructional support within general education classrooms.

Leadership Mindset and Culture

Across surveys and site-visit reflections, leadership mindset was the most frequently cited factor shaping district readiness for inclusive education. Districts consistently reported that beliefs and culture—rather than resources—posed the greatest barrier to inclusive education. In districts where leaders reinforced shared responsibility for students with disabilities and cultivated trust and collaboration across roles, inclusive practices were more likely to take hold and be sustained. Exposure to strong models through Demonstration Sites and Inclusion Academies helped accelerate these mindset shifts by allowing school and district leaders to see inclusive classrooms functioning effectively in real settings.

Data-Driven Planning and Continuous Improvement

Effective districts used data not only to diagnose challenges but also to guide strategic planning and monitor implementation. Inclusion Academy teams, for example, were required to use local data to develop actionable plans for expanding access to general education. Follow-up surveys show districts applying these approaches when analyzing student access patterns. Several districts also emphasized the importance of routinely sharing special education student-level outcome data with district and site leaders outside of special education, using data as a tool to build shared understanding and accountability for inclusive practices. Districts that engaged in recurring data review were better able to refine their practices, adjust supports, and maintain momentum throughout the year.

Cross-Role Collaboration and Shared Leadership

Sustained improvement was evident in districts that built strong collaborative structures fostering coherence across general and special education, site and district leadership, SELPAs, and COEs. SIP’s multirole teaming model helped districts develop shared language, coordinate supports, and align improvement plans across levels of the organization. Follow-up surveys show many districts maintaining this cross-role structure to form inclusive education workgroups, expand co-teaching partnerships, strengthen professional learning, and embed inclusive practices within districtwide planning processes.

Policy Implications for California

Findings from the SIP evaluation point to several opportunities for state policymakers to strengthen and scale inclusive practices across California. While participating districts demonstrated meaningful progress when provided with targeted support, sustained and statewide improvement will require policy actions that reinforce the conditions that can advance inclusive education.

Strengthen Coherence and Shared Accountability Within the SSOS

Data from SIP indicate that cross-role and cross-agency collaboration is a foundational condition for inclusive education. State policy could support this work further by formalizing shared planning structures, common improvement tools, and joint accountability across SSOS partners—including COEs, SELPAs, the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, and the CDE. Clarifying roles, aligning technical assistance, and establishing shared expectations for inclusive practice within differentiated assistance and CIM supports would potentially reduce fragmentation and ensure that inclusive education is embedded within broader efforts to improve schools rather than treated as a separate initiative.

Expand and Institutionalize Inclusive Education Coaching

SIP evaluation findings indicate that seeing and personally trying out inclusive practices with support is the most effective way to change attitudes and sustainably integrate inclusive practices. This aligns with research showing that job-embedded, iterative coaching is far more effective than one-off workshops at changing educator practice because it provides sustained modeling, feedback, and opportunities for sensemaking within teachers’ daily work.19 While SIP already provides many coaching-aligned elements—such as guided reflection, repeated interactions with specialists, and structured planning—the program cannot directly coach every educator across the state. A promising next step is to support districts with developing internal inclusive education coaches. By investing in training and credentialing district-based coaches—spanning instruction, scheduling, service delivery, and leadership—the state could extend SIP’s reach, improve implementation fidelity, and ensure that inclusive practices are sustained beyond time-limited grants.

Establish Dedicated Categorical Funding Streams and Increase Resource Flexibility to Strengthen Inclusive Education

SIP districts consistently identified co-teaching, collaborative planning time, and shared professional learning as critical levers for expanding access to general education. Yet implementing these models at scale requires sustained investments in staffing, planning time, and professional learning—costs that districts often struggle to prioritize. Policymakers could create categorical funding specifically aimed at building and sustaining inclusive structures, such as support for inclusive education coaches, co-teachers, paraeducator training, or shared professional development for general and special educators. Targeted investments of this kind would directly resource the structural and instructional conditions that SIP districts identified as essential to improving inclusive practice and increasing the amount of time students with disabilities spend in general education. Importantly, greater flexibility in existing funding streams could allow districts to braid resources in ways that reinforce inclusive education rather than parallel general and special education systems.

Strengthen Teacher and Administrator Preparation for Inclusive Education

California’s “common trunk” teacher-preparation reforms represent a significant step forward in aligning teacher preparation with evidence-based, inclusive instructional practices. These reforms could be further bolstered by ensuring placement of student teachers in inclusive classrooms so that new teachers have tangible examples of what inclusive education looks like in practice. Also, existing reforms apply only to teacher preparation programs; they do not extend to the preparation or induction of school and district administrators, who are often the administrative designees on Individualized Education Program teams and responsible for implementing inclusive structures such as co-teaching, master scheduling, and cross-role collaboration. SIP findings demonstrate that leadership mindset and structural decision-making are among the strongest predictors of district progress in expanding access to general education. Updating administrator preparation and coaching to include competencies in inclusive scheduling, staffing redesign, collaborative teaming, and data-driven decision-making would bring leadership development into alignment with the common trunk reforms and provide districts with the leadership capacity necessary to sustain inclusive improvements over time.

Strengthen the Visibility of Inclusive Education Within California’s Accountability and Improvement Systems

SIP districts consistently reported that mindset and culture—not resources—were the greatest barriers to inclusive education, underscoring the importance of clear expectations and public transparency. Policymakers can reinforce inclusive practice by increasing the visibility of inclusion-related data within existing accountability and improvement systems. Specifically, the state could display Indicators 3, 5, 6, and 7 on the California School Dashboard to signal that inclusive placement is an essential component of education quality. Embedding inclusive education more explicitly into statewide accountability would normalize inclusive practice as a system expectation, not a discretionary initiative, and encourage earlier, proactive improvement rather than compliance-driven response.

Taken together, these policy implications underscore the importance of sustained capacity-building approaches to inclusive improvement. SIP findings suggest that the strongest and most durable gains occurred when districts engaged over multiple years, across multiple systems, and with consistent support that allowed time for learning, adaptation, and institutionalization. Policies that prioritize coherence, coaching, leadership development, flexible resourcing, and clear expectations are most likely to succeed when they are designed to support continuous improvement over time rather than when they are episodic interventions tied solely to compliance triggers—particularly for districts that serve high proportions of students with disabilities.

Research Implications

The SIP initiative offers promising evidence that targeted support can shift educator beliefs, strengthen district capacity, and expand access to general education for students with disabilities. At the same time, the findings point to several areas where additional research is needed to understand how inclusive education can be sustained and scaled across California’s diverse districts.

Strengthen Research Designs to Assess Impact

Because SIP grantees are not randomly assigned, evaluation findings cannot rule out selection effects or the influence of broader statewide trends on grantee outcomes. Future research should explore rigorous causal designs—including, where feasible, randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental approaches—to estimate SIP’s contribution to changes in LRE, educators’ beliefs, instructional practices, and students’ experiences. Mixed methods studies that pair quantitative comparisons with in-depth qualitative inquiry would also help identify the effects of SIP intervention and the mechanisms through which SIP supports can drive change. For example, research could compare the effects of Demonstration Sites, Inclusion Academies, and coaching-based technical assistance, as well as combinations of those activities, to determine which structures produce the strongest outcomes at scale.

Study if and How Districts Sustain Structural Changes Over Time

Research on inclusive education systems shows that structural changes, such as redesigned master schedules, persist only when bolstered by common beliefs and expectations as well as other policies that support integration, such as joint professional learning opportunities.20 SIP evaluation results indicate that districts frequently undertake structural redesigns, yet little is known about whether these changes are maintained once technical assistance ends. Longitudinal studies should examine how districts institutionalize or adapt structural shifts and identify the organizational conditions that support the long-term sustainability of inclusive routines.

Examine District Leadership for Inclusive Improvement

Although a substantial research base identifies the leadership competencies that principals need to advance inclusive school environments—including scheduling, strategic staffing, and collaborative culture building21—far less is known about the role of superintendents and school boards in sustaining inclusive education. SIP findings point to the importance of system-level decision-making in areas such as staffing models, scheduling expectations, resource allocation, and the integration of general and special education. Yet superintendent and school board leadership in these domains remains underexamined in the literature. Future research should investigate the district-level leadership routines, governance structures, and resource decisions that enable or constrain inclusive education across schools.

Develop Broader Measures of Inclusive Quality

LRE indicators measure access but do not capture the quality of instruction or the experiences of students in general education settings. High-quality inclusive education requires instructional and relational components that LRE alone cannot measure—such as the fidelity of co-teaching, the use of UDL to differentiate instruction, and students’ sense of belonging and engagement in general education classrooms. Developing and validating tools that assess instructional rigor, co-teaching quality, UDL implementation, and inclusive school climate would provide districts and the state with a more complete picture of how to measurably improve inclusive education. Such measures would also support continuous improvement by helping educators identify which aspects of inclusive education are working well and which require additional support.

- 1

Waitoller, F. R., & Kozleski, E. B. (2013). Working in boundary practices: Identity development and learning in partnerships for inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 31, 35–45. doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.11.006

- 2

Fuchs, D., Gilmour, A. F., & Wanzek, J. (2025). Reframing the most important special education policy debate in 50 years:How versus where to educate students with disabilities in America’s schools. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 58(4), 257–273. doi.org/10.1177/00222194251315196

- 3

Sailor, W., & Roger, B. (2005). Rethinking inclusion: Schoolwide applications. Phi Delta Kappan, 86(7), 503–509. doi.org/10.1177/003172170508600707

- 4

Jones, N., Kaler, L., Markham, J., Senese, J., & Winters, M. A. (2025). Service delivery models: Impacts for students with and without disabilities. Educational Researcher, 54(3), 141–152. doi.org/10.3102/0013189X251316269; Malhotra, K. P. (2024). Whose IDEA is this? An examination of the effectiveness of inclusive education. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 47(4), 1045–1070. doi.org/10.3102/01623737241257951

- 5

Cole, S. M., Murphy, H. R., Frisby, M. B., Grossi, T. A., & Bolte, H. R. (2020). The relationship of special education placement and student academic outcomes. The Journal of Special Education, 54(4), 217–227. doi.org/10.1177/0022466920925033; Fisher, M., & Meyer, L. H. (2002). Development and social competence after two years for students enrolled in inclusive and self-contained educational programs. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 27(3), 165–174. doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.27.3.165; Hehir, T., Grindall, T., Freeman, B., Lamoreau, R., Borquaye, Y., & Burke, S. (2016, August). A summary of the evidence on inclusive education (ED596134). ERIC. eric.ed.gov/?id=ED596134; Hughes, C., Cosgriff, J. C., Agran, M., & Washington, B. H. (2013). Student self-determination: A preliminary investigation of the role of participation in inclusive settings. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48(1), 3–17. doi.org/10.1177/215416471304800102; Shogren, K. A., Gross, J. M. S., Forber-Pratt, A. J., Francis, G. L., Satter, A. L., Blue-Banning, M., & Hill, C. (2015). The perspectives of students with and without disabilities on inclusive schools. Research and Practice for Persons With Severe Disabilities, 40(4), 243–260. doi.org/10.1177/1540796915583493

- 6

Kalambouka, A., Farrell, P., Dyson, A., & Kaplan, I. (2005, May). The impact of population inclusivity in schools on student outcomes. EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London. eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/PDF%20reviews%20and%20summaries/incl_rv3.pdf; Ruijs, N. M., & Peetsma, T. T. D. (2009). Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed. Educational Research Review, 4(2), 67–79. doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.02.002

- 7

Hehir et al., 2016; Ruijs & Peetsma, 2009.

- 8

Coburn, C. E. (2003). Rethinking scale: Moving beyond numbers to deep and lasting change. Educational Researcher, 32(6), 3–12. doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032006003

- 9

Fuchs et al., 2025.

- 10

Originally titled Supporting Inclusive Practices, the project was renamed Supporting Innovative Practices as it evolved to emphasize inclusive education as a core component of California’s broader continuous improvement and system-of-support framework. The SIP project was initially funded in 2015–16.

- 11

Office of Special Education Programs. (2024). IDEA Section 618 State Part B child count and educational environments. data.ed.gov/dataset/idea-section-618-lea-part-b-educational-environments/resources?resource=6be75820-f72a-42bf-8cb0-7016f21678e2

- 12

National Center for Education Statistics. (2024, May). Students with disabilities. nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg/students-with-disabilities

- 13

California Department of Education. (n.d.). Evidence-based school and classroom practices. www.cde.ca.gov/sp/se/sr/taskforce2015-evidence.asp; California Department of Education. (2019). California practitioners’ guide for educating English learners with disabilities. cde.ca.gov/sp/se/ac/documents/ab2785guide.pdf; Cal. Education Code § 52060. leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=EDC§ionNum=52060

- 14

Ruppar, A. L., Neeper, L. S., & Dalsen, J. (2016). Special education teachers’ perceptions of preparedness to teach students with severe disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41(4), 273–286. doi.org/10.1177/1540796916672843

- 15

Woulfin, S. L., & Jones, B. (2021). Special development: The nature, content, and structure of special education teachers’ professional learning opportunities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 100, 103277. doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103277

- 16

Fullan, M. (2016). The new meaning of educational change. Teachers College Press.

- 17

Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation. jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610440967

- 18

Coburn, C. E. (2003). Rethinking scale: Moving beyond numbers to deep and lasting change. Educational Researcher, 32(6), 3–12. doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032006003

- 19

Woulfin, S. L., Stevenson, I., & Lord, K. (2023). Making coaching matter: Leading continuous improvement in schools. Teachers College Press.

- 20

McLeskey, J., Spooner, F., Algozzine, B., & Waldron, N. L. (Eds.) (2014). Handbook of effective inclusive schools: Research and practice. Routledge; Sailor, W. (2014). Advances in schoolwide inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special Education, 36(2), 94–99. doi.org/10.1177/0741932514555021

- 21

Crockett, J. B. (2002). Special education’s role in preparing responsive leaders for inclusive schools. Remedial and Special Education, 23(3), 157–168. doi.org/10.1177/07419325020230030401; DeMatthews, D. E., Serafini, A., & Watson, T. N. (2020). Leading inclusive schools: Principal perceptions, practices, and challenges to meaningful change. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(1), 3–48. doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20913897; McLeskey et al., 2014; Waldron, N., McLeskey, J., & Redd, L. (2011). Setting the direction: The role of the principal in developing inclusive schools. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 24(2), 51–60. eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ963382

Ripma, T., & Wall, A. (2026, February). Advancing inclusive education in California schools: Lessons from the Supporting Innovative Practices Project [Practice brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/advancing-inclusive-education-california-schools