California’s Adoption of Reading Difficulties Risk Screening

Summary

Improving literacy outcomes for all children remains a key policy priority in California. Universal reading screening is an important step towards addressing persistent gaps and deliver equitable support for students who demonstrate reading difficulties. Following the passage of the 2023 Education Omnibus Budget Trailer Bill and codified by California Education Code § 53008, local educational agencies (LEAs) are required to administer universal screening for reading difficulties once per year in kindergarten through Grade 2. This policy brief responds to the mandate to adopt a reading difficulties risk screener by offering guidance to LEAs on the structures and processes needed to reduce implementation challenges. We then outline suggestions for local and state policymakers to build capacity and strengthen support to meet the infrastructural demands in districts across the state.

Introduction

Ensuring that all California students attain reading proficiency has increasingly become a policy priority for the state. Research has established how students learn to read and how those at risk for reading difficulties, including dyslexia, can be identified and supported.1 In response, California has taken steps to embed this evidence in policy by requiring public schools to adopt universal screening for reading difficulties in kindergarten through Grade 2.2 This statewide adoption gives local educational agencies (LEAs) funding and guidance to strengthen early identification and prevention of reading challenges. This brief outlines key considerations for implementing screening measures and for translating screening data into effective instructional support.

Key Ideas From California’s Policy on Universal Reading Difficulties Risk Screening

California’s adoption of universal reading difficulties risk screening advances literacy policy in California by mandating and funding early screening for all public school children in Grades K–2 by the 2025–26 school year. Specific highlights from the policy include:

- establishing the Reading Difficulties Risk Screener Selection Panel (RDRSSP) of experts to evaluate and vote to adopt a list of screening instruments for state approval using a review process approved by the State Board of Education (California Education Code § 53008(b));

- clarifying the definition, use, and research-based criteria of universal screeners for appropriate implementation in LEAs, including guidance for multilingual learners (MLLs), students receiving special education services, and exemptions;

- specifying universal screening as one aspect of a school’s overall approach to literacy instruction, assessment and data collection, intervention and support, and family communication;

- directing funding for LEAs as part of the Literacy Coaches and Reading Specialists Education Training (LCRSET) Grant through 2027 to develop literacy programs and interventions as well as to hire coaches and reading specialists;

- providing additional funding for LCRSET to a selected County Office of Education (COE) to develop training for literacy coaches and reading specialists; and

- allotting funding to support statewide implementation of evidence-based practices and curricula, data use, and professional development.

Together, these provisions mark a significant step towards aligning California’s literacy policy with research-based practices for identifying students in need of stronger early support for reading and providing evidence-based instruction and intervention.

Motivation for Universal Reading Difficulties Risk Screening in California

California’s adoption of universal reading difficulties risk screening reflects a policy response to persistent disparities in literacy achievement across populations in the state. These discrepancies necessitate the need for earlier, more equitable, and more effective interventions that are culturally and linguistically responsive and are tailored to the diversity across the state. The policy aligns with research showing that early identification and support are critical for preventing long-term reading difficulties. It is well documented that underdeveloped literacy skills affect academic potential, mental health, and overall life outcomes,3 yet reading difficulties are widespread.

Prevalence of Reading Difficulties

National and state data demonstrate the prevalence of students who do not meet grade-level literacy standards. Specifically, data in California indicate:4

- only 49 percent of all students met or exceeded proficiency in English language arts on the 2024–25 California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP);

- only 44 percent of all third graders and 15 percent of third graders identified as English learner (ELs) met or exceeded standards on the 2024–25 CAASPP; and

- despite marginal growth after the COVID-19 pandemic, California students’ scores remain below prepandemic levels.5

Reading difficulty is a broad term that may denote different conditions with different implications. Although universal screening targets only a risk for potential reading difficulties, advocates for children and families support screening as an important tool for identifying and tailoring proactive support for students who may be diagnosed with persistent word-reading disabilities like dyslexia. Diagnosed language-based learning disabilities are common and exist worldwide. Facts related to reading disabilities and dyslexia include the following:

- One in five children has a learning disability, and 34 percent of students receiving special education services in the United States are diagnosed with a specific learning disability related to reading, writing, and math.6

- Dyslexia, “a severe and persistent difficulty learning to read (and spell) words despite adequate opportunity and instruction”7 affects approximately 5–17 percent of children.8

- About 85 percent of children with a learning disability have difficulty with reading and language.9

Importance of Early Screening

Reading difficulties reflect diverse factors and experiences. While universal screening detects the risk of reading difficulties at large, it also serves as a tool for targeting risks for reading disabilities such as dyslexia, which often go undetected until third grade, when the window for prevention has passed and remediation becomes more challenging.10 Although evidence-based intervention and support benefit students across grades, intervention is more effective in earlier elementary, such as in first grade, when the brain’s structure is more malleable and responsive.11 Early remediation can also prevent more severe reading challenges as well as improve academic performance, mental health, and overall life outcomes. Furthermore, administering universal screenings to all students early in the school year helps identify those in need of targeted instructional support as soon as possible. The results not only guide differentiated instruction for individual students but also inform broader decisions about curriculum selection, staffing, resource allocation, and intervention planning across schools and districts.12

Considerations for Multilingual Learners

The California system of public education serves the largest multilingual student population in the nation, with nearly 20 percent of public school students classified as ELs.13 Research shows that MLLs develop literacy along trajectories in each of their languages that differ from their monolingual peers. Language exposure and proficiency in each language must be considered along with the language of instruction when developing screeners. To address this, the universal reading difficulties risk screening policy includes provisions for screening MLLs so that assessments more accurately capture the academic, cultural, and linguistic profiles of students, particularly native Spanish speakers.14 Screeners that are appropriate for MLLs require careful implementation and interpretation, with attention to how language development interacts with reading ability to ensure accurate identification and support.

From Policy to Practice: How Universal Screening Works in Schools

As the first step in the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS), universal screening initiates a systematic progression of assessment tools, data interpretation, and delivery of targeted instruction and intervention.15

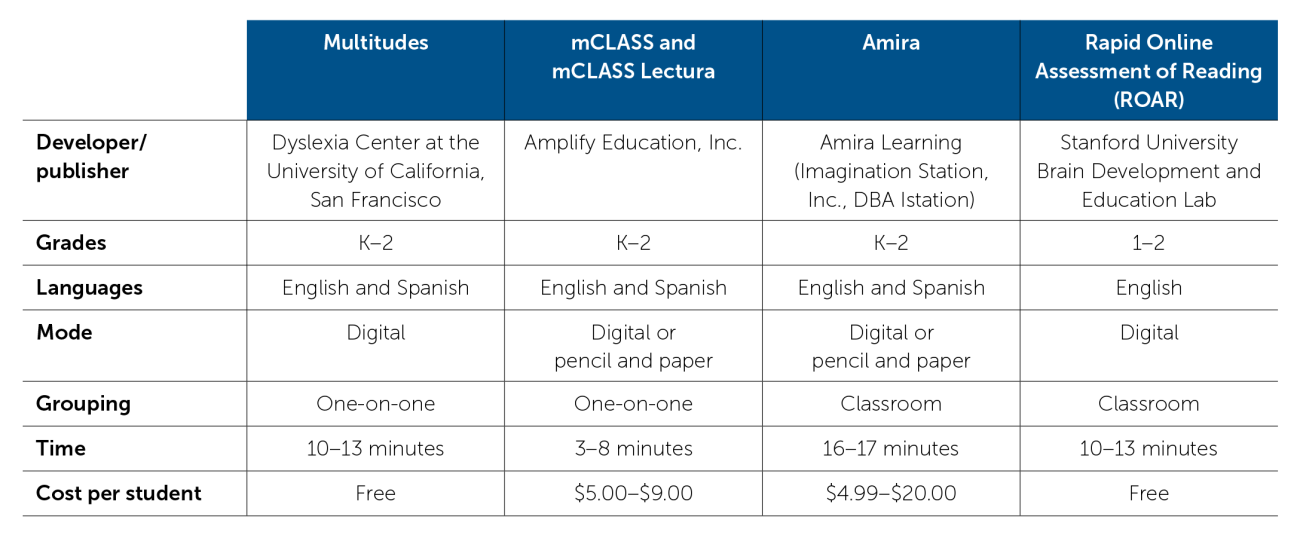

In December 2024, following a lengthy public review process, the RDRSSP approved four instruments (see Table 1) according to a detailed rubric approved by the State Board of Education. In its evaluation criteria, the RDRSSP emphasized the need for the approved tools to have been developed using data from a population representative of Californian primary school students as well as the possibility of screening in languages other than English.16 These screeners were approved because the panel found them to (a) have sufficiently sound psychometric properties, (b) be brief and simple to administer, and (c) be easily usable by educators. Although the four instruments have many similarities, such as the skills they assess and their availability through a digital interface, there are some key differences to note: (a) grades and languages for which the screener was approved, (b) time required for administration, (c) setting of administration (i.e., individual vs. whole class), and (d) cost per student. By this time, most districts or schools will have already chosen one or more preferred screening tools.

Table 1. Key Characteristics of the Four State-Approved Universal Reading Screeners

Note. Mode, grouping, and time refer to the universal screening component; differences in mode, grouping, and time exist for recommended additional or follow-up measures. All information is from the information overview on the California Department of Education’s website.

Communicate screening logistics to teachers and families at the beginning of the school year

The bill requires schools to notify families at least 15 school days before commencing screening. The communication must be available in multiple languages spoken in the community, name the chosen screening instrument, explain the reasoning behind its selection, and mention the implications of screening on children’s educational experiences. This must include criteria and instructions for student exemption (e.g., ongoing or completed evaluation for reading difficulty, diagnosis, or special education eligibility).17

Administer screeners to all (nonexempt) students at the beginning of the school year

Schools are required to administer the universal screening to all K–2 students once: at the beginning of the school year or within 45 days of a new student entering the school. For screeners requiring one-on-one administration, schools may either have substitute teachers cover while classroom teachers carry out the screening or use designated reading specialists, instructional coaches, or other trained paraprofessionals (e.g., because of capacity or availability of resources) to screen students. Schools should account for space, noise, and access, so planning for additional areas for individual administration and availability of computers and headphones for digital assessments should be considered.

Whenever possible, literacy screeners—particularly those parts assessing language skills—should be administered in both the language of instruction and the student’s home language(s), as reported by their parents upon initial enrollment. This allows educators to distinguish between difficulties rooted in English language acquisition (which may present only in English) and those stemming from underlying reading challenges (which typically appear across languages). Best practice is for screeners to be administered by an assessor fluent in the language of the test to ensure accurate pronunciation, student comfort, and valid results.18

Communicate screening results and next steps (e.g., assessments and follow-up instruction) for all students

Schools must provide screening results within 45 school days of administration. These reports should be clear about what an “at risk” result means and explain in accessible language which skills were assessed as well as, if applicable, which benchmarks or normative comparisons were used. It is important to stress that universal screening results are not diagnostic. Rather, they are designed to provide a brief overview of whether a student is meeting expectations for foundational reading skills and is on track to learn to read well. Schools should also report additional considerations and qualifications of the results for MLLs and outline next steps, including planned or recommended follow-up assessments, progress monitoring, planned strategies for grade-level instruction at school, and resources for families to promote literacy development.19

Conduct follow-up assessments and progress monitoring that align with evidence-based instruction and intervention

Educators should continue to implement evidence-based Tier 1 (whole-class) literacy instruction that comprehensively addresses the multicomponent skills of reading and adjusts methods for intervention and support that align with the needs of students identified with reading difficulties. Follow-up diagnostic assessments should be administered to children flagged as “at risk” to identify specific areas where they need more support or intervention. Continued progress monitoring tracks whether a child is making progress because of the targeted intervention.20 Evidence-based targeted intervention is explicit, structured, and systematic and provides students at risk with repetition, practice, and feedback on reading skills. It can occur in small groups or one-on-one.21 Ongoing progress monitoring may also inform whether children need more intensive intervention or whether a referral for evaluation is warranted.22

Considerations for Using and Interpreting Results of Universal Reading Difficulties Risk Screening

In this section, we present some considerations to help educators (a) make sense of the screener results and (b) interpret and use them in a fair and valid way. Most importantly, educators should be aware of what an “at risk” designation means and what it does not mean.

What does an “at risk” screening result mean?

Universal screeners predict risk of developing reading difficulties; they do not diagnose disabilities.

Generally, screeners are designed to predict students’ risk of developing a general reading difficulty, not to identify specific underlying disabilities. While the legislation requires screening for “risk of reading difficulties [which is defined as] a barrier that impacts a pupil’s ability to learn to read or improve reading abilities, including dyslexia,”23 the specific way in which reading difficulty is measured differs from one screener to another. Therefore, educators should be familiar with the documentation of their chosen screener in order to draw appropriate conclusions and plan next steps. Broadly speaking, when a child is identified as “at risk,” it signals that the student may struggle to develop foundational literacy skills without additional support. This classification is an indicator—not a diagnosis—and it highlights the need for closer monitoring, further assessment, and if appropriate, timely intervention.

What does universal screening capture and what does it miss?

Results are binary or categorical indicators, which need to be interpreted alongside contextual information.

Reading is complex and multifaceted, and it requires several underlying foundational skills,24 spanning both language and literacy abilities, as well as broader cognitive functions. The skills best suited for screening also change quickly across K–2, reflecting the rapid development in language and literacy that children undergo at this age. This requires different skills to be assessed in the different grade levels.25 Therefore, acknowledging the complexity of reading, the policy specifically requires the RDRSSP to consider the following domains when making decisions about screeners:

- oral language,

- phonological and phonemic awareness,

- decoding skills,

- knowledge of letter names and letter sounds,

- rapid automatized naming,

- visual attention,

- reading fluency,

- vocabulary, and

- language comprehension.

Understandably, for practical and logistical reasons, none of the approved screeners taps into all these domains as part of its universal screening protocol (though many have tests of these domains as part of their overall offerings). Therefore, universal screening often yields binary results (e.g., risk/no risk), sometimes accompanied by percentile ranks or other norms. These results are obtained by comparing a student’s performance to established benchmarks or probability thresholds. Although this is very useful as a first indicator, it is important to consider students’ performance on other foundational reading skills as well as contextual information to get a fuller picture of their skills and reduce the number of false positive results. Therefore, it is beneficial to supplement the results from universal screening with domain-specific ability measures to understand students’ strengths and needs in reading comprehensively as well as to inform targeted instruction.26

How “accurate” are universal screeners?

They tend to overidentify students as “at risk” to make sure no child who truly needs support is missed.

Screeners rely on a limited set of tasks—sometimes even a single highly predictive indicator of later reading outcomes. While this efficiency allows screening to be conducted widely and quickly, it comes at the cost of nuance. As such, universal screeners are designed to flag all students in need of additional monitoring and support, not to provide diagnostic information about the specific causes of difficulty.27 Consequently, screeners tend to prioritize sensitivity—correctly detecting children who really are at risk—over specificity—correctly avoiding the overidentification of children who are not at risk. Because the purpose of universal screening is to identify all students who may be at risk for reading difficulties as early as possible, some degree of overidentification is an expected outcome—that is, some children flagged as “at risk” will later be found not to require additional intervention.

Do universal screeners work equally well for MLLs?

They yield fair and informative outcomes only when developed and normed with a representative sample.

Many screening tools were originally developed and normed on monolingual English speakers.28 Tasks designed without attention to linguistic diversity often fail to capture the constructs they intend to measure when administered to students from other language backgrounds.29 And if MLLs are compared to norms derived from samples comprising only monolingual English speakers, the results may be misleading.30 Bias can also arise from cultural differences, varying levels of English exposure, and unequal access to preliteracy experiences,31 all of which affect the validity of screening results. Moreover, reading difficulties may appear differently across languages. Therefore, two groups must be distinguished: students with underlying neurodevelopmental conditions, such as dyslexia, which affect reading across languages; and students struggling to read specifically in English. The latter group may perform poorly due to limited English exposure rather than a disability, hence requiring interventions geared at helping them improve their overall English language skills as opposed to those targeting specific cognitive skills.32

California’s screener-approval process sought to address the risk of misidentification that arises when MLLs are compared against benchmarks normed only on monolingual English speakers. The RDRSSP required that all approved screeners demonstrate reliability and validity evidence for the use of their instrument with MLLs, including evidence from diverse norming samples and subgroup analyses. This makes California’s set of approved tools stronger for the diversity of California’s students than many used nationally. Nevertheless, practitioners should remain attentive to the difference between challenges with English language acquisition versus reading difficulty for MLLs, using screening results as one piece of evidence, not a stand-alone diagnosis. Students’ language exposure, cultural background, and access to literacy experiences should be considered when interpreting results.

Lessons From Universal Screening Efforts in Other States

California is not the first state to adopt early reading screenings; rather, it joins a growing wave of states responding to a strong body of research showing that early, universal screening can help mitigate the risk of later reading difficulties and enable timely support for students, including those who may ultimately be diagnosed with disabilities like dyslexia. This policy direction reflects a growing national consensus that preventing reading difficulties early is far more effective and efficient than remediating them later.33 As lessons from the wave of reading legislation across the country emerge, one common challenge has been the implementation needs that arise from reforms in how schools approach screening, identification, curriculum, and professional development.34 Research has highlighted several barriers that can hinder effective implementation of universal screening requirements, including:35

- time burdens for administering screeners, which reduce instructional time and may require substitute coverage;

- technical expertise demands, particularly for administering assessments accurately to MLLs;

- sustained professional development needs to ensure that educators can implement, score, and interpret screeners effectively;

- locating and training staff to administer assessments in languages other than English; and

- challenges associated with integrating screening results into existing instruction, intervention, and support systems.

Given the diversity of California’s education system and the prioritization of local control, implementation of statewide policies may not follow a single model. Nevertheless, these findings underscore two interrelated priorities for California: (a) district leaders must design and adapt district structures and processes to anticipate and minimize implementation challenges; and (b) policymakers at both the regional and the state levels must invest in capacity building and provide the support necessary to meet the infrastructural demands of those charged with enacting new policies. District leaders can use the following lessons from universal screening efforts in other states to assess current progress of implementation and expand coordination of district structures to mitigate potential challenges.

Lesson 1: Identify a central team to lead screening administration

Lessons from research conducted across states show that scaling universal screening effectively districtwide requires dedicated technical expertise and coordination.36 This can be achieved either by creating a new district-level team focused specifically on screener implementation or by broadening the scope of an existing team, such as one focused on literacy or assessment, to take responsibility for screener implementation.37 A strong team would demonstrate three domains of expertise: (a) robust knowledge of literacy development, instruction, and intervention;38 (b) culturally and linguistically responsive and equitable screening practices; and (c) strategic planning and systems expertise.39

To transform policy into action, the team would first evaluate existing district infrastructure and processes to support literacy (e.g., assessment, data, instruction, intervention, and professional development) using systematic tools like California’s Local Literacy Planning Toolkit. Then, the team would provide technical oversight to select and integrate new screening measures into existing systems and align ongoing professional development.40 A key role of this central team could be identifying ways to ease the capacity strain that often comes with introducing new assessments. One way to build capacity is to direct the responsibilities of instructional coaches and reading specialists for leading screening processes. Specialists could also add value to a schoolwide team, especially in coordinating screening, interpretation, and professional development support.41

In cases where schools face continued capacity or funding challenges, a central team could provide coaching and guidance to teachers who may need to administer screening in classrooms. Districts can think creatively about staffing for screening, involving paraprofessionals or school-based tutors with adequate training and support as part of the administration process.42 An additional option could involve partnering with nearby teacher-preparation programs where teacher candidates administer screening as part of a practicum experience.

Lesson 2: Prioritize targeted, strategic, and ongoing professional development for educators

Both research-based recommendations and early implementation studies converge on a central priority: Sustained professional development is critical to the success of universal screening policies.43 Educators encounter a high volume of offerings from external providers alongside state-sponsored options with varying modes of delivery and opportunities for interaction and sustained engagement. While this abundance reflects a diversity of options, it also means that individual teachers need to navigate, organize, and participate in these opportunities amid competing daily demands. To be more effective, professional learning must move beyond ad hoc participation and be strategically planned, coherent with curriculum and instruction, and directly connected to classroom practice. Yet schools often fall short on creating the conditions necessary for systematically designed teacher learning. District leaders must create the time and conditions to sustain teacher learning and coherent school improvement.44 Lack of adequate training risks reducing screening fidelity, such as potential scoring errors that compromise accuracy of identification, misinterpretation of screening results, or inappropriate use of data to guide instruction and intervention using available curricula and programs.45

Even as schools and districts balance multiple initiatives, it is timely and critical for leaders to prioritize districtwide professional development with structured, ongoing training for designated staff during the initial rollout and follow up. This may first involve strategic leadership from the superintendent and school board as well as partnership with the local teacher’s union to proactively cultivate buy-in. Effective professional development is targeted, strategically planned, and ongoing, and it reflects the following key pillars46 that schools can use to tailor it for universal screening and follow-up instructional support.

- Targeted focus: Professional development should teach educators about (a) reading development and the multicomponent skills and knowledge (word reading, oral language, content knowledge, writing) that underlie it; (b) characteristics of reading difficulties like dyslexia; (c) how to approach screening MLLs; (d) the purpose and process of administering universal screening; (e) how to differentiate screening from diagnostic assessments and progress monitoring; (f) interpretation of results across populations; and (g) data-based decision-making for instruction and intervention.

- Ongoing, varied opportunities for professional development: Effective professional development integrates presentation of content, examples of effective models, active practice and collaboration, and instructional coaching. Since many schools may face challenges with time constraints and capacity, professional development may include asynchronous offerings on reading and screening, such as free modules developed by the UC|CSU Collaborative for Neuroscience, Diversity, and Learning; webinars offered by the California Department of Education, county offices, or other organizations offering research-based information. These asynchronous learning tools ideally would be followed by a model demonstration of screening a student, a practice session, and coaching. For schools with limited professional development time, it is important to prioritize live, active, hands-on learning.

- Extended learning with reviewed resources: A 2024 study conducted by the Science of Reading Center at State University of New York at New Paltz indicated that many teachers seek information about reading from a variety of external sources outside their structured professional development.47 Schools that support volunteer professional development or have funds for teachers to pursue learning could provide stipends for teacher leaders to curate websites of reviewed, context-specific resources for other teachers in the school or district community.48

Lesson 3: Evaluate and strengthen the coherence of existing MTSS that involve in-depth assessments, literacy instruction, and intervention

To achieve its intended outcomes, universal screening must be embedded in a coherent, well-aligned MTSS, with frequent data collection, strong instructional practices, structured interventions, and reliable systems for using data-based decision-making. Recent survey research showed that schools that have stronger existing MTSS were more effective in integrating the screening measures.49 Guidance from both research and other states recommends not just robust annual screenings but ongoing, frequent assessment, data collection, and analysis. For example, Massachusetts guides schools to conduct benchmark assessments at the beginning and middle of the year, with regular progress monitoring that aligns with both Tier 1 instruction and Tier 2 and 3 interventions to students showing risk.50 Other research supports administration of screening in two phases to reduce potential mistakes (e.g., from human or screener error), where everyone is screened initially, followed by a second measure for students who demonstrate risk. Students who continue to show difficulties then receive intervention with progress monitoring to track whether they are responding to continued support and intervention.51

Universal screening must exist concurrently with high-quality, multicomponent reading instruction.52 Equally important, schools need to strengthen their systematic approaches for students who need continued Tier 2 and 3 interventions. A multicomponent, structured approach to core reading instruction and intervention that includes phonics has continuously been shown to be effective. Strategies like higher dosage, repetition of skills, explicit instruction, and smaller group size have all been shown to support students who continue to need intervention.53

Finally, schools need to reinforce systems with standardized processes and protocols for storing, interpreting, sharing, and using data to make informed decisions about students. Strengthening existing systems of support is certainly complex as schools and districts target administration of universal screening, coordination of decision-making, and communication across the various channels. But coherence and alignment of systems are nevertheless critical to ensuring that a new mandate achieves the promised outcomes for all students.54

What Can the State Do to Support Universal Screening Implementation and Continuous Improvement?

As the state continues to commit to literacy initiatives and reform, universal literacy screeners will play a pivotal role in advancing statewide literacy goals. Yet disparities in district capacity threaten consistent implementation. The state must step in to provide infrastructure, training, and technical support while building systems to evaluate and continuously improve screener use across contexts to ensure that screeners become an equitable, effective tool for informing instruction and intervention as well as for strengthening literacy outcomes statewide.

Address disparities in infrastructure and capacity across districts

While accounting for balancing the Local Control Funding Formula’s emphasis on local agency and ownership of decision-making, some centralization of resources for screening administration and professional development can be appropriate to ensure that equitable guidance is disseminated statewide. Even when funding is allocated, districts may struggle with coordinating the administration and interpretation of screeners, particularly when it comes to designating sufficient internal capacity to manage the process. Analysis of screening-policy implementation from other states shows a variation in school contexts across socioeconomic status.55 In cases where schools face significant capacity challenges, public infrastructure from COEs and the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, networked communities, or partnerships with external providers may be needed for proactive reinforcement of technical leadership and expertise.

The California Statewide System of Support offers various professional development opportunities for counties and schools. More importantly, schools would benefit from systematic, sequential approaches to teacher learning to facilitate a cohesive and coordinated statewide effort to promote literacy outcomes. Instructional coaching, for example, is an area that warrants increased statewide coordination and guidance. Instructional coaching is an effective method of professional development, as documented by professional development frameworks and causal research studies. Yet despite its promise, coaching can yield variable effects across individual coaches and programs, especially at scale, because of disparate factors like individual coaching effectiveness, coaching expectations and time spent, training, and environmental and contextual factors.56 In addressing this variability, other states have invested resources towards increasing the fidelity and quality of coaching. For example, Mississippi has developed clear expectations of coaches and their relationships with school partners.57 Increased coordinated guidance and training must adequately support implementation to meet expectations and maximize continued investments (e.g., financial, human resources, infrastructure) in coaching as specified in the LCRSET Grant.

Invest in continuous evaluation and alignment of screeners

Results from universal literacy screening will offer valuable insights into how the system is effectively promoting literacy for all children; however, the policy does not establish mechanisms for the state to gather lessons from the implementation of universal screeners, monitor effectiveness across diverse contexts, or adjust strategies over time, representing a missed opportunity for continuous improvement. Given the steep investment that the state has made in literacy through the universal screening statute, it is vital to establish a systematic, central approach to data collection and analysis. Data analysis of specific screeners would assess the outcomes, understand each screener’s validity and reliability for the populations that California serves, and refine benchmarking. In addition to collecting screening data, the state can partner with researchers to replicate existing studies that evaluate the implementation of screening policies and practices58 in order to better understand overall quality and fidelity, potential disparities and unintended consequences, and barriers and facilitators within local contexts. Another way to understand screening within the broader data system would be to connect results from screeners to other cohort-based measures like statewide Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium results and Individualized Education Program status (categorized across subsets of the population) to track overall literacy performance and assess rates of identification and support. Systematic and continuous evaluation will enable the state to track the effectiveness and accuracy of assessments, which will require investments appropriate to the tools and resources themselves.

Conclusion

California’s policy requirement that all districts adopt a literacy screener and annually screen all students in kindergarten through second grade is an important step that promises to improve literacy outcomes for many students. To achieve this goal, districts need to administer screeners well and effectively interpret them across populations as well as use the data to plan instruction and intervention. This will require substantial time for leading the initial implementation and scaling the initiative across California’s diverse classrooms. Both educators and families will need to develop an understanding of the screeners. Programmatically, reading instruction will need to be reviewed broadly and potentially revised to ensure that students who are struggling do receive the help they need as part of Tier 1 instruction or through additional targeted support. With all the other requirements that districts face as well as the knowledge and skills needed for strong implementation, it will be important to document and follow how districts implement screener requirements. This data collection will allow the state to track how districts use the resources allocated and whether better reading outcomes across the state are achieved.

Given the extent and significance of the investment in both time and money, the stakes are high. California would be well served to dedicate resources to a rigorous evaluation. Systematic, timely data collection could help identify best practices and recommend improvements during the initial years of implementation as well as assess outcomes for districts to continue to build their capacity.

Note: The California County Superintendents Curricular and Improvement Support Committee (CISC) has provided a Reading Difficulties Risk Screener Adoption Toolkit.

- 1

Gotlieb, R., Rhinehart, L., & Wolf, M. (2022). The “reading brain” is taught, not born: Evidence from the evolving neuroscience of reading for teachers and society. The Reading League Journal, 3(3), 11–17. thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/ The-Reading-Brain.pdf; Petscher, Y., Cabell, S. Q., Catts, H. W., Compton, D. L., Foorman, B. R., et al. (2020). How the science of reading informs 21st-century education. Reading Research Quarterly, 55 (1), S267–S282. doi.org/10.1002/rrq.35

- 2

Education Omnibus Budget Trailer Bill, S. Bill 114, Chapter 48 (Cal. Stat. 2023); Cal. Education Code § 53008.

- 3

Gaab, N. & Petscher, Y. (2022). Screening for early literacy milestones and reading disabilities: The why, when, whom, how, and where. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 48(1), 11–18. onlinedigeditions.com/article/Screening+for+Early+Literacy+ Milestones+and+Reading+Disabilities/4226252/740141/article.html; Ozernov-Palchik, O., & Gaab, N. (2016). Tackling the ‘dyslexia paradox’: Reading brain and behavior for early markers of developmental dyslexia. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 7(2), 156–176. doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1383

- 4

California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress. (n.d.). Test results for California’s assessments. caaspp-elpac.ets.org

- 5

Gallagher, H. A. (2025, January 22). Modest gains and persistent gaps in student performance in 2023–24 [Commentary]. Policy Analysis for California Education. edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/modest-gains-and-persistent-gaps-student-performance-2023-24

- 6

National Center for Learning Disabilities (2025, April 10). California state snapshot of specific learning disabilities. ncld.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Snapshot-SoLD-06102023-web_ca.pdf

- 7

Catts, H. W., & Petscher, Y. (2021). A cumulative risk and resilience model of dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 55(3), 171–184. doi.org/10.1177/00222194211037062

- 8

Ozernov-Palchik & Gaab, 2016.

- 9

International Dyslexia Association. (2020). Dyslexia basics. dyslexiaida.org/dyslexia-basics

- 10

Catts, H. W., & Hogan, T. P. (2020, August 22). Dyslexia: An ounce of prevention is better than a pound of diagnosis and treatment. doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/nvgje; Ozernov-Palchik & Gaab, 2016.

- 11

Solari, E., Hall, C., & McGinty, A. (2021). Brick by brick: A series of landmark studies pointing to the importance of early reading intervention. The Reading League Journal, 2(1), 18–21. thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/TRLJ-Jan-2021-Article-Sneak-Peek.pdf; Wanzek, J., & Vaughn, S. (2007). Research-based implications from extensive early reading Interventions. School Psychology Review, 36(4), 541–561. doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2007.12087917

- 12

Ozernov-Palchik & Gaab, 2016.

- 13

California Department of Education. (2024–25). English learners by grade & language. dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/DQCensus/EnrELAS.aspx?cds=00&agglevel=State&year=2024-25

- 14

Goodrich, J. M., Fitton, L., Chan, J., & Davis, C. J. (2022). Assessing oral language when screening multilingual children for learning disabilities in reading. Intervention in School and Clinic, 58(3), 164–172. doi.org/10.1177/10534512221081264

- 15

McIntosh, K., & Goodman, S. (2016). Integrated multi-tiered systems of support: Blending RTI and PBIS. Guilford Press.

- 16

California Department of Education. (2025). Reading difficulties risk screener selection panel. cde.ca.gov/be/cc/rd

- 17

Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, 2023.

- 18

Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, 2023.

- 19

Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, 2023.

- 20

Catts, H. W., Nielsen, D. C., Bridges, M. S., Liu, Y. S., & Bontempo, D. E. (2013). Early identification of reading disabilities within an RTI framework. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(3), 281–297. doi.org/10.1177/0022219413498115

- 21

Gaab & Petscher, 2022; Miciak, J., & Fletcher, J. M. (2020). The critical role of instructional response for identifying dyslexia and other learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 343–353. doi.org/10.1177/0022219420906801; U.S. Department of Education. (2009, February). Assisting students struggling with reading: Response to Intervention (RtI) and multi-tier intervention in the primary grades. (NCEE 2009-4045). Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/docs/practiceguide/rti_reading_pg_021809.pdf

- 22

Al Otaiba, S. A., Kim, Y.-S., Wanzek, J., Petscher, Y., & Wagner, R. K. (2014). Long-term effects of first grade multitier intervention. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 7(3), 250–267. doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2014.906692

- 23

Education Omnibus Trailer Bill, 2023.

- 24

Gotlieb et al., 2022.

- 25

Jenkins, J. R., Hudson, R. F., & Johnson, E. S. (2007). Screening for at-risk readers in a response to intervention framework. School Psychology Review, 36(4), 582–600. doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2007.12087919

- 26

Miciak & Fletcher, 2020.

- 27

Gaab & Petscher, 2022.

- 28

Baker, D. L., Cummings, K., & Smolkowski, K. (2022). Diagnostic accuracy of Spanish and English screeners with Spanish and English criterion measures for bilingual students in Grades 1 and 2. Journal of School Psychology, 92, 299–323. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2022.04.001; Solano Flores, G. (2016). Assessing English language learners: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- 29

Durán, L., Siebert, J. M., Zegers, M., Gutiérrez, N., Pei, F., et al. (2025). Comparing the performance and growth of linguistically diverse and English-only students on commonly used early literacy measures. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 0(0). doi.org/10.1177/00222194251339470; Solano Flores, 2016.

- 30

Gaab & Petscher, 2022; Sturgell, A. K., Forcht, E. R., & Van Norman, E. R. (2025). A gap in reporting: Student demographic information in academic universal screening studies. Psychology in the Schools, 62: 2766–2777. doi.org/10.1002/pits.23501

- 31

Baker et al., 2022; Solano Flores, 2016.

- 32

Cummings, K. D., Smolkowski, K., & Baker, D. L. (2019). Comparison of literacy screener risk selection between English proficient students and English learners. Learning Disability Quarterly, 44(2), 96–109. doi.org/10.1177/0731948719864408; Ford, K. L., Invernizzi, M. A., & Huang, F. (2014). Predicting first grade reading achievement for Spanish-speaking kindergartners: Is early literacy screening in English valid? Literacy Research and Instruction, 53(4), 269–286. doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2014.931494

- 33

Neuman, S. B., Quintero, E., & Reist, K. (2023). Reading reform across America: A survey of state legislation. Albert Shanker Institute. shankerinstitute.org/read

- 34

Odegard, T. N., Hall, C., & Kloberdanz, K. (2025). Literacy legislation in practice: Implementation, impact, and emerging lessons. Annals of Dyslexia, 75: 401–409. doi.org/10.1007/s11881-025-00348-9; Woulfin, S. L., & Gabriel, R. (2022). Big waves on the rocky shore: A discussion of reading policy, infrastructure, and implementation in the era of science of reading. The Reading Teacher, 76(3), 326–332. doi.org/10.1002/trtr.2153

- 35

Komesidou, R., Feller, M. J., Wolter, J. A., Ricketts, J., Rasner, M. G., et al. (2022). Educators’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to the implementation of screeners for developmental language disorder and dyslexia. Journal of Research in Reading, 45(3), 277–298. doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12381; Ozernov-Palchik, O., Elizee, Z., Catania, F., Hacikamiloglu, M., Shattuck-Hufnagel, S. et al. (2025, August). (Not so) universal literacy screening: A survey of educators reveals variability in implementation. EdArXiv. doi.org/10.35542/osf.io/3zcxh_v1; Tatel, S., Darcy, L. J., Solari, E. J., Conner, C., Hayes, L., et al. (2025). Determinants to implementing a new early literacy screener: Barriers and facilitators. Annals of Dyslexia, 75, 524–546. doi.org/10.1007/s11881-025-00333-2

- 36

Ozernov-Palchik et al., 2025; Tatel et al., 2025.

- 37

Ozernov-Palchik et al., 2025.

- 38

Schraeder, M., Fox, J., & Mohn, R. (2021). K–2 principal knowledge (not leadership) matters for dyslexia intervention. Dyslexia, 27(4), 525–547. doi.org/10.1002/dys.1690

- 39

Cobb, P., Jackson, K., Henrick, E., & Smith, T. M. (2018). Investigating and supporting instructional improvement. In P. Cobb, K. Jackson, E. Henrick, & T. M. Smith (Eds.), Systems for instructional improvement: Creating coherence from the classroom to the district office (pp. 1–14). Harvard Education Press.

- 40

Barrett, C. A. (2021). Using systems-level consultation to establish data systems to monitor coaching in schools: A framework for practice. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 31(4), 411–437. doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2020.1830409

- 41

Tatel et al., 2025.

- 42

Bisht, B., LeClair, Z., Loeb, S., & Sun, M. (2021, November). Paraeducators: Growth, diversity and a dearth of professional supports (EdWorkingPaper No. 21-490). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. doi.org/10.26300/nk1z-c164

- 43

Komesidou et al., 2022; Ozernov-Palchik et al., 2025; Tatel et al., 2025.

- 44

Cobb et al., 2018; Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2014). Can professional environments in schools promote teacher development? Explaining heterogeneity in returns to teaching experience. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(4), 476–500. doi.org/10.3102/0162373713519496

- 45

Ozernov-Palchik et al., 2025.

- 46

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017, June 5). Effective teacher professional development [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-prof-dev; Desimone, L. M., Porter, A. C., Garet, M. S., Yoon, K. S., & Birman, B. F. (2002). Effects of professional development on teachers’ instruction: Results from a three-year longitudinal study. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24(2), 81–112. doi.org/10.3102/01623737024002081

- 47

Science of Reading Center. (2025, July). How is it going? Insights from NYS educators on the implementation of the science of reading. Science of Reading Center, State University of New York at New Paltz. newpaltz.edu/media/science-of-reading/SUNY-New-Paltz-Science-of-Reading-Center-2025-New-York-State-Educator-Survey.pdf

- 48

Science of Reading Center, 2025; Simmons, C. (2023, February 1). Does your school need a curriculum vetting team? ASCD. ascd.org/el/articles/does-your-school-need-a-curriculum-vetting-team

- 49

Tatel et al., 2025.

- 50

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. (2023, June). Early literacy screening guidance and resources. doe.mass.edu/instruction/screening-assessments/guidance.html

- 51

Catts et al., 2013; U.S. Department of Education, 2009.

- 52

Catts & Petscher, 2021; Gotlieb et al., 2022; Miciak & Fletcher, 2020.

- 53

Gotlieb et al., 2022; Lovett, M. W., Frijters, J. C., Wolf, M., Steinbach, K. A., Sevcik, R. A., et al. (2017). Early intervention for children at risk for reading disabilities: The impact of grade at intervention and individual differences on intervention outcomes. Journal of educational psychology, 109(7), 889–914. doi.org/10.1037/edu0000181; Solari et al., 2021; U.S. Department of Education, 2009.

- 54

Gaab & Petscher, 2022.

- 55

Ozernov-Palchik et al., 2025.

- 56

Biancarosa, G., Bryk, A. S., & Dexter, E. R. (2010). Assessing the value-added effects of literacy collaborative professional development on student learning. The Elementary School Journal, 111(1), 7–34. doi.org/10.1086/653468; Blazar, D., McNamara, D., & Blue, G. (2022, May). Instructional coaching personnel and program scalability (EdWorkingPaper No. 21-499). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. doi.org/10.26300/2des-s681; Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. doi.org/10.3102/0034654318759268

- 57

Mississippi Department of Education. (2021). Mississippi Department of Education’s coaching model. mdek12.org/sites/default/files/Offices/MDE/OAE/OEER/Literacy/Administrators/6.7.21_mde_coaching_model_one-pager.pdf

- 58

Komesidou et al., 2022; Ozernov-Palchik et al., 2025; Tatel et al., 2025.

Siebert, J. M., Gomez, D., Silverman, R., & Domingue, B. W. (2025, December). California's adoption of reading difficulties risk screening: Scientific evidence and policy relevance. Policy Analysis for California Education [Policy Brief]. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/californias-adoption-reading-difficulties-risk-screening