Effects of Immigration Enforcement on Students in California

Summary

This study examines the associations between county-level immigration arrests and academic achievement, absenteeism, and measures of school climate and safety for students in the California CORE districts. We found consistent evidence that Latinx and Latinx English learner (EL) students experienced declines in academic achievement, attendance, and perceptions of school climate and safety when there were more immigration arrests in the counties where their schools were located. These relationships were strongest for arrests that occurred during the Trump administration compared with those that occurred during the second term of the Obama administration. We discuss the implications of our findings and offer suggestions for policies and practices that schools and districts could implement to create safer, more welcoming environments for their immigrant-origin students and families in the face of anti-immigrant actions.

Introduction

In California, a state of 10.6 million immigrants, 2.2 million immigrants are undocumented, roughly 125,000 of whom are children under the age of 16. One in five U.S. citizen children in California, or 1.7 million young people, lives with at least one undocumented family member. Consequently, immigration policies and enforcement as well as anti-immigrant actions can powerfully influence the lives of millions of students in the state.

Immigration enforcement has significant, long-lasting consequences for undocumented immigrants and their children. Immigration-related arrests and deportations contribute to income, housing, and childcare instability. In addition, children of undocumented parents have higher rates of mental health issues, lower rates of preschool enrollment, and less access to medical care than their peers.

The negative effects of immigration-enforcement activity, restrictive immigration policies, and anti-immigrant rhetoric extend far beyond families with undocumented immigrant members. Studies of immigration-enforcement effects have found high associations between immigration enforcement and school mobility, decreased academic performance, and declining social-emotional well-being among Latinx students generally, regardless of their or their families’ status.

To date, few studies have analyzed the effects of the Trump administration’s implementation of harsher enforcement tactics and restrictive immigration and asylum policies on student outcomes. In this brief, which is based on a study published in AERA Open, we describe the association between immigration enforcement and educational outcomes for students in seven of the eight California CORE districts—the eight largest school districts in California, collectively serving more than one million students. Using data spanning the 2014–18 school years (from President Barack Obama’s second term through the first year and a half of President Donald Trump’s administration), we examined how changes in county-level immigration arrests by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) occurring under distinct national political contexts related to changes in students’ math and English language arts (ELA) achievement and absenteeism. We also show how students’ perceptions of school climate, supports for academic learning, sense of belonging, lack of school safety, and bullying changed under different immigration policy contexts and enforcement rates.

Policy Context

When President Trump took office in January 2017, he launched an aggressive, systematic policy agenda to block migration and asylum seeking to the United States, limit the rights of immigrants and their dependents, and pursue large-scale detention and deportation of immigrants. Despite the record-breaking rates of deportation that occurred under Obama’s presidency, the Trump administration’s approach signaled an embrace of more widespread immigration enforcement that would be expanded through numerous policies and actions as well as vociferous anti-immigrant rhetoric throughout his presidency.

With the passage of the California Values Act (Senate Bill 54) and its implementation beginning in January 2018, California became a “sanctuary state.” This law prohibited the use of state or local resources to assist federal immigration enforcement, and schools, hospitals, and courthouses were designated “safe spaces” from which ICE agents were barred. Police officers and sheriffs were also forbidden from asking individuals about their immigration status, arresting them on the sole grounds of having a deportation order, or sharing personal information like home addresses with ICE or the U.S. Border Patrol (unless publicly available). Despite this state law, high levels of federal immigration activity have been sustained in the state. For example, more than 30,000 people were deported from California during the 2019 fiscal year, and a record 80,000 deportation proceedings were filed in California immigration courts that same year for individuals without felony, national security, terrorism, or other criminal charges.

In the counties served by the CORE districts, the number of immigration arrests varies by county and over time. We compiled data from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse examining the number of arrests that occurred during the school year from 2014–15 to 2017–18. Los Angeles County had the greatest number of immigration arrests consistently each year, although the number of arrests declined from 2014–15 to 2015–16 and then slightly increased during the following school years. The other four counties had an increase in the number of immigration arrests from 2014–15 to 2015–16, with Sacramento and Alameda Counties experiencing increases each subsequent year.

Finding 1: Achievement, Attendance, and School Climate and Safety Decline for Latinx and Latinx English Learners as Immigration Arrests Increase

We compared changes in academic and nonacademic measures during periods with greater and fewer incidents of immigration arrests. In our analysis, we found consistent evidence that Latinx and Latinx English learner (EL) students experienced declines in achievement, attendance, and perceptions of school climate and safety when more immigration arrests occurred in the counties where their schools were located. Of all the student populations we examined, evidence of immigration-enforcement effects is most consistent for these two subgroups. These measures did not decline for non-Latinx students (White, Black, and Asian American students) as immigration arrests increased.

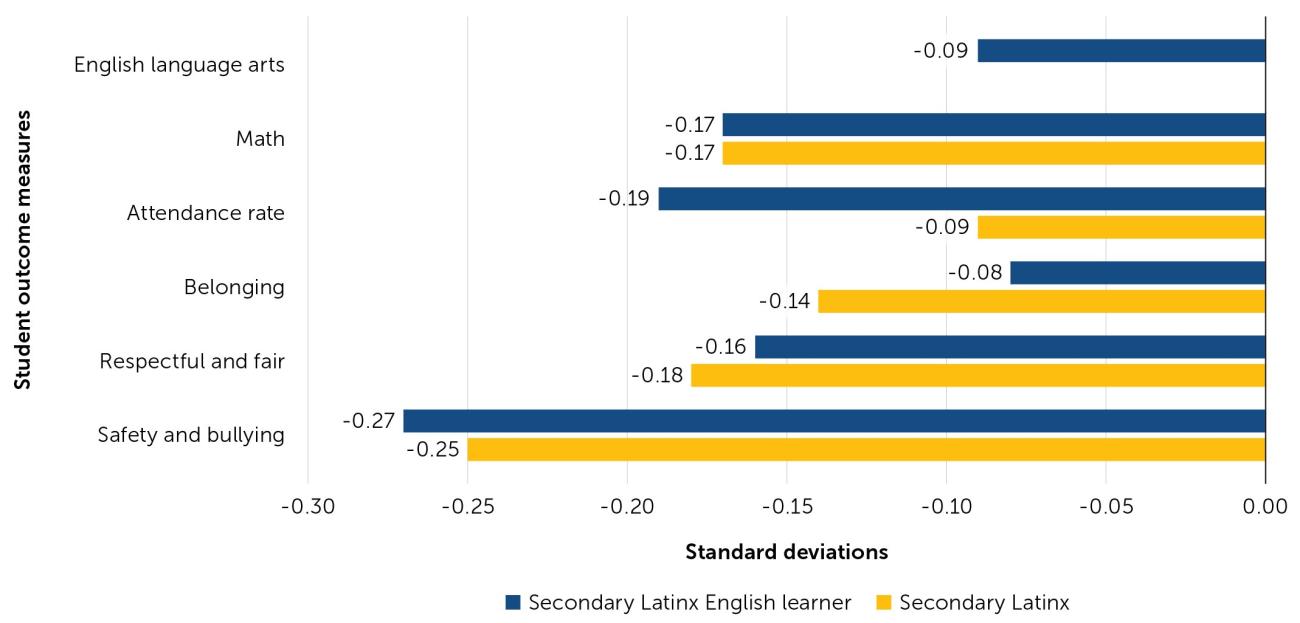

We examined outcomes for elementary and secondary students separately, where secondary refers to students in sixth grade and up. Figure 1 illustrates the magnitude of the changes in academic and nonacademic measures for Latinx and Latinx EL secondary students for every one standard deviation of immigration arrests scaled by the percentage of the county-level population that is foreign born. Consistent with previous research, we scaled the number of immigration arrests by county foreign-born population to account for some counties being larger than others and having more immigrant-origin inhabitants. For example, a standard deviation of immigration arrests in Sacramento County is approximately 500 arrests, whereas for Fresno County this number is approximately 350.

Figure 1. Declines in Educational Outcomes With Increases in Immigration Arrests

When immigration arrests increased, secondary Latinx students reported more incidents of bullying or experiencing a lack of safety, felt less of a sense of belonging, experienced declines in school attendance, and had lower achievement in math. Figure 1 shows these declines in standard deviation units so that the magnitude of the associations can be compared across outcomes. The largest declines in students’ outcomes were observed for sense of safety and bullying.

We observed greater declines for Latinx ELs for several of the measures, including perception of school safety and attendance rates. We did not find a link between immigration arrests and ELA scores for Latinx students but found that immigration arrests did relate to declines in ELA scores for Latinx ELs. Using rough conversion estimates from other researchers, the declines in achievement equal a loss of two months of learning in math and one month of learning in ELA for Latinx ELs. This also translates into two additional days of absence for Latinx ELs. When examining results for Latinx EL elementary students, we found slightly smaller yet still meaningful evidence of declines in math, ELA, and attendance with increases in immigration arrests. We did not find evidence of a relationship between immigration arrests and non-EL Latinx elementary student outcomes.

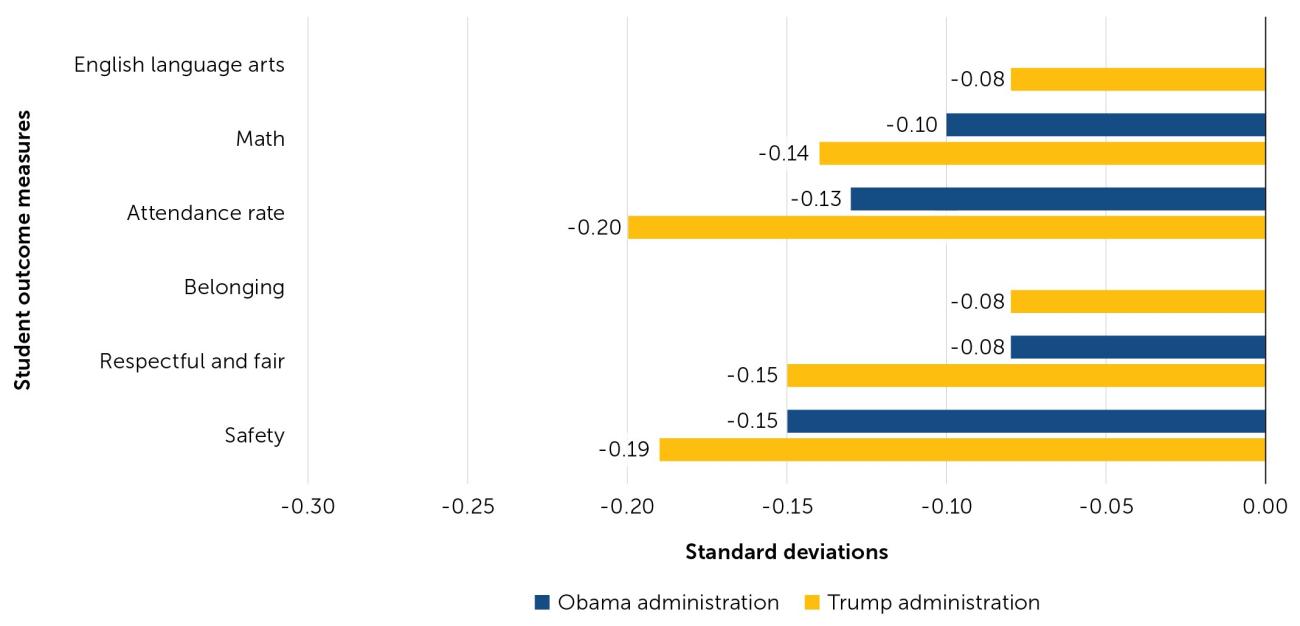

Finding 2: Declines Related to Immigration Arrests Were Sharper During the Trump Administration

Our analysis found that the strength of the association between immigration arrests and students’ academic and nonacademic outcomes was greater in the years when Trump was president. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the magnitude of these findings for secondary and elementary students, respectively. Comparing the yellow and blue bars for each outcome individually, the associated impacts from immigration arrests to student outcomes were more consistent and stronger during the Trump administration. Most notably, the association between immigration arrests and perceptions of secondary Latinx EL students that their teachers and schools were respectful and fair was twice as large when arrests occurred under the Trump administration compared with arrests that occurred under the Obama administration. An increase of one standard deviation in immigration arrests during the Trump administration was associated with absences of approximately two and a half days, compared with one and a half days under the Obama administration.

Figure 2. Impacts of Immigration Enforcement on Secondary Latinx English Learners’ Academics, Attendance, and Perceptions of School Climate and Safety

Figure 3. Impacts of Immigration Enforcement on Elementary Latinx English Learners’ Academics and Attendance

The differences in magnitude of these findings suggest that heightened immigration enforcement effectuated in a national context of expanded xenophobic rhetoric may be tied to strong and pervasive educational damage for Latinx EL students.

Discussion

Our results identify several important patterns associated with immigration arrests, including evidence of worse outcomes for students when arrests occur under a more vocally xenophobic president who removed deportation protections for noncriminals. Our findings confirm prior research documenting educational penalties that accompany heightened enforcement activity for Latinx students. The totality of the consequences stemming from school absences driven by immigration arrests remains to be seen, but students tend to suffer when they are not consistently attending school, and immigration-enforcement activity and threats have interrupted many students’ regular attendance patterns and ability to learn effectively even when in school.

Our significant findings for the negative effects of nearby immigration-enforcement activity on students’ math scores is consistent with earlier work and aligns with evidence showing that math achievement tends to be most affected by disruptions to the learning context. Because math instruction tends to be sequential, requiring students to build on concepts and theories taught in prior weeks, missing multiple days of school or being unable to grasp or retain complex information—even for a short period of time—may produce greater learning gaps.

Finally, our results underscore the powerful implications that immigration enforcement may have for multiple aspects of a school’s culture and climate, ranging from students’ perceptions of fairness and respect to their experiences of bullying as well as their sense of safety and belonging. In this way, our findings demonstrate how immigration enforcement can function as an act of community violence—i.e., an event that produces individual- and community-level trauma—that penetrates deeply into the educational lives of immigrant-origin youth and their peers. Our data show that a broad swath of the student body—not just those students whose family members are directly targeted by ICE—perceive negative changes in the feeling and functioning of a school when enforcement activity rises. Therefore, this study provides an example of the value of using a wider analytic lens to measure the consequences of immigration enforcement both empirically and theoretically through the framework of a pyramid of enforcement effects.

Recommendations

Here we present research-based practices that have shown promise for creating safe, welcoming school environments for vulnerable students, including immigrant-origin students confronted with immigration enforcement and anti-immigrant policies, practices, and rhetoric. We also suggest avenues for further research to better understand what schools and school districts can and are doing to make schools safe spaces for students and families affected by immigration enforcement.

Implement Inclusive and Supportive Policies and Practices for Immigrant-Origin Students

For students to perceive schools as safe, they must feel confident that they will be protected against physical and emotional violence that could negatively affect their well-being. Inclusive policies that consider immigrant-origin students’ needs, including those related to immigration status and enforcement, may help establish the necessary foundation for creating secure, welcoming environments.

Implement and enforce policies against racism, xenophobia, sexism, homophobia, and other forms of oppression. All schools should have clear, stringently enforced policies that address any forms of bullying, harassment, and assault. These must be accompanied by comprehensive training for school personnel tasked with enforcing the policies and well-articulated expectations of their responsibility to intervene when incidents of victimization occur. Researchers at GLSEN (formerly the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network) found that having such policies, along with their systematic enforcement, is strongly associated with positive reports of belonging, safety, and behavioral and academic engagement from lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) students.

Limit barriers to access and ensure confidentiality and privacy protections are enforced. Schools should eliminate any potential obstacles that may dissuade students or their families from participating in educational activities or availing themselves of school resources. For example, districts should minimize identification requirements for school enrollment, participation in any school-related programs, or borrowing district-issued equipment. Additionally, districts should adhere to the California Department of Education’s strict policies on student privacy and should widely publicize their efforts to protect personal data and avoid disclosing contact information.

Allow for flexible modes of learning in times of heightened insecurity. Increased student absenteeism is one of the multiple educational consequences associated with nearby immigration-enforcement activity. Policies that allow students to continue to access educational content and instruction via remote learning options under special circumstances such as ICE activity in the community would prevent unnecessary loss-of-learning opportunities. Virtual and hybrid learning formats and policies developed during the COVID-19 pandemic may offer models for how to successfully engage students who may temporarily be unable to attend in person because of these disruptions.

Adopt inclusive curricula and in-school practices. There is abundant evidence of the importance of relevant, meaningful learning opportunities for students of all backgrounds to foster sustained academic engagement, cross-cultural learning, and achievement. Efforts to ensure that students see themselves and their families reflected in curricular materials, school-wide events, speakers, and school personnel should attend to all aspects of young people’s identities, including their families’ histories, cultures, languages, ethnicities, races, gender identities, and migration experiences. Thoughtful, deliberate decision-making about what is taught in classrooms and what messages are being communicated in the school building about who belongs can powerfully affect how immigrant-origin (and other) student populations feel in and about their schools.

Show “visible displays of support” for immigrant-origin students and communities. GLSEN has documented the power of “visible displays of support” for improving school climate, sense of safety and belonging, and school engagement and performance for LGBTQ+ students. Schools should commit to demonstrating support for immigrant-origin students and communities explicitly or “signaling affirmation” and can do so in a number of ways: (a) visual, public displays, such as signs and posters; (b) written forms of affirmation, such as emails of support from administration; and (c) verbal affirmation from educators who speak directly to students in classrooms. All have been shown to have a positive influence on students’ sense of belonging and acceptance in school.

Implement Inclusive and Supportive Practices for Immigrant Families

Ensure access to adequate translation and interpretation services. Despite federal and state laws mandating that school districts provide education-related information to families in languages that they understand, serious obstacles still exist. At a minimum, schools should guarantee that family members have access to appropriate translations and, when necessary, interpretation services when they attend school events, interact with school personnel, and receive any information about their children’s education. These services should be well advertised in multiple formats and outlets so that families know they exist and see their children’s schools making concerted efforts to engage with them.

Provide information to immigrant families about legal and educational rights and services. To foster stronger ties with immigrant families, districts should provide information about immigrants’ legal and educational rights and direct them to available services and supports. This may include hosting legal workshops and “know your rights” events and serving as a liaison between families and community members with resources and expertise in these areas. School districts can also affirmatively demonstrate their commitment to inclusion of undocumented students and families through visible messages and outreach as well as by reducing the complexity and demands of school-enrollment procedures.

Training and Support for School Personnel

Principals, teachers, social workers, school psychologists, and other personnel working in classrooms have daily direct contact with students living in a national context of restrictive immigration policies, enforcement, and xenophobia. As a result, they may be best positioned to identify and respond to students who are experiencing the detrimental effects of these harmful policies. Yet school personnel are rarely taught about immigration policies and immigrants’ rights or trained to address the consequences of students’ immigration-related fears, anxiety, and trauma.

Districts with large immigrant-origin student populations should mandate trainings that include basic information about immigrants’ rights (including, for example, the Supreme Court ruling in Plyler v. Doe that guarantees all students a right to free, basic K–12 public education regardless of legal status), publicly available services (e.g., Medi-Cal), and district and school policies that protect students’ and families’ privacy and ensure their safety in and around the school building. Given the extent of the trauma that many students experience stemming from immigration enforcement, migration journeys, family separations, living with legal uncertainty, or other related challenges, school personnel should be trained in trauma-informed educational practices and care. Finally, for immigrant-origin students to thrive, districts must know about and take seriously anti-immigrant hate and oppression as well as prepare school personnel to intervene in the face of discrimination. District and school leaders should train staff to respond to victimization, racism, and any forms of bias and discrimination—including anti-immigrant hate—and emphasize educators’ responsibilities to intervene when such incidents occur. In doing so, they will demonstrate to all members of the school community that creating and maintaining a welcoming environment for all students is a priority.

Directions for Future Research

The findings presented in this brief, along with the suggested policies and practices, lay the foundation for important new directions for research. First, there is a need for more case studies that examine whether and how schools have implemented any of the recommended or other practices to create supportive environments for families that may have been affected by ICE activity. Finally, researchers should explore district and school leaders’ preparedness to address immigrant families’ needs and identify knowledge and resource gaps to facilitate improved supports for school personnel and families in these critical areas.

Sattin-Bajaj, C., & Kirksey, J. (2022, October). Effects of immigration enforcement on students in California [Policy brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/effects-immigration-enforcement-students-california