Excess Revenue, Unequal Opportunity

Summary

California’s school funding formula for transitional kindergarten (TK) through Grade 12 is designed to direct more resources to students with greater need. However, some districts—known as basic aid districts (also called “community-funded” or “excess-tax” districts)—generate more funding from local property taxes than the state calculates they need under the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Basic aid districts keep their property tax revenues, often ending up with thousands of dollars more per student than other districts.

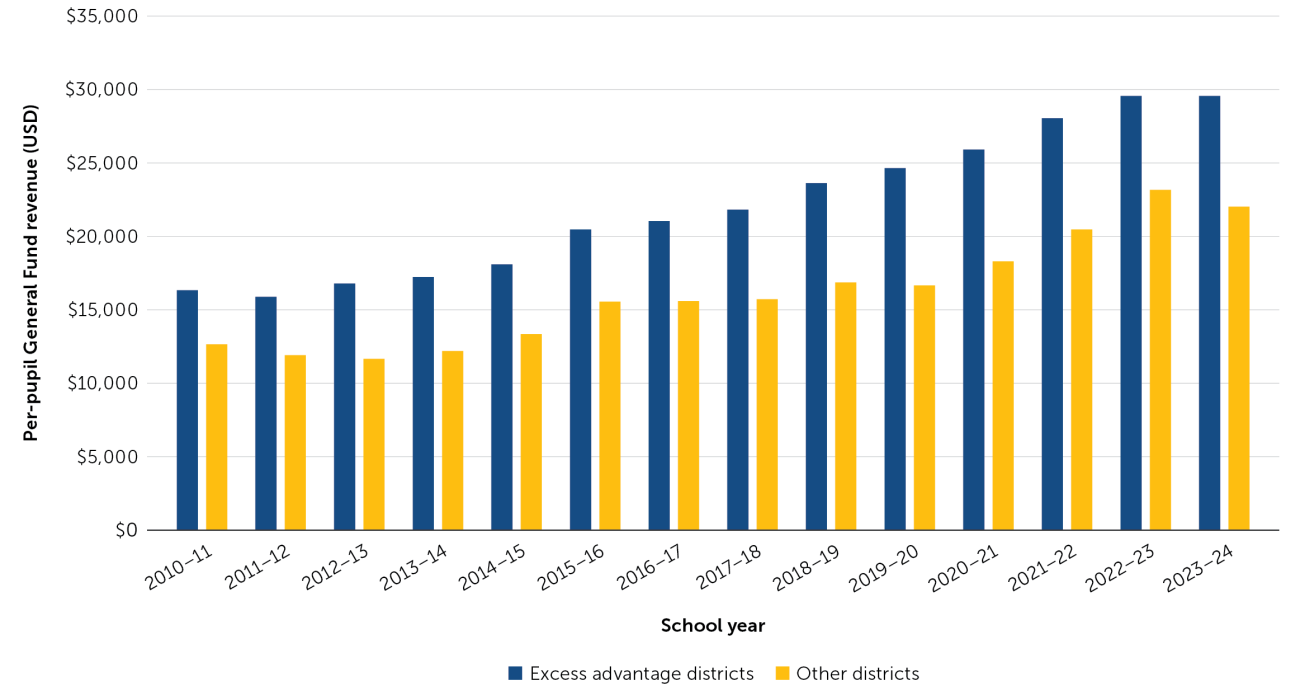

This report, the first major study on basic aid since the enactment of the LCFF, finds that 139 districts serving just 5.5 percent of California’s TK–12 students are benefitting from funding advantages that are growing over time. Excess local revenue in basic aid districts has risen 41 percent (17 percent when adjusted for inflation) over 5 years—outpacing LCFF growth and widening the gap between property-rich districts and those that rely on state aid.

In analyzing disparities between basic aid districts and their peers, this report focuses on a subset of 50 well-resourced districts—those with both high excess revenues and low percentages of high-need students (e.g., students from low-income households, English learner students, students in foster care)—that capture the majority of these funding advantages (see figure). Concentrated in property-rich areas of 19 counties statewide—most notably San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Barbara, San Diego, and Marin—these “excess advantage” districts collectively generated $1.15 billion in excess revenue, representing 87 percent of the statewide basic aid total in school year 2023–24.

Substantial per-pupil funding gaps between excess advantage and other districts create tangible resource disparities that affect teachers and students alike. These gaps strengthen excess advantage districts’ ability to offer far higher salaries and have smaller class sizes than surrounding districts, intensifying competition for qualified teachers and leaving neighboring districts struggling to recruit and retain staff.

Excess local revenue in basic aid districts has risen 41 percent (17 percent when adjusted for inflation) over 5 years—outpacing LCFF growth and widening the gap between property-rich districts and those that rely on state aid. These “excess advantage” districts collectively generated $1.15 billion in excess revenue, representing 87 percent of California’s basic aid total in school year 2023–24.

Per-Pupil General Fund Revenue Over Time in Excess Advantage Districts Compared to Other Districts

Note. Data are from California Department of Education statewide LCFF summary data, Advance Apportionment Average Daily Attendance: Section 75.70; Ed-Data. This analysis uses school year 2023–24 high-excess, low-need basic aid districts as a comparison for each year. Inflation is school-year adjusted.

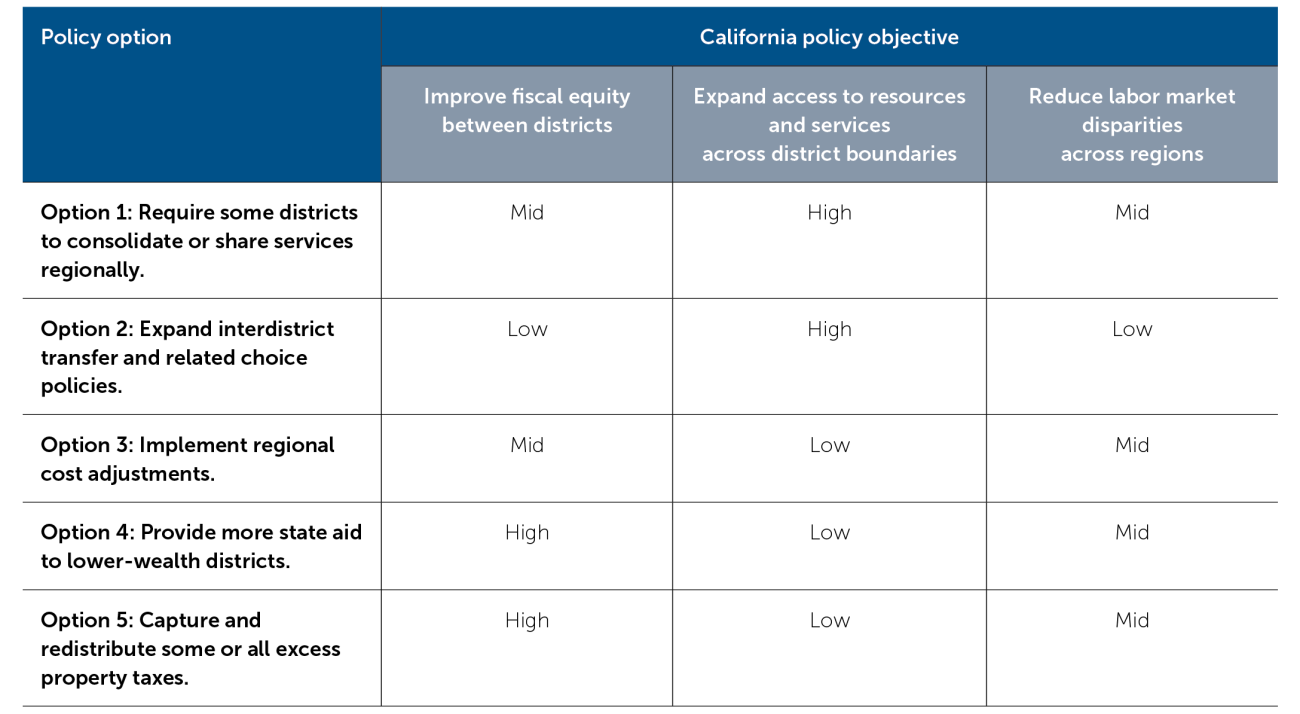

This analysis of the funding patterns, demographic profiles, and resource gaps of California’s basic aid districts highlights five policy options that state lawmakers and education interest holders can take to address these disparities:

- Require some districts to consolidate or share services regionally.

- Expand interdistrict transfer and related choice policies.

- Implement regional cost adjustments.

- Provide more state aid to lower-wealth districts.

- Capture and redistribute some or all excess property tax revenues.

California’s school finance system has been designed with equity in mind, but the resource disparities created by excess advantage districts risk undermining that principle. Policymakers face important choices about whether and how to address the disparities resulting from excess resources so that all students benefit, regardless of where they live. The policy options outlined in this report provide potential pathways to move the system closer to funding fairness.'

Assessment of How Likely Each Basic Aid Policy Option Is to Achieve Various State Objectives

Authors’ Acknowledgments. We would like to thank the experts who shared their knowledge with us to inform our work as well as Todd Collins, the Give Forward Foundation, the Ken and Jaclyn Broad Family Fund, the Bay Area Tutoring Association, the Siegelman Family Trust,the Silicon Valley Education Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation for their financial support of this project.

Hahnel, C., Zamarripa, S., & Gallagher, H. A. (2025, October). Excess revenue, unequal opportunity: Revisiting basic aid in the LCFF era [Policy brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/excess-revenue-unequal-opportunity-revisiting-basic-aid-lcff-era