English Learners' Pathways in California’s Community Colleges Under AB 705

Summary

California’s Assembly Bill 705 has affected the way that English learners (ELs) access English and English as a second language (ESL) coursework, requiring that degree- or transfer-seeking students have the right to enroll in English or ESL courses, and community colleges are responsible for implementing initial placement practices and designing curricular structures that maximize gateway English completion. We found that ELs who graduated from a US high school and then enrolled in a community college experienced much higher throughput rates when allowed to enroll directly in transferable, college-level English composition than if they were directed to the ESL Pathway. We provide recommendations for community colleges to (a) improve placement for this subgroup of ELs, (b) integrate English support into academic instruction throughout college-level courses, and (c) better track the academic pathways of ELs from high school to college in administrative data sets.

Introduction

In October 2017, California’s Assembly Bill 705 (AB 705) required that community colleges maximize the probability that students complete transfer-level English and math. This bill aimed to ameliorate assessment and placement practices that have disproportionately contributed to inequitable outcomes for historically marginalized communities.1 AB 705 has affected how students access English as a second language (ESL) and English coursework at the community college (CC). While students can elect to enroll in ESL courses, those with a US high school cumulative grade point average (GPA) must, by default, receive placement into a gateway college-level transferable English class, with the GPA determining if that placement is with or without additional corequisite support. Additionally, CCs are responsible for providing placement practices and curricular structures that maximize the probability of completing gateway English. As a result, CCs have reconsidered whether their practices, policies, and structures were conducive to maximizing throughput rates, which is the proportion of student cohorts who complete key gateway courses (e.g., transferable, college-level English composition) in a timely manner.

There are varying perspectives on how colleges can best support student success under AB 705. The discourse around AB 705 has focused on how reliable and valid traditional methods and perspectives of placing students into English or ESL courses are; the extent to which curricular structures, including multiple levels of developmental courses, were positively affecting students’ likelihood of gateway English coursework; what kind of supports (e.g., corequisite courses) and services students would need to be successful to complete gateway English; and which students should be encouraged to begin directly in gateway English. In response to AB 705 and in hopes of maximizing throughput rates, colleges have increased access to gateway English courses by minimizing the number of prerequisite English/ESL courses and through direct placement into gateway English. Naturally, English learners (ELs) are affected by such policies.2 This brief will explore the extent to which a subgroup of ELs, those who are US high school graduates, could benefit from the resulting CC structural reforms in place under the context of AB 705.

Nowhere in the United States have educational issues concerned with ELs been more pressing and significant than in California, where linguistically minoritized students comprise nearly 40 percent of all K–12 students and an increasing population of postsecondary students.3 Recent data show that out of more than six million California public school students, approximately 1.15 million are ELs, and 200,000 are long-term English learners (LTELs); nearly 46 percent of all ELs in Grades 6–12 are LTELs.4 Another 130,000 students are considered at risk of becoming LTELs.5 ELs in California represent 18 percent of the K–12 population, with a significant proportion of EL students (more than 82 percent) being Spanish speakers.6

Regrettably, ELs remain among the most underserved in the state with respect to K–12 academic performance, reclassification, and college readiness as well as college persistence and completion.7 Consequently, many ELs and LTELs have historically started their higher education journeys in CCs with a high probability of beginning in developmental coursework. Developmental courses are neither degree-applicable nor transferable, which means that students enrolled in these sequences must persist through a greater number of classes and terms, leading to delays, increased opportunities for attrition, and, consequently, a decreased likelihood of degree attainment.8 As they transition from K–12 education to college, many ELs develop their English language proficiency, becoming bilingual or multilingual.9 Unfortunately, despite the well-supported claim that English language development (ELD) and rigorous academic preparation for college can happen at the same time, English language acquisition is instead often treated as a prerequisite to accessing college-level preparatory content.10

Recent research has clearly documented ELs’ limited access to rigorous academic instruction in middle and high school.11 By the time EL students reach CCs, many require both language and academic support because they did not have sufficient opportunity in high school to acquire the skills and knowledge necessary for a smooth transition to college. To successfully transition EL students to college, both high schools and colleges must understand the unique challenges EL students face and increase their access to the classes and support mechanisms that provide them with the confidence and skills to succeed in college. Absent a supportive environment in high school, simply providing access to college may not translate into persistence and successful completion.

Many ELs aspire to attain a bachelor’s degree. Many of these students elect to enroll in a CC as the first step on their journey, planning to eventually take advantage of transfer opportunities. Using Education Longitudinal Study of 2002 data, Kanno and Cromley found that 58 percent of ELs in tenth grade aspired to go to four-year colleges, compared to 75 percent of native English speakers and 71 percent of English-proficient language minority students.12 Furthermore, as they point out, moving from aspirations to actual enrollment in four-year postsecondary institutions is quite a challenge, particularly for ELs. Their analyses show that among the ELs who aspired to attend a four-year college, took the academic courses to qualify for admissions to a four-year college, and graduated from high school, only 62 percent applied to four-year colleges—compared to 80 percent of native speakers and 76 percent of English proficients.13

It is estimated that at least 25 percent of California CC students are ELs and immigrants.14 Because their affordability and open enrollment policies provide potential access to higher education for groups that have long been underserved by K–12 schools, California’s CCs play a potentially critical role in reducing the disparity in educational attainment between racial and ethnic groups. Furthermore, California’s CCs play a central role in educating students who are not yet fully proficient in English.15 CC ESL programs serve a large and diverse mix of students, including young adults who attended California’s K–12 schools; some were considered LTELs, some were reclassified as fluent English proficient, and others were never classified as ELs in high school. These young adults also include immigrants with high school, college, or graduate degrees from their home countries and working-age immigrants in California’s labor force.16 Evidence suggests that realizing the potential of EL students can increase the quantity and quality of human capital in the US and prepare these students to become more active participants and contributors to a healthy democracy and government.17 For example, Rumbaut found a positive relationship between bilingualism and academic as well as employment outcomes in their analysis of Southern California.18 In an increasingly competitive and global economy, EL students have the potential to meet labor market needs in critical areas that would benefit from multilingual employees.19

Even with the growth of the EL student population, there is limited knowledge regarding the academic trajectories, college experiences, and outcomes (both academic and occupational) of ELs at CCs (see box below: Four Reasons for Lack of Scholarship of ELs in Higher Education). However, now more than ever, it is essential that California fills the gap of knowledge regarding the academic and occupational outcomes of ELs. To bridge the research of ELs transitioning to college, this brief offers insights into the academic pathways of a subgroup of ELs in California’s CCs: those students who graduated from US high schools and who subsequently enrolled in CCs. We aim to describe and predict their chances of completing a degree and transfer requirements within a given time frame, as stipulated by current legislation (i.e., AB 705).

Current Policy Context in California for ELs in CCs

In California, AB 705 sought to increase access to transfer-level English and math within the California CCs.20 Signed in October 2017 and officially in effect as of January 1, 2018, the legislation was in response to a history of unnecessarily placing students into “remedial courses that may delay or deter [students’] educational progress” and the inequities that resulted from such practices, such as the disproportionate placement of students of color into the lowest levels of remediation. For example, in a statewide analysis of all first-time California CC students in 2019–20 who attempted at least one math or English course within six years, 87 percent of the students identified as Black or Latinx and 86 percent of the students identified as economically disadvantaged took at least one remedial math or English course.21 Students from historically marginalized communities were disproportionately placed in remedial education, even among students classified as “college ready.” As such, AB 705 required, by fall 2019, that all California CCs “maximize the probability that a student will enter and complete transfer-level coursework in English and math within a one-year time frame” and that colleges use high school information (coursework, grades, and GPA) to guide placement policies. According to the California Code of Regulations Title 5, such language and guidelines apply to all students who have obtained a US high school diploma or equivalent.22

Four Reasons for Lack of Scholarship of ELs in Higher Education23

- While the K–12 system has policies and procedures to classify ELs and measure their outcomes, state and federal policies do not mandate that higher education institutions identify or monitor the progress of ELs.24

- EL status can change over time as students’ English language proficiency develops; consequently, the label is dynamic. In K–12 education, once ELs meet certain academic and English proficiency thresholds, they are reclassified as fluent English proficient and exit the ELD program.25 Unfortunately, while postsecondary institutions typically collect demographic data about students, they do not systematically track each student’s language proficiency, making it virtually impossible to adequately capture or describe students’ English language proficiency.26

- Multiple terms have been used to describe EL students in higher education. Over time, the use of the various labels can make it difficult to define and distinguish EL students from other students. Unfortunately, some research has labeled EL students in static, deficit terms (e.g., not recognizing that language proficiency can change over time and be measured across a continuum), portraying their linguistic practices (i.e., speaking another language at home and being bilingual or multilingual) as detrimental to their academic success.

- Variations in data collection methods across various organizations and institutions have limited and created difficulties in conducting research on ELs in college.27 Typically, data on linguistic background are available in national longitudinal data sets (e.g., Education Longitudinal Study [ELS], Beginning Postsecondary Students Study [BPS], and High School Longitudinal Study [HSLS]) but may not exist or be reported in the same way in institutional data sets. In addition, K–12 institutions may have richer data than statewide databases and higher education institutions. Thus, because of the misalignment of how data have been collected or managed across P–12 and higher education at the federal, state, and institutional level, the capacity to analyze ELs’ experiences and outcomes along the P–16 continuum has been variable and limited. These factors affect the lack of scholarship for ELs in high education, and as argued by Nuñez et al., the transition to college for ELs is a complex process that is currently understudied.28

AB 705 also had an impact on policies related to credit ESL coursework because only one third of degree-seeking students who began in ESL coursework completed transfer-level English composition29 within six years, with even lower rates for those students placed into lower levels of ESL.30 AB 705 led to amendments to Education Code §78213 (d)(1)(E), which now states that colleges “must maximize the probability that … [a student enrolled in ESL] will enter and complete degree and transfer requirements in English within three years.”31 CCs were expected to fully implement AB 705 for ESL by fall 2020, but this was extended until 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.32 In addition, the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO) provided colleges curricular guidance for their ESL sequences:

- Consider integrating skills (e.g., grammar/writing, reading/writing, or reading/writing/grammar) in credit ESL courses (in lieu of stand-alone courses).

- Develop ESL Pathways, so students transition from ESL directly to gateway English rather than developmental English courses.

- Place students in ESL Pathways that have the highest probability of gateway English completion.

- Allow faculty teaching credit ESL courses to teach gateway English to students who have taken ESL courses or create an ESL course that is equivalent to gateway English.

- Increase professional development opportunities for faculty who teach credit ESL and gateway English.

- Pursue general education transfer credit (e.g., with California State University and University of California) for additional transfer-level ESL courses and areas beyond just composition.33

Each California CC has local control over curricular matters. They have the authority to respond to AB 705 by designing and implementing placement processes and curricula to optimize gateway English completion within 3 years for students entering the ESL sequence. Historically, ESL sequences have varied considerably across California CCs. In reviewing ESL sequences across the California CCs between 2010 and 2017, Rodriguez et al. describe these variations with considerations for sequence length (how many levels until gateway English), sequence type (instructional characteristics of ESL courses), and sequence endpoint (whether ESL Pathways lead to gateway English, developmental English, or transferable ESL).34 The implementation of AB 705 has influenced and will continue to influence how California CCs design their ESL sequences to ensure that students experience transfer-level English completion within a 3-year time frame.

In light of AB 705, research has been conducted to identify practices and structures supporting efforts to increase gateway English completion for students taking ESL courses. In an analysis of degree-seeking students within the ESL sequence enrolled between 2010 and 2012, Rodriguez et al. identified shortening sequence length and developing more ESL courses that utilize an integrated approach towards language skill development as potentially effective strategies to increase the likelihood of transfer-level English completion.35 They also found that ESL sequences that contain transferable ESL coursework support transfer-level English completion for students. Their findings suggest that there are strategies that can be helpful to support students’ likelihood of completing gateway English and highlight the importance of conducting data disaggregation to identify differences in outcomes experienced by different subgroups of CC students.

Research and policies relating to maximizing English outcomes for EL students in college are complicated by the fact that EL students transitioning from high school may pursue coursework in either the English or the ESL Pathway. While a student may be designated as an EL during their time in the California K–12 system, currently there is not a standard definition of an EL established by the CC system. This means that there is both fluidity in the curricular pathway taken for degree- or transfer-seeking ELs and a lack of a standard way to monitor or track the progression of cohorts of EL students towards the objective of completing gateway English. These realities have presented barriers and challenges to researchers in understanding how this population of subgroups of ELs experience English and ESL coursework within the CC system.

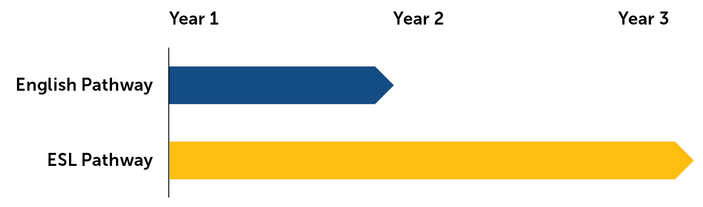

Ultimately, the intent of AB 705 is to increase the number of degree- and transfer-seeking students that complete this key gateway English class (i.e., transferable college-level English composition). Broadly speaking, there are two primary pathways towards achieving this goal in the California CC system that are both allowable under AB 705 and CCCCO guidance: the English Pathway and the ESL Pathway. ELs may experience either pathway depending on the placement and assessment systems in place when they enter college. These assessment and placement systems vary from college to college in California due to the policy of local control. For the purposes of this brief, an English Pathway is a sequence of English composition courses that lead to the completion of gateway English composition within 1 year. Prior to AB 705, the English sequence could be up to five courses deep; with the implementation of AB 705 in fall 2019, all students with a US high school GPA must be placed directly into the gateway English class. The ESL Pathway is defined as a sequence of ESL coursework and the completion of gateway English composition. Colleges are required to maximize the likelihood that students on this pathway will complete the gateway English composition class (or its equivalent) within 3 years (see Figure 1). Colleges are figuring out what data markers and decision rules should be used to place ELs in English/ESL Pathways that will maximize throughput. Regardless of colleges’ default placement structures and policies, ELs have the right to access the ESL Pathway. At this time, there are no data markers that would predispose colleges to direct certain students to the ESL Pathway. Given that ELs may experience either the English or ESL Pathway upon entry to the CC, strictly reviewing research on the ESL Pathway is insufficient for understanding the academic trajectories of ELs.36

Figure 1. Timeline to Complete Gateway English by Pathway per AB 705

The Impact of AB 705 on US High School Graduates who are ELs

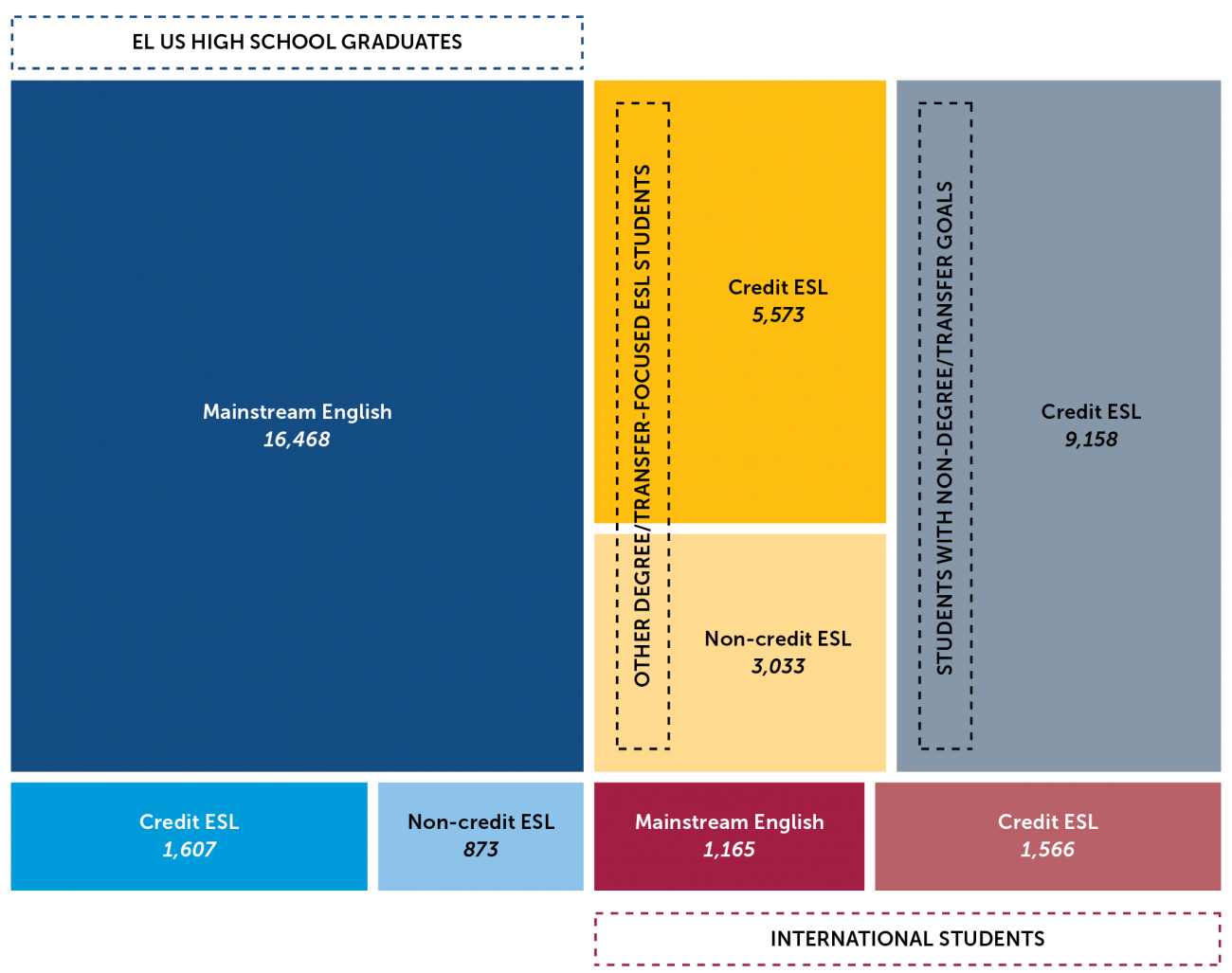

In addition to considering ELs’ entry into either the English or the ESL Pathway, there are multiple dimensions of the EL population that may influence how students experience English and ESL Pathways and their ability to achieve gateway English completion. One way to think about this population is to consider whether first-time degree- or transfer-seeking ELs are US high school graduates, international students, or neither. Figure 2 shows the relative size of different groups of ELs who took their first English or ESL class in the California CC system in 2017–18. When disaggregating data in this way, we know that nearly half (48 percent) of first-time, degree- or transfer-seeking ELs are US high school graduates. Given the prevalence of ELs that are US high school graduates, this brief examines the throughput rates of this subgroup once they enter CCs in California, with considerations of additional dimensions, such as estimated English proficiency, high school GPA, or ethnic/racial group, to better understand how this population may experience success in the English versus ESL Pathway.

Figure 2. Relative Sizes of First-Time, English Language Arts Pathways for Degree/Transfer-Seeking EL and ESL CC Students, 2017–18

Source. Student-level high school and CC records from California’s intersegmental longitudinal data system, Cal-PASS Plus

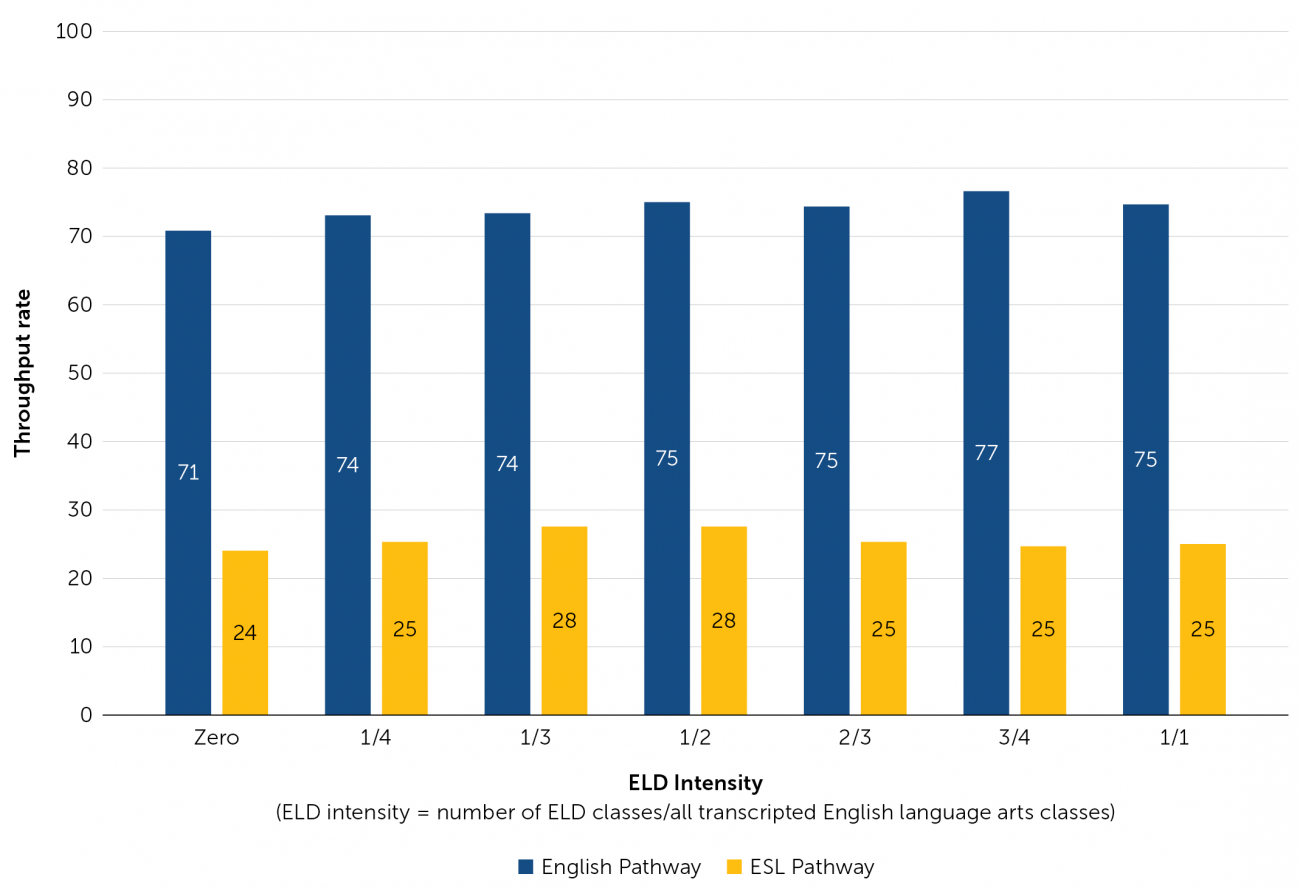

Although there may be misconceptions that ELs who are high school graduates may maximize their throughput rates via the ESL Pathway, prior research and our current analysis suggest this is not necessarily the case. Throughput rate is a relatively new metric that provides the percentage of a given cohort of students who complete a key gateway course—in this case, a transferable, college-level English composition course—within a designated time frame. In a recent paper from the RP Group’s Multiple Measures Assessment Project (MMAP), Hayward compared the throughput rates of students classified as ELs in US high schools and who subsequently enrolled in California CCs and entered either the credit ESL Pathway or the English Pathway.37

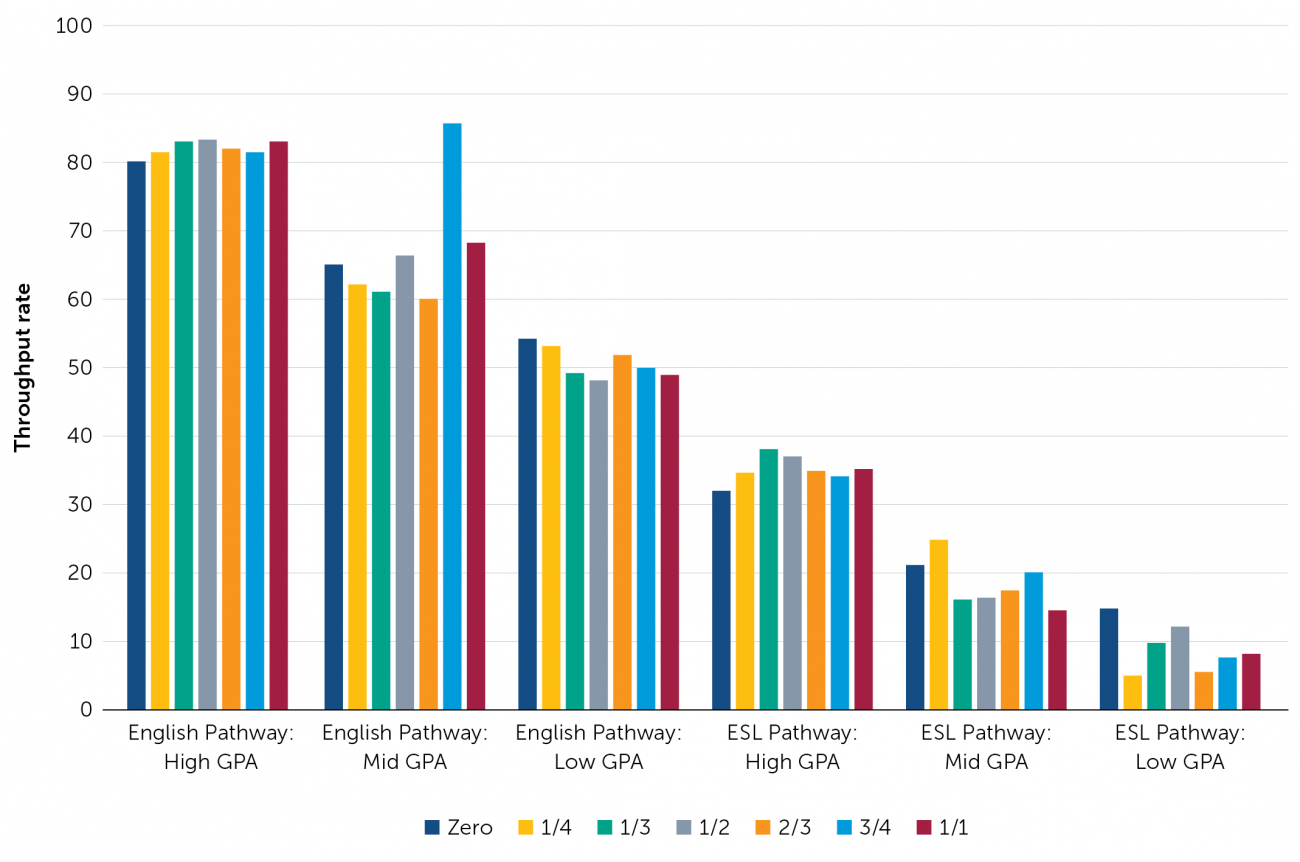

In our follow-up analysis of this data, we found that ELs who graduated from a US high school and then enrolled in the CC experienced much higher throughput rates when allowed to enroll directly in transferable, college-level English composition than if they were directed to the ESL Pathway.38 This relationship held true for all high school ELs regardless of their ELD intensity (i.e., the proportion of their high school English language arts coursework that consisted of ELD classes specifically designed to support the development of ELs’ English language proficiency; see Figure 3).39 At the high school level, beginning-level ELs tend to take more ELD classes than those at higher levels of English proficiency. However, students’ enrollment and placement in ELD courses may be influenced by factors unrelated to students’ English proficiency. Despite this limitation, for statistical measurement and modeling, ELD intensity can serve as a useful proxy for ELs’ English language proficiency levels in high school.

Figure 3. Throughput Rate by English or ESL Pathway Disaggregated by High School ELD Enrollment Intensity

Source. Student-level high school and CC records from California’s intersegmental longitudinal data system, Cal-PASS Plus

A competing hypothesis regarding these findings might be that the EL students who were high school graduates and had access to transferable, college-level English composition were systematically different from those who entered the ESL Pathway in a way not captured in Figure 3. High school GPA, for instance, is known to be a strong predictor of success in college.40 To control for the independent influence of variation in high school GPA, we disaggregated the students into three unweighted high school GPA bands (i.e., 0–1.89; 1.90–2.59; and 2.60–4.0). Even though there were strong effects for the variation in high school GPA, the entry into either the English Pathway or the ESL Pathway remained powerfully predictive of eventual throughput, so much so that our follow-up analysis found that students in the lowest high school GPA band who entered the English Pathway consistently achieved higher throughput rates than students in the highest high school GPA band who entered the ESL Pathway, across all ELD intensities (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. English Composition Throughput Rate Disaggregated by Pathway, High School GPA, and ELD Intensity

Source. Student-level high school and CC records from California’s intersegmental longitudinal data system, Cal-PASS Plus

Next, in our follow-up analysis to Hayward,41 we developed a multivariate model to simultaneously account for the influence of college entry point (English or ESL), high school GPA, ELD intensity, and ethnicity/race (Asian American, Latinx, neither). The model explained approximately 35 percent of the variability in throughput and correctly categorized the throughput outcome of 73 percent of the cases. The most powerful predictor of throughput was the pathway taken at the CC (i.e., English or ESL). The odds of EL US high school graduates who entered directly into transferable, college-level English composition successfully achieving throughput within 1 year of their initial enrollment in the sequence were more than 8 times greater than the odds of similar students who entered the ESL Pathway, controlling for the independent effects of high school GPA and ELD intensity as well as ethnicity/race. Latinx students were much less likely to achieve throughput than Asian American students, all other things being equal. Also, the higher a student’s intensity of engagement with ELD coursework in high school, the less likely they were to achieve throughput. However, this effect is not nearly as strong as the effects for the college language arts pathway taken (English vs. ESL) and for high school GPA.42

Policy Recommendations

1. Place ELs Who Are High School Graduates Directly in the English Pathway

Our findings clearly suggest that regardless of prior English language proficiency and academic preparation in high school, ELs placed in the English Pathway have better throughput rates and therefore have a greater likelihood of degree completion or transfer. Especially in the context of AB 705, remediation at CCs is only justifiable if it increases students’ chances of success in college. Our results indicate that requiring EL US high school graduates to take ESL courses will likely prolong their time to complete transferable, college-level courses and reduce their likelihood of succeeding in CC. In contrast, the data suggests that placing US high school graduates who are ELs directly into transfer-level English courses (e.g., the English Pathway) does not seem to overwhelm ELs. In fact, they are able to pass these courses without lengthy language remediation sequences. The combination of these two trends leads us to recommend that, by default, high school graduates who are ELs should be placed directly in the English Pathway—this is particularly justifiable if language support is incorporated into transfer-level English courses rather than isolated and sequenced, as in ESL courses (see our next recommendation).

2. Integrate ELD and Academic Instruction

The current CC system requires segments of the EL population to develop their English language proficiency to a certain threshold level before they are allowed to access college-level courses.43 We recommend that CCs move away from the current system wherein unreliable signs of English language proficiency such as EL status or ELD enrollment while in high school redirect students from the existing English curriculum in favor of a new system where English support is integrated into academic instruction throughout the college-level courses so that ELD and academic learning can take place in tandem. In other words, we recommend that at least some faculty be trained in evidence-based strategies and practices to embed language support into existing courses. Another possibility, especially in CCs where there is a critical mass of ELs from the same first-language background (Spanish, Chinese), is to offer some academic content courses in that language so that they can take college-level subject-matter courses in their first language—just as dual-language programs in K–12 education deliver academic content in two languages. These policies and practices will, in turn, increase EL students’ academic success and will allow them to persist and succeed in college and help create a culture in CCs that acknowledges and normalizes a rapidly growing number of multilingual students who are learning English and academic subjects at the same time. Such practices align with policy shifts in California’s K–12 system, where ELD coursework is integrated and is cohesive across students’ high school curricula. This presents an opportunity to create an ELD experience for ELs that is consistent, cohesive, and comprehensive at the K–12 and CC levels.

3. Track ELs’ Academic Pathways from High School to College in Administrative Data Sets

Absent other methods of identifying ELs, one way to identify ELs in the CCs has been to look at the students placed in ESL courses. Before the implementation of AB 705, it was already common for ELs, particularly those who graduated from high school, to begin on the English Pathway, leaving no indication in the administrative records of their status as ELs. Now, after the implementation of AB 705, it is even more common for ELs to begin in the English Pathway with a direct placement into transferable college-level English composition. Placement of more students directly on the English Pathway ironically further obscures recognition of multilingual students who may need language support. It is critically important, then, to improve data systems so that we may track ELs across the P–16 education span to understand their trajectories across educational systems. In particular, there is an urgent need to mend the fissure between high school and higher education so that students who were classified as ELs in high school (whether they were reclassified by the end of high school or not) can be tracked as they move into and through higher education, and their progress and success in college can be captured. California has already taken steps in this direction. Specifically, California’s new Cradle-to-Career Data System is beginning to connect existing education, workforce, financial aid, and social service information to help educators, decision makers and the public address disparities in opportunities and improve outcomes for all students throughout the state.

Specific data would be useful in this context and should be considered for collecting and sharing. First, it is possible to collect language data from college students when they initially apply for college. These data can mirror the Home Language Survey given to parents when students start their K–12 academic trajectory. Second, transcript, high school, and California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS; California Department of Education’s [CDE’s] longitudinal data system for state and federal reporting) data—including student-level records on EL and reclassification status—could be integrated into college and university data systems so that CCs and four-year institutions can assist in following ELs once they enter the system. The development and implementation of such a data system should also include policies and systems that foster data use in ways that support equitable outcomes. For example, using these data should not deter students’ access to the English Pathway in CCs but inform practitioners at the K–12 and CC levels. Counselors and advisors at both the K–12 and CC levels could use these data to inform and align how they develop, structure, and communicate the language arts coursework to and for students.

These data can provide insight into better alternatives to traditionally constructed ELD programs—whether bilingual classrooms, immersion with support, or integrated ELD across the curriculum. Knowing ELs’ curricular histories, such as ELD coursework and their relationship to CC gateway English completion, can assist in providing support and services to ELs as they navigate to and through their college experiences. Third, this data system presents an opportunity for CCs and four-year institutions to systematically and routinely collect data on the English proficiency of college students so that we can examine the educational and occupational trajectories of all groups of linguistically diverse students, including international students and non-degree-seeking ELs. Now is the time for California to ensure that ELs who transition from K–12 to higher education are adequately prepared and served.

- 1Mejia, M. C., Rodriguez, O., & Johnson, H. (2016). Preparing students for success in California’s community colleges. Public Policy Institute of California. www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/content/pubs/report/R_1116MMR.pdf

- 2In this brief, we define ELs as a subset of linguistically minoritized students who need support to access curricula in English. We use this definition for both students in K–12 education and in community colleges.

- 3Linguistically minoritized students refers to all students who consider a language other than English their primary language or the language that they speak at home. Importantly, not all language minority students need support to access English curricula since many of them are fluent in academic English. Nuñez, A.-M., Rios-Aguilar, C., Kanno, Y., & Flores, S. M. (2016). English learners and their transition to postsecondary education. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 31, pp. 41–90). Springer. See also Macías, R. F. (n.d.). Language minority students: Scope. education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2157/Language-Minority-Students.html

- 4LTELs are defined as ELs who have been enrolled in schools in the United States for 6 years without reaching levels of English proficiency that are needed to be reclassified.

- 5Buenrostro, M., & Maxwell-Jolly, J. (2021). Renewing our promise: Research and recommendations to support California’s long-term English learners. Californians Together. californianstogether.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Renewing_Our_ Promise_to_LTELs.pdf

- 6California Department of Education. (2021a). English learners in California schools. www.cde.ca.gov/ds/sg/englishlearner.asp; California Department of Education. (2021b). Facts about English learners in California. www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/cefelfacts.asp

- 7Contreras, F., & Fujimoto, M. (2019). College readiness for English language learners (ELLs) in California: Assessing equity for ELLs under the local control funding formula. Peabody Journal of Education, 94(2), 209–225.

- 8Bahr, P. R., Fagioli, L. P., Hetts, J., Hayward, C., Willett, T., Lamoree, D., Newell, M. A., Sorey, K., & Baker, R. B. (2019). Improving placement accuracy in California’s community colleges using multiple measures of high school achievement. Community College Review, 47(2), 178–211; Contreras & Fujimoto, 2019; Flores, S. M., & Drake, T. A. (2014). Does English language learner (ELL) identification predict college remediation designation? A comparison by race and ethnicity, and ELL waiver status. Review of Higher Education: Journal of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, 38(1), 1–36.

- 9Rodriguez, G. M., & Cruz, L. (2009). The transition to college of English learner and undocumented immigrant students: Resource and policy implications. Teachers College Record, 111(10), 2385–2418.

- 10Gebhard, M. (2019). Teaching and researching ELLs’ disciplinary literacies: Systemic functional linguistics in action in the context of US school reform. Routledge; Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching English language learners in the mainstream classroom (2nd ed.). Heinemann; Walqui, A., & Bunch, G. C. (Eds.) (2019). Amplifying the curriculum: Designing quality learning opportunities for English learners. Teachers College Press/WestEd; Rodriguez & Cruz, 2009.

- 11Recognition of this issue led to the passage of AB 2735, which prohibits middle schools and high schools from denying ELs participation in the standard instructional program of a school as of the 2019–20 academic year. Callahan, R., Wilkinson, L., & Muller, C. (2010). Academic achievement and course taking among language minority youth in US schools: Effects of ESL placement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(1), 84–117; Kanno, Y. (2021). English learners’ access to postsecondary education: Neither college nor career ready. Multilingual Matters; Kanno, Y., & Kangas, S. (2014). ‘‘I’m not going to be, like, for the AP’’: English language learners’ limited access to advanced college-preparatory courses in high school. American Educational Research Journal, 51, 848–878; Umansky, I. M. (2016). Leveled and exclusionary tracking: English learner’s access to academic content in middle school. American Education Research Journal, 53, 1792–1833.

- 12Kanno, Y., & Cromley, J. G. (2015). English language learners’ pathways to four-year colleges. Teachers College Record, 117(12), 1–46. Kanno and Cromley define English proficient students as those students for whom English is not their first language but who are already proficient in English.

- 13Kanno & Cromley, 2015.

- 14Llosa, L., & Bunch, G. C. (2011). What’s in a test? ESL and English placement tests in California’s community colleges and implications for US-educated language minority students. eScholarship. www.escholarship.org/uc/item/10g691cw; Woodlief, B., Thomas, C., & Orozco, G. (2003). California’s gold: Claiming the promise of diversity in our community colleges. California Tomorrow.

- 15Rodriguez, O., Bohn, S., Hill, L., & Brooks, B. (2019). English as a second language in California’s community colleges. Public Policy Institute of California. https://ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/english-as-a-second-language-in-californias-community-colleges.pdf

- 16Rodriguez et al., 2019.

- 17Bamford, K., & Mizokawa, D. (1991). Additive-bilingual (immersion) education: Cognitive and language development. Language Learning, 41(3), 413–429; Hakuta, K. (1983). New methodologies for studying the relationship of bilingualism and cognitive flexibility. TESOL Quarterly, 17(4), 679–681. doi:10.2307/3586621; Kanno, 2021; Nuñez et al., 2016; Rumbaut, R. G. (2014). English plus: Exploring the socioeconomic benefits of bilingualism in Southern California. In R. M. Callahan & P. C. Gándara (Eds.), The bilingual advantage: Language, literacy, and the labor market (pp. 182–205). Multilingual Matters.

- 18Rumbaut, 2014.

- 19Gándara, P. (2018). The economic value of bilingualism in the United States. Bilingual Research Journal, 41(4), 334–343.

- 20California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO). (2020). What is AB 705? assessment.cccco.edu/ab-705-implementation

- 21For the purposes of this brief, “remedial” and “developmental” education will be used interchangeably. Mejia et al., 2016.

- 22California Code of Regulations Title 5 (CCR-Title 5). Div. 6, Ch. 6, Subch. 6, Article 3 § 55522 (2019). govt.westlaw.com/calregs/Document/I3BBA08FE209543A9A8181F0BF33CD714?viewType=FullText&originationContext=documenttoc&transitionType= CategoryPageItem&contextData=(sc.Default)&bhcp=1; California Code of Regulations Title 5 (CCR-Title 5). Div. 6, Ch. 6, Subch. 6, Article 3 § 55522.5 (2020). govt.westlaw.com/calregs/Document/IB50561600DA042C099E9D38FC65DF7F2? viewType=FullText&originationContext=documenttoc&transitionType=CategoryPageItem&contextData=(sc.Default)

- 23Nuñez et al., 2016.

- 24Raufman, J., Brathwaite, J., & Kalamkarian, H. S. (2019). English learners and ESL programs in the community college: A review of the literature (Working Paper No. 109). Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University. ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/english-learners-esl-programs-community-college.pdf

- 25Linquanti, R., & Cook, H. G. (2013). Toward a “common definition of English learner”: A brief defining policy and technical issues and opportunities for state assessment consortia. Council of Chief State School Officers. files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED542705.pdf; Regan, A., & Lesaux, H. (2006). Federal, state, and district level English language learner program entry and exit requirements: Effects on the education of language minority learners. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 14(20), 1–32.

- 26Kanno, Y., & Harklau, L. (Eds.). (2012). Linguistic minority students go to college. Routledge. www.researchgate.net/publication/293201104_Chapter_1; Raufman et al., 2019.

- 27Nuñez et al., 2016.

- 28Nuñez et al., 2016.

- 29As in public discourse, this brief will use the phrases “transfer-level English,” “transfer-level English gateway,” “transferable college-level English composition,” and “gateway English” interchangeably.

- 30Rodriguez et al., 2019.

- 31Hayward, C. (2020). Maximizing ELL completion of transferable English: Focus on US high school graduates. The Research and Planning Group. rpgroup.org/Portals/0/Documents/Projects/MultipleMeasures/AB705_Workshops/Maximizing-English-Language-Learners-Completion_September2020.pdf; California Education Code Title 3 (EDC-Title 3). Div. 7, Pt. 48, Ch. 2 § 78213 (2020). leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?sectionNum=78213.&lawCode=EDC

- 32California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO). (2020, June 23). Emergency guidance for AB 705. static1.squarespace.com/static/5a565796692ebefb3ec5526e/t/60a7e5a2521b425e82f70cae/1621616038113/ES+20-24+Emergency+Guidance+for+AB+705+Implementation.pdf; California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO). (2018, July 20). Assembly Bill 705 initial guidance language for credit English as a second language. static1.squarespace.com/static/5a565796692ebefb3ec5526e/t/5b68e1ba70a6add62b06a9a9/1533600186421/AA+18-41+AB+705+Initial+Guidance+Language+for+Credit+ESL_.pdf

- 33CCCCO, 2018; California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO). (2019, April 18). Assembly Bill 705 and 1805 spring guidance language for credit English as a Second Language (ESL). assessment.cccco.edu/s/AA-19-20-AB-705-and-1805-Spring-2019-Guidance-Language-for-Credit-ESL.pdf; Rodriguez et al., 2019.

- 34Rodriguez et al., 2019.

- 35Rodriguez et al., 2019.

- 36While it may seem that some sort of proficiency test would be required in order to determine whether students should enter the ESL or the English Pathway, an analysis in Hayward (2020) of a subset of EL students who responded to the question “I am comfortable reading and writing English” found that even students who responded “No” to this question had much higher throughput when they entered the English Pathway. The same results were found for students who were still enrolled in ELD classes in 12 grade. Essentially, there is no marker in the institutional data that would provide a valid signal that a given EL US high school graduate should enter the ESL Pathway rather than the English Pathway.

- 37Hayward, 2020, pp. 12–14.

- 38It is up to the discretion of colleges and districts to determine how to best maximize timely gateway English completion per AB 705. As such, there may be variations in how students are advised/counseled into each respective pathway and how students are communicated their options (Hayward, 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2019).

- 39The greater a student’s ELD intensity, the less likely they were to enter the English pathway; 92 percent of students with no ELD classes (i.e., zero intensity) entered the English Pathway. That percentage dropped to 82 percent for those with one fourth intensity, to 71 percent for those with one half intensity, and to 55 percent for those with three fourths or full ELD intensity. In effect, ELD intensity in high school provides a signal of linguistic otherness that serves to direct students to the lower throughput ESL Pathway.

- 40Bahr et al., 2019; Scott-Clayton, J., Crosta, P. M., & Belfield, C. R. (2014). Improving the targeting of treatment: Evidence from college remediation. Educational Evaluation & Policy Analysis, 36(3), 371–393; Willett, T., Hayward, C., & Dahlstrom, E. (2008). An early alert system for remediation needs of entering community college students: Leveraging the California Standards Test (No. 2007036). California Partnership for Achieving Student Success.

- 41Hayward, 2020.

- 42These results are consistent with and build upon Hayward, 2020, whose findings suggest that EL US high school graduates had higher throughput rates in the English Pathway than the ESL Pathway, regardless of the number of years of attendance in the US high school. In other words, EL US high school graduates who began their US high school instruction in the senior year and then began in the English Pathway at CC had higher throughput rates than EL US high school graduates who had 4 years of US high school instruction and began in the ESL Pathway at CC.

- 43David, N. E., & Kanno, Y. (2020). ESL programs at US community colleges: A multi-state study of placement tests, course offerings, and course content. TESOL Journal, 12(2), e562.

Hayward, C., Kanno, Y., Rios-Aguilar, C., & Vo, D. (2022, June). English learners' pathways in California’s community colleges under AB 705 [Policy brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/english-learners-pathways-californias-community-colleges-under-ab-705