TK–12 Education Governance in California

Summary

Reimagining California’s Education Governance System

The report TK–12 Education Governance in California: Past, Present, and Future examines the history of California’s education governance system, analyzes the state of the current system and its effectiveness across six key dimensions, and offers recommendations for realigning roles and responsibilities to create a more coherent education governance system in California. Education governance encompasses the mechanisms through which decisions are made, responsibilities are distributed, and accountability is maintained within the public education system.

The question ‘Who is responsible to whom, and for what?’ remains unresolved in California’s education governance system, resulting in blurred lines of responsibility and difficulty making systemic improvement.”

TK–12 EDUCATION GOVERNANCE IN CALIFORNIA, 2025

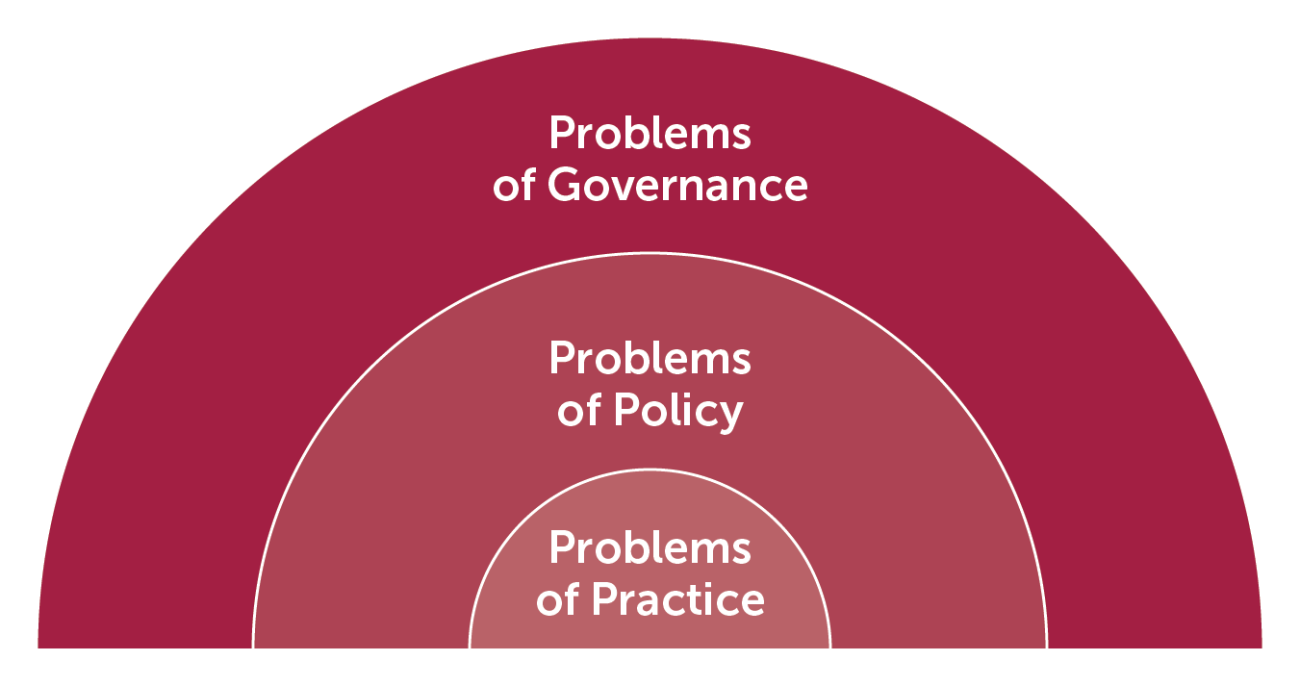

Problems of Governance Cascade Through the Education System

California’s education system faces interconnected challenges at three levels (Figure 1): problems of governance (unclear roles, fragmented authority) create problems of policy (underdeveloped or incoherent laws and guidance), which can then manifest as problems of practice (challenges in classrooms). This report focuses on governance challenges that give rise to problems of policy and practice, and offers recommendations for how to address them.

Figure 1. Nested Problems in Education: Governance, Policy, and Practice

History of Governance Reform in California

1849–1970: Repeated Attempts to Resolve California’s “Double-Headed System”

- 1849 The first constitution of California established the elected superintendent of public instruction (SPI).

- 1852 and 1912 The State Board of Education (SBE) was created; a 1912 amendment to the state constitution gave the governor the power to appoint SBE members, splitting authority between the SPI and the SBE.

- 1920 The Jones Report warned that the “double-headed system” of an elected SPI and governor-appointed SBE causes conflict and recommended unifying leadership under an appointed commissioner.

- 1921 The California Department of Education (CDE) was formed to centralize administration under the SPI, with policy authority retained by the SBE.

- 1928–1968 Multiple ballot measures to eliminate the elected SPI and resolve governance conflicts were put before voters but failed.

- 1944–1945 The Mills and Strayer reports identified confusion, weak capacity, and unclear authority in California’s education governance and called for a single appointed SPI and stronger SBE oversight.

- 1963–1967 The Little Reports and Attorney General opinion reaffirmed governance incoherence and urged that the SPI be accountable to the SBE.

The present California educational organization must be regarded as temporary and transitional, and dangerous for the future, and it should be superseded at the earliest opportunity by a more rational form of state educational organization.”

THE JONES REPORT, 1920

1970–2012: Centralization of Education Governance

|

Beginning in the 1970s, California shifted from a highly decentralized, locally funded education system towards greater state involvement in response to significant legal, social, economic, and political pressures:

|

For the last two decades, there has been a national movement to micromanage teachers from afar, through increasingly minute and prescriptive state and federal regulations. California successfully fought that movement and has now changed its overly intrusive, test-heavy state control to a true system of local accountability.”

GOVERNOR JERRY BROWN, 2016

2013 to Present: Localization of Education Governance

| Enacted in 2013, the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) introduced new accountability and support structures: the Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP), the California School Dashboard, and the Statewide System of Support. This reform replaced California’s complex and outdated school finance system with an equity-focused model that allocates funding based on student needs, directing additional resources to English learners, low-income students, and youth in foster care. LCFF provided districts with greater local authority to allocate resources and required districts to engage stakeholders in decision-making. |

|

Although the LCFF delegated decision-making and operational authority to districts, the state nevertheless retains its constitutional responsibility to ensure equal learning opportunities for all students. According to the California Supreme Court:

The State itself bears the ultimate authority and responsibility to ensure that its district-based system of common schools provides basic equality of educational opportunity.”

BUTT V. STATE OF CALIFORNIA, 1992

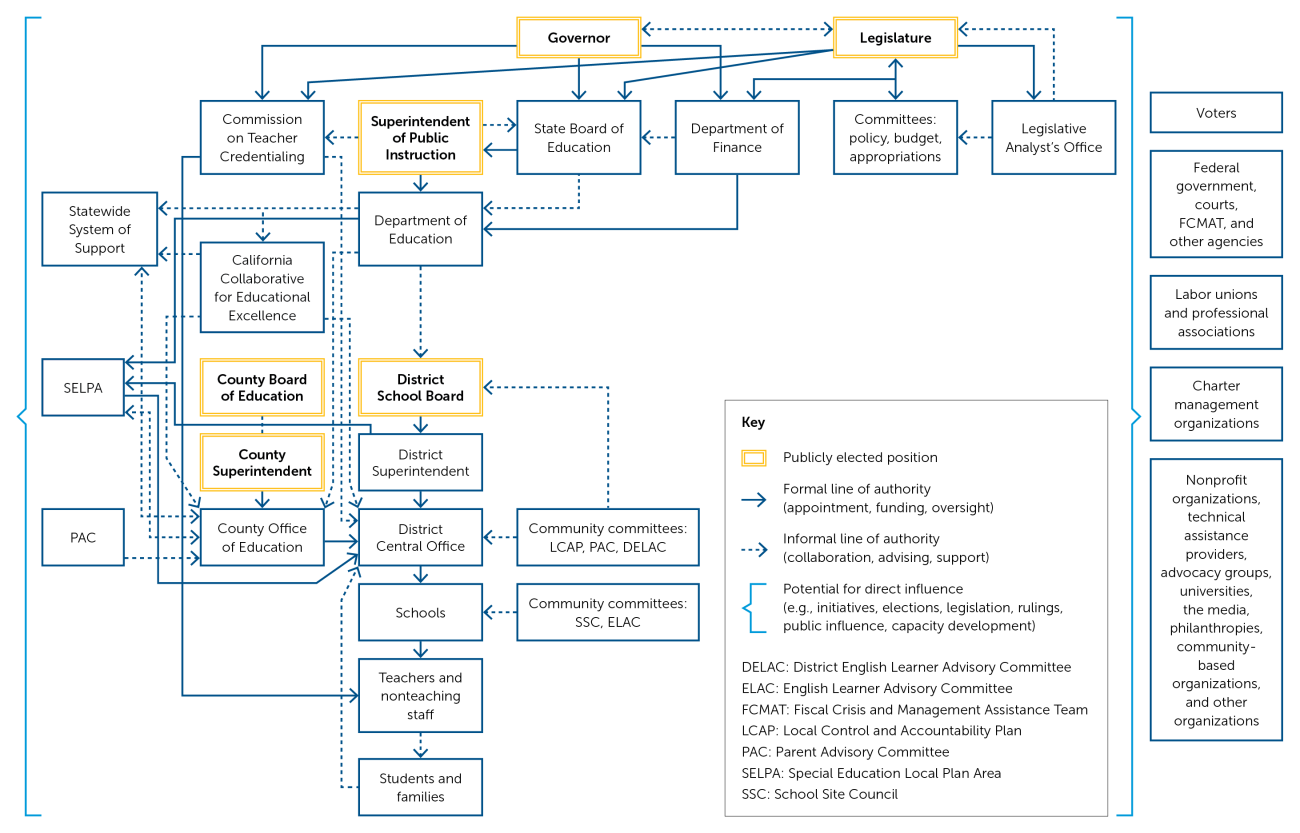

Mapping California’s Governance System: Complexity and the Challenge of Coherence

California exercises its constitutional responsibility for education equity through a governance system that distributes authority across state, regional, and local levels. This decentralized structure is intended to foster responsiveness and local adaptation but also produces overlapping roles, blurred accountability, and limited coherence. The result is a system where authority is shared and divided—a persistent governance challenge ().

Figure 2. Map of California’s TK–12 Education Governance System

What Effective Education Governance Systems Do

As guidance, this study drew on the elements of effective education governance developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)—an empirically grounded model that defines six key dimensions of high-functioning education governance systems.

- Strategic thinking: Maintain a long-term vision for improvement.

- Accountability: Establish transparent mechanisms to hold actors responsible for performance and continuous improvement.

- Capacity: Ensure that people and institutions have the resources, training, and infrastructure to perform their roles effectively.

- Knowledge governance: Produce and use data and research to inform decisions and foster a culture of learning.

- Stakeholder involvement: Engage diverse voices throughout the policymaking process to create inclusive, responsive governance.

- Whole-of-system perspective: Coordinate efforts across sectors and levels of the system to achieve shared goals for students.

Taking Stock of the Effectiveness of California’s Education Governance System

This study engaged former and current policymakers, researchers, and education leaders to assess California’s education governance strengths and challenges along the six OECD dimensions of effective governance. From December 2023 to June 2024, we conducted purposive interviews with 16 experts in California’s education system. On average, participants rated the system’s effectiveness at 2.8 on a five-point scale (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = fair, 4 = good, 5 = excellent), indicating a general perception of performance between “poor” and “fair.” Our interviews yielded a broad and nuanced understanding of the key factors contributing to California’s education governance challenges.

Key Findings

Interviews revealed that California’s education governance system faces significant challenges across three interconnected areas: incentives, capacity, and funding. These issues affect how well the system aligns responsibilities, sustains policy implementation, and supports equitable outcomes.

Incentives. Misaligned accountability and fragmented authority undermine coherence in policymaking and implementation. The state’s complex structure of elected and appointed offices creates competing incentives and short-term political pressures that disrupt long-term implementation. Legislative action often reflects visibility and urgency over strategic planning while diffuse accountability and limited transparency weaken efforts to advance equity. Although the LCFF was intended to improve outcomes and equity, the absence of clear lines of authority, transparent resource use, and meaningful incentives for improvement has produced gaps in responsibility and a reliance on litigation to protect students’ rights.

Capacity. Across state, regional, and local levels, institutions and actors are expected to execute complex directives with limited expertise, authority, or resources. Districts struggle to manage overlapping initiatives, administrative burdens, and leadership turnover; local boards vary in governance capacity; and the quality and intensity of supports from County Offices of Education (COEs) are inconsistent across the state. Although mechanisms for state intervention exist, they are limited in scope and lack the authority or coherence needed to drive meaningful improvement.

Funding. Fiscal instability constrains coherent governance. Reliance on volatile income tax revenue, the limitations of Propositions 13 and 98, and the prevalence of one-time grants hinder long-term planning and investment. State agencies also face staffing and pay constraints that reduce operational capacity.

Overall, the findings point to a governance system hampered by misaligned incentives, uneven capacity, and unpredictable funding. Strengthening coherence requires clarifying roles, aligning authority with responsibility, and building sustainable capacity and fiscal infrastructure across all levels of the system.

Recommendations: Reimagining Education Governance in California

What concrete steps can California take to build greater coherence and capacity across its TK–12 education system?

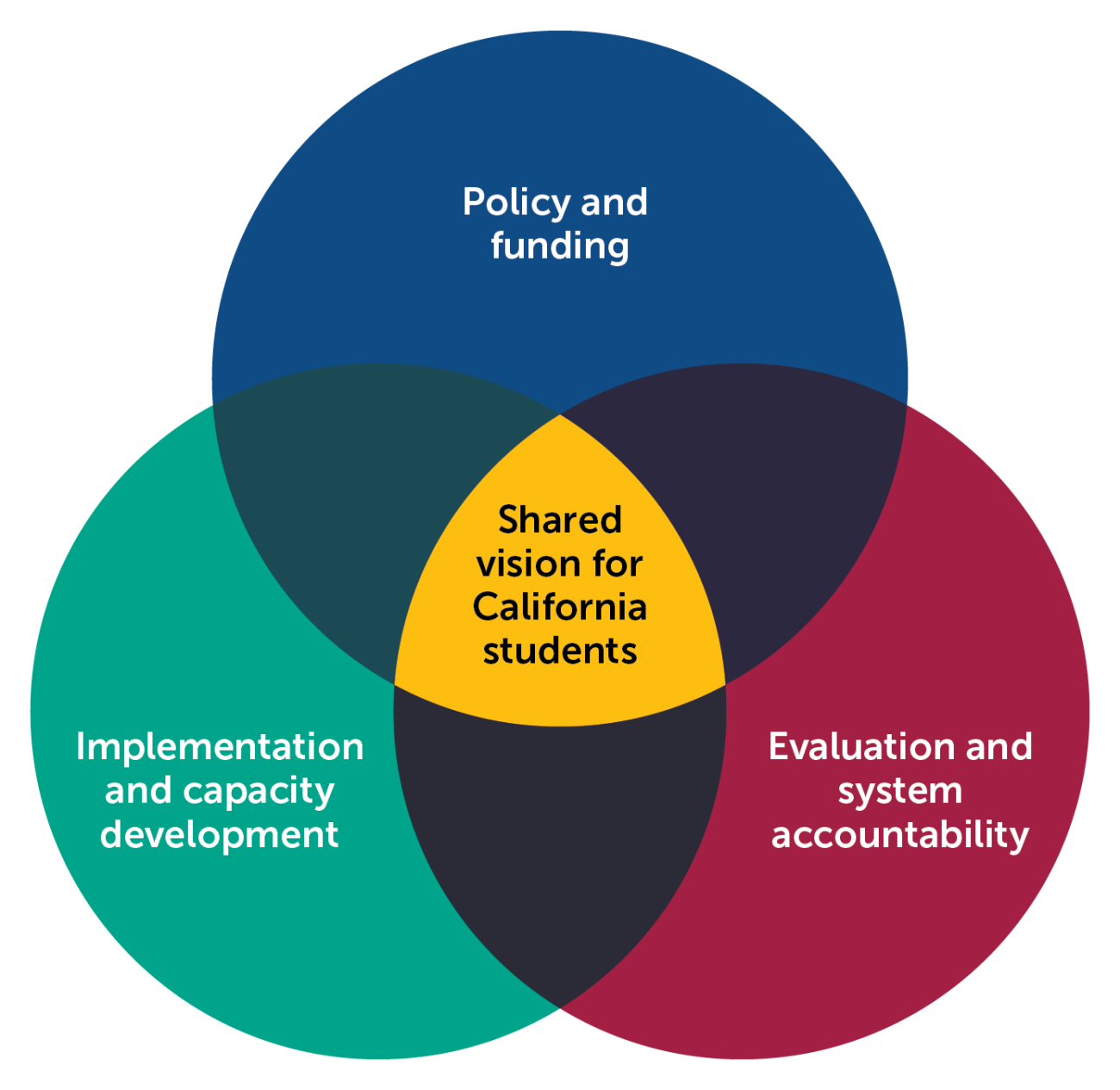

Insights from a PACE expert convening in February 2025 underscored the importance of clarifying roles in California’s education governance system—specifically, who is responsible for what? These insights informed a three-domain framework for effective governance that aligns policy and funding, implementation and capacity development, and evaluation and system accountability, all centered on a shared vision for student learning.

Reframing California’s Education Governance: Three Interconnected Domains of Responsibility

|

A more coherent and functional governance system in California would set a well-articulated, shared vision and organize the following domains in pursuit of that vision (Figure 3):

|

Figure 3. Domains of Education Governance Responsibilities in California

|

New Pathways for Coherent Education Governance in California

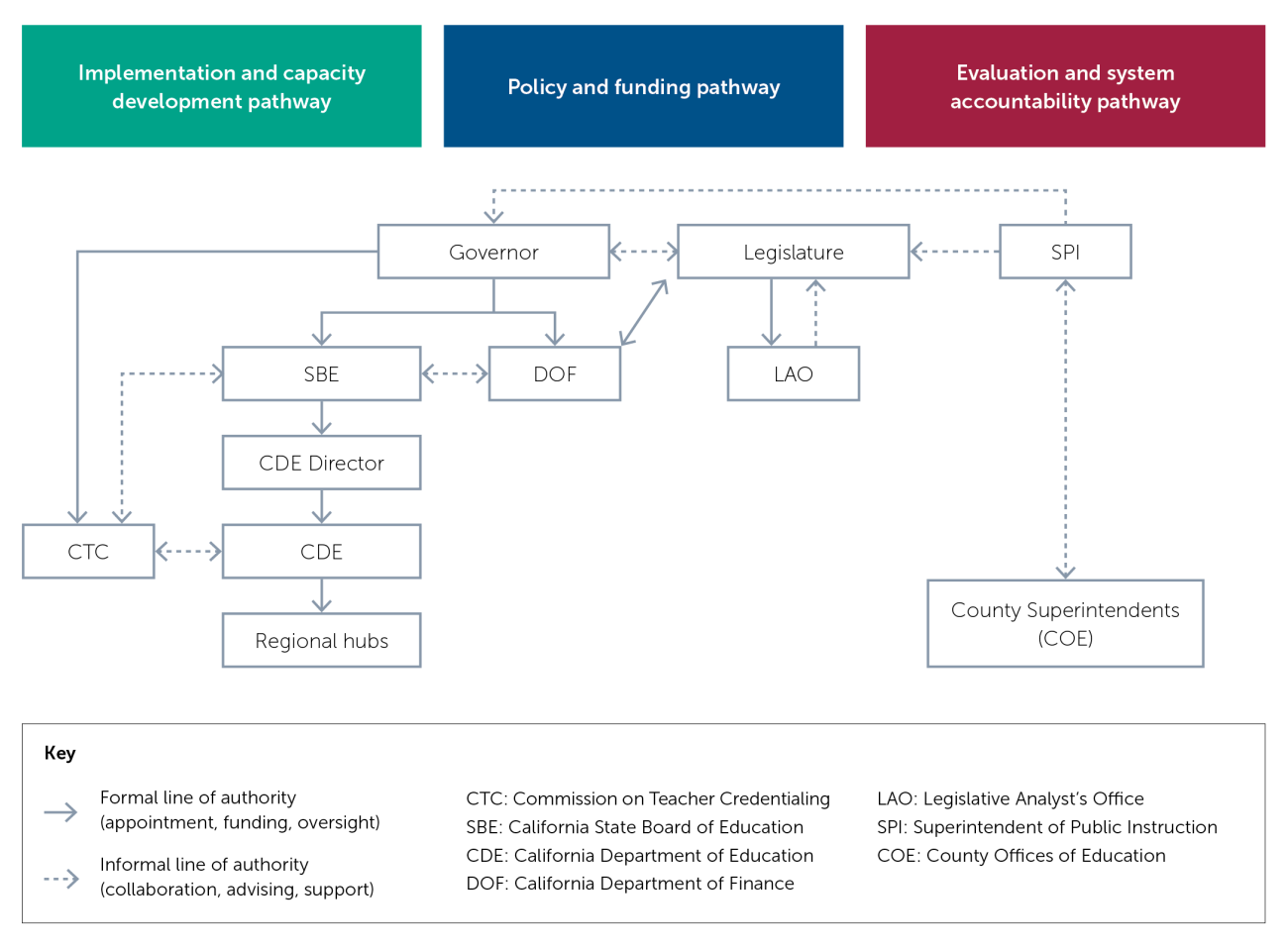

A primary goal of this proposed model is to shift from a system in which roles and authority are unclear—leading to fragmentation and incoherence—towards a system in which every system actor is aligned around supporting districts and schools to serve students more effectively. Achieving this shift requires cultivating a sense of shared responsibility for student outcomes from the state level to the classroom. A reimagined state education governance system would align roles and responsibilities as described in the following sections to ensure coherence and collective accountability for student success.

A Key Lever for System Coherence: Reconceptualizing the Role of the SPI

California’s education governance system is fragmented by design, with a double-headed structure that divides authority between the elected SPI and the governor and SBE. This arrangement blurs policy-setting and implementation roles, often resulting in overlapping responsibilities, shallow accountability, and inconsistent coordination among key entities. Rather than resolving these structural tensions, additional policies and agencies have been layered onto this already divided framework, compounding fragmentation and inefficiency.

Numerous past reform efforts have sought to change the SPI from an elected to an appointed position, but all such ballot initiatives have been rejected by voters. A more pragmatic and immediately actionable approach lies in redefining the SPI’s statutory responsibilities—clarifying the relationships of the governor, SPI, SBE, and CDE—to align authority with incentives and foster systemwide coherence. This approach would keep the SPI as an elected position but change the responsibilities of the SPI to position the governor as the chief architect and steward responsible for aligning and advancing California’s education system. The CDE would be led by a director appointed by the SBE, and the redefined role of the SPI would provide leadership in evaluation and system accountability.

Realigned Roles in the Proposed Domains of Education Governance

The following recommendations begin to outline, at a high level, the responsibilities and pathways of interagency relationships necessary to carry out effectively the functions within each domain of education governance.

Policy and Funding Pathway

The governor would hold clear responsibility for the state’s TK–12 system, establishing statewide priorities and shaping policy through the budget process. The governor’s budget proposal, developed in partnership with the Department of Finance, would allocate resources to reflect these priorities, steering the state’s investment in public education and guiding the work of state and local educational agencies.

The legislature would continue to negotiate policy and appropriations, enact laws, and, informed by the Legislative Analyst’s Office, provide fiscal and policy oversight to ensure the equitable implementation of state policy.

The SBE would continue to translate laws into standards, frameworks, and accountability systems that guide policy and practice statewide. Composed of experts in education policy and practice, the SBE under this new model would appoint a CDE director with the experience and expertise to lead the CDE’s work of implementing state policy, building local capacity, and ensuring coherence and equity across California’s education system.

Implementation and Capacity-Development Pathway

Now appointed by the SBE and confirmed by the Senate, the CDE director would develop comprehensive, user-centered implementation frameworks and administer programs that translate policy into effective practice.

The CDE would function as a trusted source for professional learning, technical assistance, and implementation support, helping districts build capacity to deliver on state priorities and working in close coordination with the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing to ensure that students have access to well-prepared, effective educators.

The CDE would establish and oversee regional hubs for implementation and capacity development to provide districts with locally responsive, adaptive support to implement state priorities, with clear lines of authority and accountability flowing from the state. Under this model, divisions and staff within current COEs as well as agencies such as the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE)—that is, those with deep expertise, regional connections, and capacity to support district and school improvements—would take on leading roles within these regional hubs.

Evaluation and System Accountability Pathway

Elected by California voters, the SPI would now serve as a nonpartisan evaluator and champion for students, conducting and coordinating rigorous, formative evaluations to inform policy and program improvement, and using the office’s bully pulpit to elevate issues of equity and to advocate for all students. Working in coordination with the CDE and California’s Cradle-to-Career longitudinal data system, which links information from early education through postsecondary and the workforce, the SPI would access and analyze statewide data to understand system performance for students. The SPI’s reports would inform the governor, legislature, and other policy leaders, strengthening evidence-based policymaking and transparency across the education system.

With the CDE leading professional learning and technical assistance, COEs could focus on their unique local strengths: rigorously evaluating district LCAPs and finances, and coordinating countywide resources to support students’ whole child needs. COEs could serve as fiscal sponsors for the CDE’s regional hubs for implementation and capacity development. COEs and the SPI could participate in a network of shared responsibilities and common interests, focused on leveraging evaluation and system accountability to meet students’ needs.

Adopting a model in which the SBE appoints the CDE director would ensure that the agency is led by someone with deep expertise in education administration and would reduce confusion, create a more coherent and integrated system, and bring California in line with the plurality of states that use this governance structure. Twenty states nationwide, including Massachusetts, New York, Florida, and Mississippi, have a governance model in which the state board appoints the chief state school officer.

Establishing distinct leadership for evaluation and system accountability, apart from implementation, would strengthen public trust and institutional balance by avoiding self-evaluation within the executive branch. This shift would move California from a reactive, litigation-driven approach to system accountability towards a proactive, learning-oriented system that fosters transparency, coherence, and continuous improvement (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A Reimagined State-Level Education Governance System

Conclusion

While each pathway addresses a distinct set of state-level governance responsibilities, the effectiveness of the restructured system depends on how well the elements of all three pathways function together. A reimagined policy and funding pathway—led by the governor with the legislature and SBE—would bring needed coherence to policy development and budget planning. The implementation and capacity-development pathway—led by a CDE director appointed by the SBE—would ensure that policies are translated into practice through coordinated state, regional, and local support systems that invest in providing practical guidance, professional learning, and technical assistance. The evaluation and system accountability pathway—anchored by a redefined SPI role—would provide independent, evidence-based feedback on how policies are working for California’s students, informing continuous improvement across the system.

The need for stronger, more coherent governance has never been greater. Schools are grappling with fiscal challenges alongside deepening inequities, persistent opportunity gaps, and the lasting impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on student learning and well-being. With the federal government now taking a diminished role in oversight, accountability, and research, California must take bold, strategic steps to build a governance system that is coherent, centered on equity, and responsive to the needs of all students.

Figures 2 and 4 were updated for clarity in January 2026.

Myung, J., Hough, H. J., & Marsh, J. A. (2025, December). TK–12 education governance in California Past, present, and future [Report]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/tk-12-education-governance-california