Guidance for District Administrators Serving Newcomer Students

Summary

Newcomers represent a large and understudied subgroup of students in California. The Oakland Unified School District has been disaggregating data on newcomer status for the last 7 years, providing a basis for analyzing graduation outcomes for newcomer compared to non-newcomer students. The data highlight the variance in outcomes based on program placement and design. Drawing from analysis of Oakland Unified’s data and practices, the authors make programmatic recommendations for districts with newcomer students, focusing on special considerations for different subgroups, enrollment patterns, school models, the intersection of special education and newcomer status, and effective models of English language development.

Introduction

The term newcomer encompasses a broad spectrum of students who have had very diverse experiences in their home countries and when immigrating to the United States. The term generally refers to foreign-born students in their first years of U.S. schooling, with the most common definition going back to the Title III Immigrant Students Act.1 Newcomer youth are often described by the hardships they have faced. The news cycle regularly refers to unaccompanied minors on the U.S.–Mexico border and sometimes includes feel-good stories of refugees finding new homes.2 Missing from this discourse is a data-based understanding of who newcomer students are, what their outcomes are, and how schools and school systems need to improve to support this population. This brief presents information on California newcomer students and looks at newcomer outcomes in one California school district. It suggests promising practices at the local level to support newcomer education as well as policy changes at the state level to promote better instruction and support for newcomer students.

It is important to understand that, while newcomer students share some similarities with the larger English learner (EL) population, are distinct in many key ways. They often are adapting to a very different language, culture, and school environment as well as to basic social norms. These adaptations can be immense, complicated, and fraught. The timeline for being able to adapt is short, particularly for those at the secondary level, and the stakes are high. Schools without focused resources, trained staff, and a clear vision and response will struggle to meet the needs of newcomer students.

Data on Newcomer Students in California

In California, newcomer students are not treated as a distinct subgroup in publicly accessible data and accountability systems. This absence of data on newcomers makes it challenging for education leaders, policymakers, researchers, and curriculum developers to see them as a separate and distinct group from ELs. This section presents an overview of what we know about the state’s newcomer students based on federal reporting as well as an analysis of one district that does collect data on newcomer students as a distinct student subgroup.

Macrolevel Data on Newcomer Students in California

Much of California’s data collection comes from districts requiring federal reporting for Title III, which determines immigrant student status through date of birth, place of birth, and prior school enrollment, all collected by local educational agencies (LEAs) in home language surveys. A special data request to the California Department of Education (CDE) in 2022 allowed us to analyze the 2020–21 Title III data by district. These data enabled us to form a macropicture of how many students there are and where they attend school but did not contain more granular and outcome-focused information.3 In these data we found that the number of newcomers has fluctuated between 150,000 and 200,000 students in recent years, although the number formally enrolled in programs funded by Title III has been much lower.4

Disaggregated Data on Newcomer Students in Oakland Unified School District

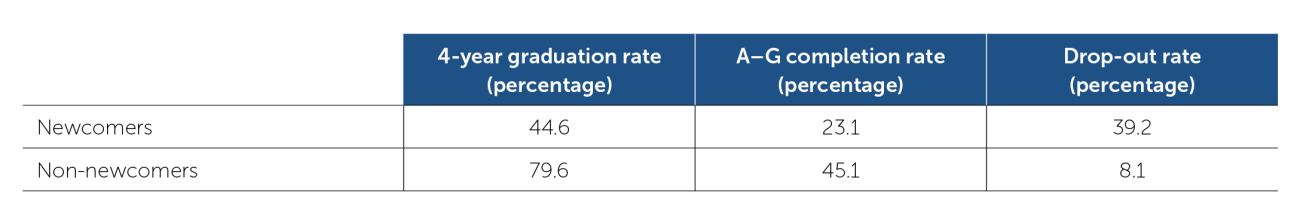

School leaders in Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) found that the lack of insight into the number and needs of newcomer students in their district was preventing them from understanding the outcomes and opportunities to provide support for these students. Since 2017, OUSD has adopted its own disaggregation practices for newcomer data that provide a clear, comparative understanding of achievement and programming for newcomer students. OUSD’s data show that between 2,900 and 3,700 newcomer students were enrolled in OUSD for each of the last 7 school years. These students have been concentrated at the high school level, with newcomers accounting for more than 20 percent of the 2020, 2021, and 2022 senior cohorts. OUSD newcomers represent higher percentages of students qualifying for free or reduced-priced meals (FRPM), students with interrupted formal education (SIFEs), and unaccompanied minors than state and national averages. Compared with non-newcomer students—in this data disaggregation, these are any students who are not Title III students—the outcomes for newcomer students are concerning. Analysis of data from 2018–22 finds dramatically lower 4-year graduation rates and A–G completion rates for newcomer students, and their drop-out rate is nearly five times that of non-newcomer students (Table 1).

Table 1. High School Outcomes of Newcomer and Non-newcomer Students (2018–22)

Note. The A–G completion rate is calculated as a percentage of the cohort, not a percentage of graduates.

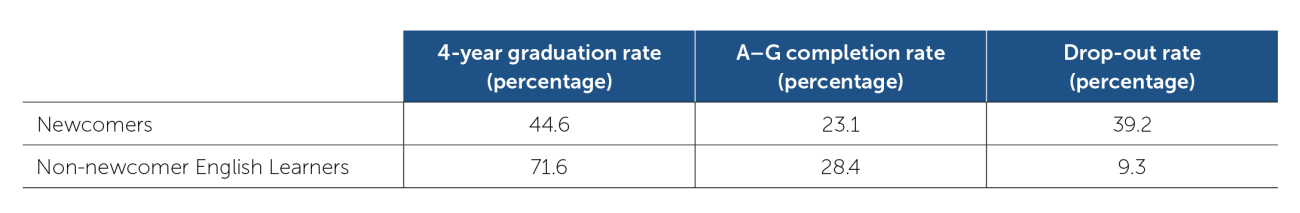

We also compared newcomers in OUSD with non-newcomer ELs (Table 2). This analysis revealed substantial differences in outcomes between the two groups, underscoring the importance of having data that distinguish between newcomers and ELs.

Table 2. High School Outcomes of Newcomer and Non-Newcomer English Learner Students (2018–22)

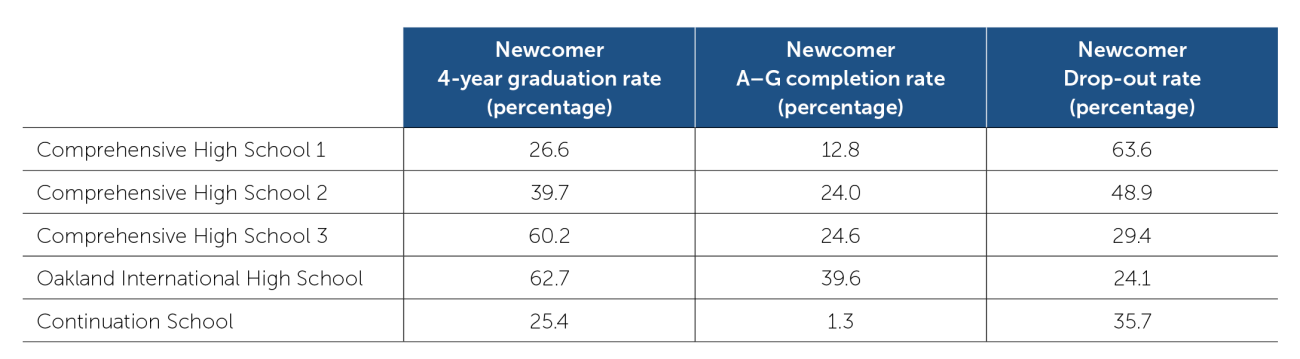

At the high school level in OUSD, there are five major newcomer hubs: three comprehensive schools with newcomer programs built within them, one specialized school specifically for newcomers, and one continuation school with a newcomer program. Table 3 presents the analysis of outcome data for newcomers in each of these schools.

Table 3. Newcomer Outcomes by High School in Oakland Unified School District (2018–22)

Note. The graduation rate and drop-out rates do not add to 100 percent as it is a 4-year graduation rate and there are still students enrolled past year 4.

Each school serves a slightly different population and has a different institutional capacity and focus. Still, there are some fundamental takeaways from this data:

- Newcomer students are much more likely to drop out and much less likely to graduate than non-newcomer students.

- Some schools have significantly higher graduation rates and lower drop-out rates than others for newcomer students.

Practice and Policy Recommendations for Newcomer Education

The findings from these analyses of disaggregated newcomer student data indicate that newcomer students are a vulnerable student group that, on average, struggles to meet common benchmarks of success at the secondary level. The findings also prompt us to explore the ways in which practices and policies at the school level may make a difference for newcomer students’ success. This section draws from best practices from OUSD to highlight promising practices for schools and districts to consider. This is in no way an exhaustive list but is meant to be a starting place for formulating concrete, practical solutions.

Tracking Newcomer Data

To serve newcomer students better, it is imperative that districts know which of their students are newcomers. A highly recommended first step for any district is to implement a system like OUSD’s to collect quantitative data. OUSD uses the following tags for newcomer data:

- N0. Midyear arrivals.

- N1. In the first full year of academic instruction.

- N2. In the second full year of academic instruction.

- N3. In the third full of academic instruction.

- FN. Former newcomer.

These tags allow any measure to be searched for and evaluated by newcomer status.5 This supports thoughtful monitoring of outcomes for newcomer students and provides input into program creation across sites.

SIFE tagging can also be extremely useful but requires agreeing on a common definition. Ideally, the CDE would supply this definition, along with a screener that has fidelity to it. A few states already have a definition and screening tools. New York’s screening tools include a SIFE interview questionnaire, a written test, a vocabulary and reading comprehension test in the student’s home language, and a math test. Using tagging and testing, schools can determine the number of SIFEs, design programs based on those numbers, and evaluate which programs are successful. Without tagging and testing provided by the CDE, a district can adopt its own practices.

Determining Grade-Level Placement

One of the first decisions a school district must make when a newcomer student enrolls is the student’s appropriate grade-level placement. Guidance for student placement differs for high school and earlier grades. Newcomers in primary and middle school should be placed according to age because research shows that English language proficiency develops rapidly among young newcomers.6

There is more to consider for newcomers at the high school level. The law is clear that all students must attend school until the age of 18. What can cause some confusion is schools’ responsibility to provide placement for any student, newcomers included, up through the age of 21.7 It should be the student’s not the school’s decision whether to continue in a comprehensive high school or specialized senior program after age 18. This is particularly important because it is recommended that newcomer students be placed at the secondary level based on incoming credits, not age.8 If districts follow this guideline, then many newcomers at the high school level will not be in an age-peer group and will not graduate by the age of 18. This is acceptable, however.

Preparing for and Supporting Midyear Arrivals

In California, districts count total school enrollment and report the number and demographics of all students enrolled on Census Day—the first Wednesday in October. This reporting is used to generate funding under the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The longitudinal data of OUSD show that about 50 percent of newcomer students first enroll after the October Census Day. The number of new enrollments tends to remain steady from the beginning of the year through December, with a spike around Christmas, and continues until summer.

The Census Day count determines apportionment of funding from the state and is often how districts decide on the size of their programs. Given newcomer immigration patterns, the Census Day count does not adequately reflect the number of newcomers who will be in a program. This results in lower funding for districts and programs serving newcomers. The lower funding level, in turn, is due to fewer supplemental and concentration funds as well as to lower average daily attendance rates because students are arriving mid-year.

There are steps districts can take under the current system to anticipate and support newcomers who arrive after the start of the school year. Schools and districts should monitor the flow of students from year to year and make projections so that programs that are staffed with veteran teachers can be designed. OUSD does this by adding the October Census Day count to the projected number of late-arriving newcomers, which enables staffing to be available as students arrive. This means that newcomer programs and classrooms that may look “overstaffed” at the beginning of the school year are anticipating additional enrollment over the course of the year. When districts do not have adequate plans, there is scrambling midyear to hire typically underqualified candidates to teach the incoming newcomers, or students are moved prematurely up an English language development (ELD) level to balance classroom numbers, exacerbating an already existing inequality in placement of teaching staff.9

Another complicating factor is that charter schools, particularly those that are sought out, do not have the ability under current law to hold open seats for incoming newcomer students. This is one of the many factors funneling newcomer students to district-run schools. In California, district schools have, as a percentage of the student body, double the number of newcomers that charter schools do.10

Selecting Academic Models

Districts with larger concentrations of newcomers can design programs to meet the needs of these students. This is particularly important at the secondary level where school design has shown a greater impact on language-growth trajectories.11 Many of the various design models are represented across OUSD high schools, including the following:

- high schools where newcomers are in ELD classes and mainstreamed into all other classes;

- high schools that have specially designed newcomer programs in the school, where early newcomers are in ELD classes as well as sheltered content classes for a limited number of years or for the entirety of high school;

- specially designed schools exclusively for newcomer students with a separate model and pedagogy; and

- continuation school programs for newcomer students.

Continuation schools are typically designed for students who cannot succeed in the traditional school pathway; they will often have a lower credit requirement and more flexibility in programming for their students.

It is important for districts to understand who their newcomer students are and how successful they are in the model that is in place. Districts need to collect data on graduation rates and hold student observations and interviews to evaluate the model’s efficacy. Districts will likely find that more support or a broader shift in the school model is required.

Although not many technical assistance models for newcomers are available, the Oakland International High School Learning Lab, which is based out of an Internationals Network school, is intended to be a resource for schools that want to serve their newcomer students better. The Internationals Network specializes in opening schools for newcomer students and has strong empirical data behind its model.

Supporting English Language Development

The primary thrust of any newcomer programming is English language development. What we know from newcomers is that they will, on average, come into U.S. schools with lower English proficiency than their non-newcomer EL peers, but they will show fast growth over the initial 2 years of language development. These 2 years are critical for providing support. While the English levels of incoming high school newcomer students are on average higher than those of middle and elementary newcomer students, the rate at which these students acquire English is slower in upper than it is in lower grades.12

- Content language integration. In this model, teaching English becomes the duty of all teachers. Rather than English language development being siloed, it is thoughtfully planned throughout all content classes.13

- Pedagogy with meaningful access to rigorous content curriculum. Newcomers, particularly at the secondary level, will not be able to use traditional textbooks or course materials for subject areas. To assure the greatest language and academic growth, teaching grade level standards while differentiating support for language is required.14

- Learning environments welcoming to translanguaging and multilingual responses to learning. A welcoming translanguaging environment is one in which both English and home languages are used intentionally to support learning and accelerate language acquisition and content growth.15

- Productive and intentional academic peer interaction. Newcomer students who rely on their peers and get lateral support will have better social-emotional outcomes, including connectedness to school, and will be more likely to persist in school and advance academically. These interactions can be fostered in classes.16

Sequencing Courses and Supporting Credit Recovery

Newcomer students often arrive midyear, and it is common for their transcripts to have course gaps or courses that do not line up with sequences in the districts where they enroll. Schools need to have a clear plan for coursework remediation. Common recommendations for newcomer course remediation include:

- summer school for both credit recovery and ELD;

- schedule flexibility with multiple opportunities for credit recovery as well as experienced teachers leading high-needs classes;17

- corequisite course options to support SIFEs in high-leverage classes (this is not yet well researched but could follow the data on corequisite models at the collegiate level);18 and

- courses leveraged to fill credit needs, such as using ELD 5 to fill gaps in English Language Arts 1 and 2.

Implementing Assembly Bill 2121

Assembly Bill (AB) 2121, which was extended to include newcomers in September 2018, gives newcomer students the opportunity to have their graduation requirements reduced to the state minimum, 130 credits, if they are too far off track to graduate with their cohort using the district’s credit requirements.19 This law can be planned for and built into a district’s response to newcomer students’ needs.

Providing Alternatives to Foreign Language Requirements

A typical district graduation requirement is that students have foreign language credits. For newcomer students who are already actively developing multilingual proficiency, the requirement to show proficiency in yet another language through a high school class can be excessively burdensome. As an alternative, either home country school transcripts or Languages Other Than English (LOTE) equivalency exams can be used to demonstrate foreign language proficiency. LOTE tests can be administered at the school site or district level. If a student’s native language is one for which a district does not yet have a test, a district can approve a third-party examination to validate linguistic proficiency in that language; this practice should be considered for newcomers with minority languages.

Identifying Newcomer Students with Disabilities

It is uncommon for newcomers to have special education (SPED) needs identified in such a way that an Individualized Education Program and services can start immediately. In OUSD, the rate of SPED newcomer identification from 2016–22 was between 2.5 and 4.5 percent, compared with the overall identification rate of between 13.1 and 16.4 percent. The rate for secondary newcomer students was significantly lower at 0.8–2.7 percent. Similar trends in newcomer SPED identification were found in a two-state research study that showed SPED identification rates for newcomers at between 2.8 and 3.4 percent compared to between 12.9 and 14.4 percent for non-newcomers in those states.20

Underidentification of newcomers’ SPED needs poses many challenges:

- Students do not receive the needed supports for learning.

- Schools with large newcomer populations receive fewer district-supported services (i.e., fewer bilingual paraprofessionals, parent liaisons, and resources for teachers).

- Students, particularly at the secondary level, will never be identified and will lose out on services to travel with them past high school.

- Students are at an elevated risk for dropping out of school.

- Schools and districts put themselves at risk under the Child Find laws and leave themselves vulnerable to lawsuits.

Recommendations for the State

California sits at a unique nexus. It is the largest and most linguistically diverse education system in the country. Newcomer students represent a large and varied student subgroup. To provide them with the greatest access to learning, changes at the school, district, and state level are recommended. In 2017, California allocated funding for the California Newcomer Education and Well-Being (CalNEW) program, which gives LEAs funding for direct services to refugee students and other eligible school-aged children to improve their well-being, English-language proficiency, and academic performance. CalNEW, which currently receives funding of $5 million per year and serves 21 districts, is the only newcomer-specific state funding available for schools. In this section, additional changes at the state level are recommended to support instruction of California’s newcomer students. These recommendations fall into three general categories: definitions and data, technical assistance, and funding.

Definitions and Data

Newcomer data tag. As a first step, the state should come up with a data-tracking system that can be searched by newcomer status. This system should be included in the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS) and have the newcomer tags N0, N1, N2, N3, and FN so that all measures can be evaluated on their effectiveness for newcomers.

SIFEs. The state should adopt a formalized definition of a SIFE as well as a unified way to identify SIFEs, curricular resources, and targeted funding to support the additional services those students need to be more successful in school. This effort could be made in partnership with the New York State Education Department, which has already taken many of these steps.

Unaccompanied minors. The state could make the following improvements:

- Create a codified status within state data systems for unaccompanied minors, with the express intent of helping those students to graduate high school and remain in the country; the status would include an increase in targeted funding, enabling schools and nonprofit legal aid organizations to partner in providing legal representation in deportation proceedings.

- Cooperate with the Office of Refugee Resettlement on connecting students and their sponsors with the school district on release from detention.

- Develop a structure similar to, though not explicitly connected to, youth in foster care, allowing those who house unaccompanied minors to receive some compensation.

English language assessments. Understanding of newcomer growth related to the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC), particularly for secondary newcomer students, is needed. With this nuanced understanding, added support for curricula, technical assistance, and finances should be considered for students who are identified as being in the first level of ELPAC.

Update and clarify California Education Code § 46300.1. As currently written, it can be unclear to schools what responsibilities they have for students aged 18–21. Schools should receive clearer guidance on the need to provide opportunities to graduate even for students over the age of 18.

Technical Assistance

A level of technical assistance for schools and districts serving newcomer students should be adopted through the CDE, ideally working with County Offices of Education to provide expertise and guidance.

Community schools and block grants. The State Transformational Assistance Center for Community Schools could partner with newcomer-specific agencies to provide training on supporting the whole child as pertains to newcomers. This training should cover many of the specific needs newcomers face and be delivered to administrators and staff supporting community school initiatives.

Curricula. The CDE could support development of curricula for SIFEs at a secondary level in ELD courses and math. Additional curriculum development for sheltered content classes for newcomers is also appropriate.

Funding

LCFF. The state should rework the LCFF to provide additional funding for students who sit in multiple nonduplicative multipliers.

ADA. Districts should hold open fully funded seats for expected newcomers so that the most recent arrivals can enter thoughtful, well-staffed programs. To achieve this, the ADA funding model needs to change, or supplemental funds need to be provided to cover the costs.

CalNEW Grants. The state should expand CalNEW grants to include more dollars and more LEAs receiving those dollars. Ideally, any district receiving a significant level of newcomers could qualify for the grant. The grant recipients should serve in a community of practice for the state that tests and endorses educational theory on newcomers.

Conclusion

Serving newcomer students represents a unique opportunity for any school, district, or state. Although data collection systems, student supports, and pedagogy are nascent for newcomers, they have shown that focused programming and state resources can effectively move the needle on outcomes. As educators and policymakers, it is our responsibility to work collectively and in community with our newcomer students and families.

This publication is part of a series on newcomer education in California that was produced by the PACE Research–Practice–Policy Partnership on Newcomer Education. Additional publications in the series appear under "Related Publications" on this page.

- 1U.S. Department of Education. (2016, September). Newcomer tool kit. www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oela/new-comer-toolkit/ ncomertoolkit.pdf

- 2Montoya-Galvez, C. (2022, October 14). Nearly 130,000 unaccompanied migrant children entered in the U.S. shelter system in 2022, a record. CBS News. cbsnews.com/news/immigration-unaccompanied-migrant-children-record-numbers-us-shelter-system

- 3Finn, S. (2023, May). Newcomer education in California [Report]. Policy Analysis for California Education. edpolicyinca.org/ publications/newcomer-education-california

- 4California Department of Education. (2022). Title III Immigrant Student demographics. cde.ca.gov/sp/el/t3/imdemographics.asp; for additional analysis of this data, see Finn, 2023.

- 5For example, on the public OUSD graduation page, graduation rates can be viewed by site and newcomer status; see https://dashboards.ousd.org/views/CohortGraduationandDropout_0/Comparison?%3Aembed=y&%3AshowAppBanner=false&%3Adisplay_count=n&%3AshowVizHome=n&%3Aorigin=viz_share_link&4

- 6Umansky, I. M., Thompson, K. D., Soland, J., & Kibler, A. K. (2022). Understanding newcomer English learner students’ English language development: Comparisons and predictors. Bilingual Research Journal, 45(2), 180–204. doi.org/10.1080/ 15235882.2022.2111618

- 7Cal. Education Code § 46300.1 (1993).

- 8Washington Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (2022). Newcomer students. https://k12.wa.us/sites/default/files/public/migrantbilingual/pubdocs/08NewcomerStudents[1].pdf#:~:text

- 9Adamson, F., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2011, December). Addressing the inequitable distribution of teachers: What it will take to get qualified, effective teachers in all communities [Research brief]. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/addressing-inequitable-distribution-teachers-what-it-will-take-get-qualified-effective-teachers-all-_1.pdf - 10Finn, S., 2023.

- 11Umansky et al., 2022.

- 12Umansky et al., 2022.

- 13Villabona, N., & Cenoz, J. (2022). The integration of content and language in CLIL: A challenge for content-driven and language-driven teachers. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 35(1), 36–50. doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2021.1910703

- 14Kibler, A. K., Walqui, A., & Bunch, G. C. (2015). Transformational opportunities: Language and literacy instruction for English language learners in the Common Core era in the United States. TESOL Journal, 6(1), 9–35; Lang, N. W. (2019). Teachers’ translanguaging practices and “safe spaces” for adolescent newcomers: Toward alternative visions. Bilingual Research Journal, 42(1), 73–89; Walqui, A., & Bunch, G. C. (2019). What is quality learning for English learners? In A. Walqui & G. C. Bunch (Eds.), Amplifying the curriculum: Designing quality learning opportunities for English learners (pp. 21–41). WestEd.

- 15Poza, L. E. (2018). The language of ciencia: Translanguaging and learning in a bilingual science classroom. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(1), 1–19. doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1125849; Ramirez, P. C., & Salinas, C. (2021). Reimagining language space with bilingual youth in a social studies classroom. Bilingual Research Journal, 44(4), 409–425. doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2021.1994054

- 16Carhill-Poza, A. (2015). Opportunities and outcomes: The role of peers in developing the oral academic English proficiency of adolescent English learners. The Modern Language Journal, 99(4), 678–695; Kibler et al., 2015.

- 17Chenoweth, K. (2016). ESSA offers changes that can continue learning gains. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(8), 38–42. doi.org/10.1177/0031721716647017

- 18Scott-Clayton, J. (2018, March 29). Evidence-based reforms in college remediation are gaining steam and so far living up to the

hype [Report]. Brookings. brookings.edu/research/evidence-based-reforms-in-college-remediation-are-gaining-steam-and-so-

far-living-up-to-the-hype - 19Assemb. B. 2121, Chapter 581 (Cal. Stat. 2018). leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB2121

- 20Thompson, K. D., Umansky I. M., & Porter, L. (2020). Examining contexts of reception for newcomer students. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 19(1), 10-35. doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2020.1712732

Hansen, D. & Finn, S. (2023, June). Guidance for district administrators serving newcomer students [Policy brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/guidance-district-administrators-serving-newcomer-students