The California College Promise

Summary

This brief describes the types of college promises that exist in the state of California. In doing so, we summarize existing research on this topic. Furthermore, we provide a framework to study the California Promise Program in community colleges in California. We use publicly available data to highlight key aspects of our proposed framework: What are we promising, to whom, and where? We end our brief by providing key recommendations to ensure that the promise extends to the most vulnerable groups of students to help in closing equity gaps in college degree and completion in California.

A Promise to What?

In the last decade, college promise programs have been implemented to address concerns of college affordability and to increase college access and attainment in several communities and states across the United States. These promise programs provide additional financial aid to students on top of existing aid through place-based scholarships and grants.

While versions of promise programs have existed in some form since the 1950s, it was not until the announcement of Michigan's Kalamazoo Promise in 2005 that they gained national attention and proliferated across the country. Between 2006 and 2016, approximately 125 promise programs launched and, as of 2016, 31 states have at least one promise program. California is no exception to this national trend. In the last decade, it established its own free college program— the statewide program also known as the California College Promise—and several place-based college scholarships (e.g., Long Beach College Promise and Los Angeles County Promises that Count). As indicated earlier, these promises respond to Californians' concerns around college affordability (as we reported in the PACE brief College Affordability in Every Corner of California), as well as broader inequities that result in lower rates of college access and attainment among the most vulnerable groups of students, including (but not limited to) low-income students, immigrant students, English language learners, students of color, first-generation students, LGBTQ students, returning veterans, and foster youth. However, these programs vary greatly in terms of their goals and eligibility requirements; how they are funded; and the ways in which they allocate funds. Table 1 (see full brief) provides a typology of promise programs in California to illustrate the different designs and structures of each program. While this table is not comprehensive, it provides a framework to think about the types of programs that currently exist in the state and the types of students who are targeted by those programs.

As seen in Table 1 (in the full brief), promise programs take many forms and require, in some cases, the involvement of various state and local partnerships. For example, community colleges need to coordinate efforts with K–12 districts and with four-year institutions to determine eligibility requirements, as well as to coordinate implementation of their promise program—as was the case with the Long Beach Promise 2.0. Similarly, private foundations must join public institutions' efforts to support the establishment and expansion of local promise programs. In Los Angeles County, the Promises that Count initiative aims to bolster existing promise programs at seven institutions across the county through the establishment of a support network comprised of promise program leaders and coordinated by the nonprofit organization WestEd. Each of these local initiatives coexists with the state's newest community college funding program established through Assembly Bill 19 (AB 19), which provides fee waivers and grants for other educational costs to students who meet specific requirements under a "promise program" nomenclature. The precise language of AB 19 states that it is intended to support the California Community College (CCC) system in accomplishing all of the following goals: increasing the number of high school students who are prepared for and attend college; increasing the percentage of students who earn credentials at community colleges; increasing the percentage of students who transfer to California State University and University of California institutions; and reducing and eliminating regional achievement gaps and achievement gaps for students from groups that are underrepresented at the California Community Colleges, including, but not limited to, low-income students, students who are current or former foster youth, students with disabilities, formerly incarcerated students, undocumented students, and students who are veterans.

What we learned from this brief descriptive exercise is that:

- Promise programs in California are not necessarily universal and have tremendous variation in their definition and structure (e.g., goals, design, scope, funding, beneficiaries, etc.).

- Implementation of promise programs varies widely, depending on institutional and regional capacities and resources.

- Extensive eligibility requirements affect who can benefit from various promise programs.

- Virtually no research exists that examines the impact, efficiency, effectiveness, and equity dimensions of California's numerous promise programs.

While it is important to know the design features of the state's promise programs, this brief focuses attention on providing a framework to examine more closely the state's California College Promise program adopted through AB 19. The CCC plays a critical role in addressing inequities in college degree completion because the community college sector is the largest and most accessible system of higher education in California. Most California college students start their college trajectories at one or more of the state's 115 community colleges, which educate over 2.1 million students (44 percent of the state's higher education enrollment), making CCC institutions essential to helping California meet its current and future workforce needs. Unfortunately, while the CCC system has the lowest tuition rates in California—and while over 1 million students receive $2.8 billion in local, state, and federal financial aid annually—the average net price for a low-income student attending a CCC is significantly higher than attending the other public universities in California once the total cost of attendance (minus tuition waivers, grants, scholarships, or gifts), including the cost of books, transportation, health care, child care, food, and other important needs, are factored in. In fact, low-income students enrolled in CCCs would need to spend, on average, about 50 percent of their and their family's income in order to cover the total cost of attendance. Consequently, the state's most vulnerable college students face the most severe financial burdens in pursuit of a higher education credential. It is precisely for these reasons that AB 19 was created.

What is the California College Promise?

There is no single definition but, for the purposes of this brief, the California College Promise program established through AB 19 is distinct from existing state financial aid sources in that it provides districts/colleges with funds to waive some or all tuition and fees for a significant subset of students (i.e., first-time, full-time students who complete a financial aid application) if the district chooses to use funds for student financial aid. Importantly, the California College Promise established by AB 19 is not the same as the California College Promise Grant (CCPG; formerly known as the Board of Governors Fee Waiver). The CCPG waives tuition for part-time and full-time students who qualify for some form of need-based assistance. It is possible, then, that some students who meet the requirements for AB 19 also meet the income eligibility requirements for the CCPG, such that students might have tuition and fees waived with the CCPG and thus be able to access AB 19 funds for other educational costs. A key component of AB 19 is that it gives districts the discretion "to decide what is the best for their students, whether that is to cover fees for first-time, full-time students or make use of program funding in other ways that meet the goals of the legislation. Each district and each college may implement the California College Promise (AB 19) in different ways."

How are Colleges and Districts Implementing AB 19 Across California?

From the only available report and publicly available data on this topic, we know that:

- In 2018–19, 105 colleges received AB 19 funds. This number is expected to grow in the next years. Of those colleges, 65 institutions awarded financial aid to students using AB 19 funds according to publicly available CCC data.

- Programs are relatively new—56 percent of them have only existed for one or two years.

- Most students benefitting from AB 19 are first-time, full-time students.

- Colleges are using funds in a variety of ways. The top three spending categories include: tuition and/or fees, hiring of staff, and educational costs (most commonly textbook vouchers, transportation assistance, and food vouchers)

- Colleges are combining various streams of funding (e.g., AB 19 with the Student- Centered Funding Formula) to provide comprehensive supports for students.

- Colleges report significant equity concerns, specifically that students benefitting from the program are not the ones who need it most (e.g., low-income students of color).

A Promise to What and for Whom?

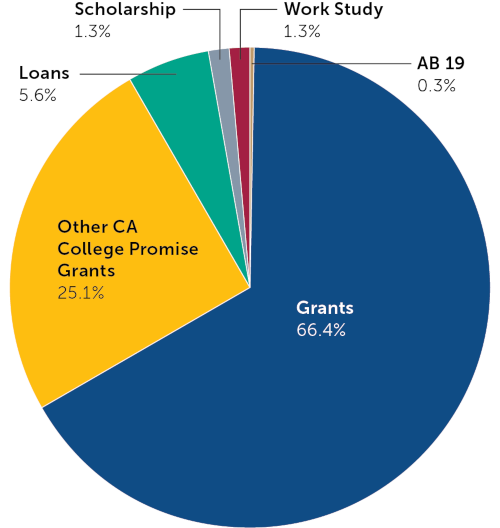

As stated earlier, additional research is needed to describe the demographic profile of students who benefit from AB 19—precisely the goal of this brief. In the following sections, we present descriptive analyses of publicly available data to better understand what the state is promising and to whom. A notable limitation in the data is that we are only able to document institutions and funds that went to students as financial aid, either as a fee waiver or grant for other educational costs, and cannot pinpoint precisely how other AB 19 funding was spent. Nonetheless, the majority of institutions that were allocated AB 19 funding used some or all for student financial aid. As seen in Figure 1, funding from AB 19 accounts for just over $14 million, comprising a small fraction of the more than $2 billion of student financial aid received by CCC students during the 2018–19 academic year.

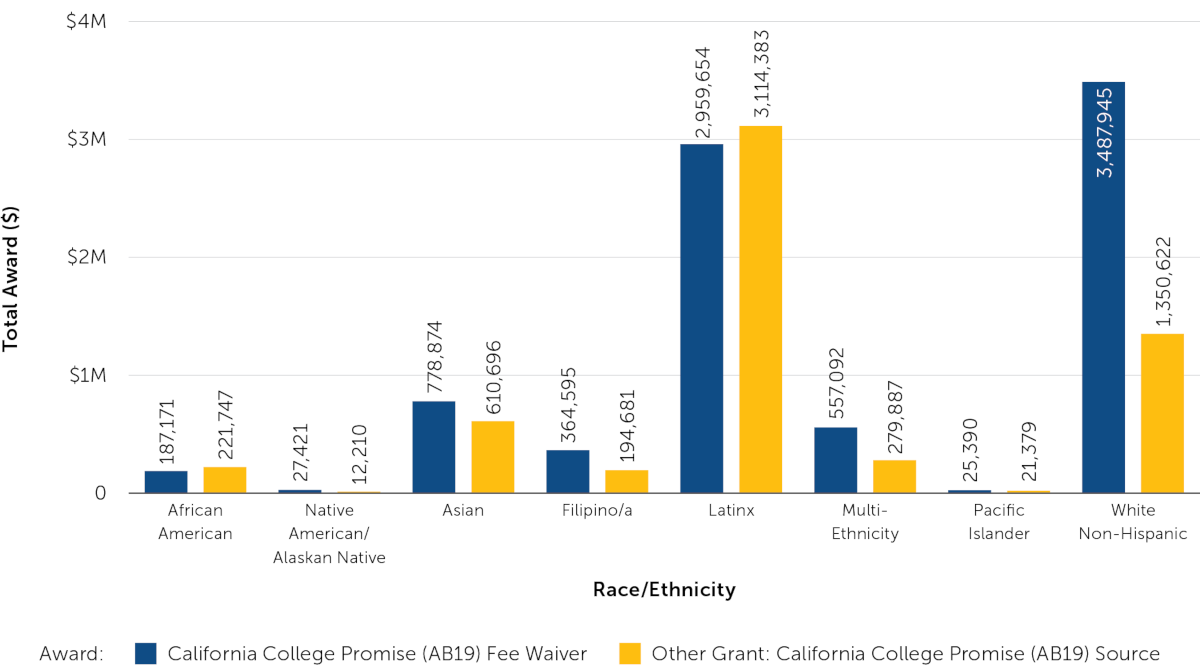

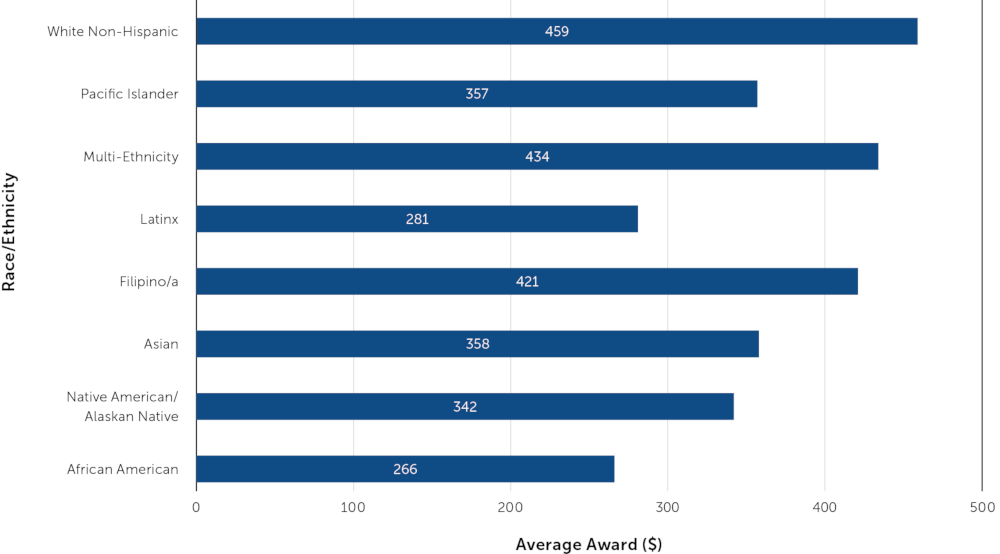

As with other financial aid sources, such as federal work study and student loan programs, districts and colleges are granted considerable discretion in how they allocate and distribute funds from AB 19. Such discretion has resulted in disparities across racial and ethnic subgroups (aggregated and coded by CCC), shown in graphs below. First, there are differences in the amount of aid awarded for fee waivers and for other educational costs, such as books and transportation vouchers. Latinx and White students received the most financial aid from AB 19 funding. A majority of aid for White students went to fees, while the bulk of financial aid from AB 19 funds for Latinx students covered other costs (see Figure 2). The average financial aid award from AB 19 funds for White students during 2018–2019 was $459.20 compared to just $265.53 for African American students (see Figure 3). Similarly, Latinx students are receiving, on average, significantly less funding from AB 19 compared to White students ($281.37 versus $459.20).

Two noteworthy points emerge from these data, namely that AB 19 funding comprises a small proportion of overall spending and that it is unevenly distributed across students from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. The decentralized financial aid system that affords discretion to districts and institutions to opt in and distribute various sources of financial aid (such as AB 19 funding and federal student loans) results in inequities in amount and type of aid received. Unlike the federal student loan program, however, AB 19 is explicitly designed to reduce achievement gaps among underrepresented students in the CCC system.

A growing equity concern is that, while most of the beneficiaries of AB 19 are first-time, full-time students, many vulnerable students are attending part time because affording the total cost of attendance is impossible without some form of employment—and, in some cases, low-income students also have to help their families financially. An overwhelming majority of CCC students (70 percent) are enrolled part time, a trend that has persisted for over a decade. Part-time students are thus facing a significant barrier to meet full-time enrollment requirements to benefit from the California College Promise.

A Promise to What for Whom and Where?

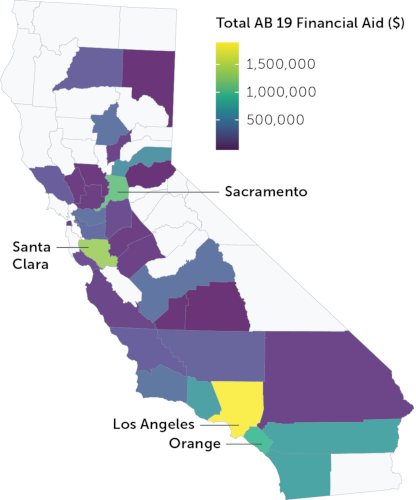

The uneven distribution of financial aid awarded from AB 19 funds across racial and ethnic subgroups is also visible across the state's diverse geography. Over 40 percent of the $14 million in financial aid from AB 19 funds allocated during the 2018–19 academic year is concentrated in just four California counties: Sacramento, Santa Clara, Los Angeles, and Orange (see Figure 4). What's more, institutions in 25 counties did not distribute any AB 19 funding at all. This is significant, as text from the bill explicitly states "reducing and eliminating regional achievement gaps" as a primary goal.

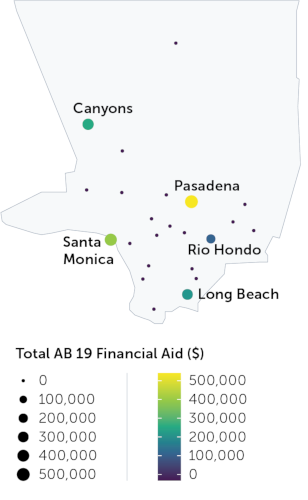

But even in Los Angeles County, only five institutions reported awarding financial aid from AB 19 funds to their students (see Figure 5). The remaining institutions in the county, like institutions in the Los Angeles Community College District, maintain robust promise programs that provide aid to students, but nonetheless did not use AB 19 funds for student financial aid. As the maps show, where students live and where they attend college can have significant effects on access to promise program funding. These issues are especially critical in areas such as the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles County, where students experience particularly high costs of living in addition to core educational expenses.

Conclusion

This brief highlights the landscape of promise programs in California and shows that the design and implementation of the California College Promise established by AB 19 needs to be more carefully and systematically examined. We are aware that some of these programs are relatively new and that complete data to examine their impact are not readily available. However, failure to examine in depth whether the California College Promise meets its goals will continue to perpetuate inequities in college access and completion among groups of students most susceptible to not completing college. Using descriptive data, we discovered that students in racial and ethnic subgroups are not benefitting equally relative to White students from financial aid allocated through AB 19 funds. We also found important regional discrepancies in how institutions are allocating student financial aid from AB 19 funds.

Recommendations

- Revise eligibility criteria. We invite CCCs to review their own eligibility criteria and to examine whether these criteria, in particular the first-time, full-time status requirement, will help reduce inequities. Evidence presented in this brief—and from other descriptive data on who attends community colleges—illustrates that a high proportion of vulnerable students will not be eligible to benefit from California's promise programs. We are concerned with the fact that a significant number of part-time students will be completely left out of the promise. Eliminating all or some existing requirements and strengthening local partnerships may help California actualize the promise and reach those students who need it most. Also, as AB 19 expands, state leaders and institutions should pay particular attention to finding a more equitable allocation of AB 19 funding that better serves students from underrepresented groups.

- Invest in a public campaign to clarify what is being promised and to whom. Given the complex structure of the programs and the fact that multiple promises may exist within the same college, we urge the state of California to invest in a marketing campaign that simplifies the message sent to students, families, and communities regarding the requirements and benefits of the California College Promise. Students should be able to clearly understand what is the total cost of attendance and for which funds they are eligible. Similarly, the public in general can benefit from a single message that describes the goal of the California College Promise: colleges are using AB 19 funds not just for tuition and fees but also to provide services and programs to students in need and to hire staff.

- Invest in research studies. The state and its CCC system partners should provide incentives to institutions and researchers to collaborate in examining the impact, efficiency, effectiveness, and equity dimensions of the California College Promise. Unfortunately, we do not know what types of investments yield the best outcomes. Colleges need evidence-based information on best practices and processes that emerge from implementing AB 19 across the state. More data will be available this academic year (2019–20). The chancellor will require colleges to provide information on how they spent the funds, allowing for policy evaluation studies. We applaud this effort and invite the chancellor's office to facilitate sharing these data so researchers and institutions across the state can assist in assessing and evaluating the impact of the California College Promise.

Rios-Aguilar, C., & Lyke, A. (2020, March). The California college promise: A promise to what, for whom, and where? [Policy brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/california-college-promise