Collaboration and Addressing Student Needs

Summary

COVID-19 has disrupted California’s education system in fundamental ways. Districts across the state are quickly creating strategies to serve all students, and many are designing their response around the needs of their most vulnerable students. This brief highlights the response of Mother Lode Union School District (MLUSD) to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which district staff and teachers were able to collaborate—despite the unprecedented crisis—to meet student needs.

Introduction

This brief highlights the response of Mother Lode Union School District (MLUSD) to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which district staff and teachers were able to collaborate despite this crisis to meet student needs. Teachers, administrators, and staff came together to distribute devices and meals to students and families. In addition, MLUSD sought to ensure that their efforts would reach their most vulnerable students.

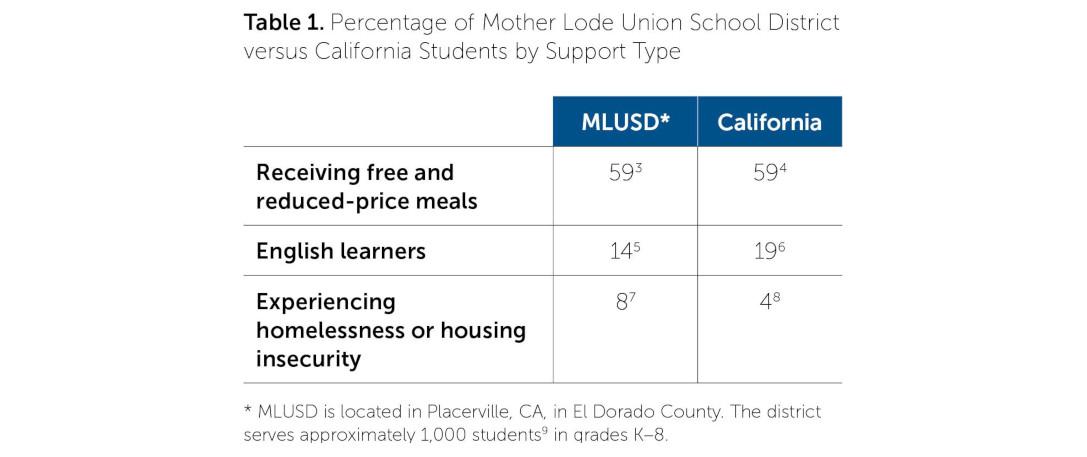

MLUSD is located in the Sierra Nevada foothills in rural El Dorado County and encompasses the region halfway between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe. The district’s name is a nod to its gold rush history; the region is known for its old-growth forests, its vast public lands popular with backpackers, and its rolling hills. At the same time, the region is home to deep rural poverty: nearly 60 percent of the students attending MLUSD’s two schools receive free and reduced-price lunches. The district covers 62 square miles.

Collaborative Spirit Lays the Groundwork

Crises test interpersonal relationships, and collaborative relationships are key in moments like this. Leaders in MLUSD have fostered a spirit of collaboration that predates this crisis and that has paid off during their response to the pandemic. Fortuitously, new leaders representing both the California Teachers Association and the California School Employees Association, along with the MLUSD superintendent and chief business official, attended the California Labor Management Initiative in February 2020. Their experience provided a new framework and expanded the forum for collaboration.

During this crisis, MLUSD leaders described collaborative work styles and positive relationships across the district. For example, Dr. Sadie Hedegard, Director of Student Support Services, shared: “I would say I’m really pleased [with how well the team is working together], and hope that other schools are experiencing what we’re experiencing with our team.” Superintendent Marcy Guthrie agreed: “We worked through those memorandums of understanding [to plan for distance learning], and have agreed that it’s so important to work together. This is an unprecedented time.” Teachers, staff, and administrators were able to build on their years of collaborative relationships and to focus their energies on serving students, rather than on managing or diffusing tensions among adults.

Reaching as Many Students as Possible While Considering Equity Implications

Across the state, districts have mobilized to meet their students’ basic needs. The leaders of this small, rural district were aware that many of their students would not have enough to eat or have internet-ready devices at home, so they set out to ensure that any student or family who wished to would be able to access what they needed. MLUSD leaders planned with equity in mind in order to ensure that their most vulnerable students would have access to services. They did so while making plans to distribute food and devices, and also while planning for and using tech platforms to deliver instruction virtually.

Distributing Food and Devices. In response to the COVID-19 closures, MLUSD’s teachers, administrators, and staff mobilized to distribute meals and Chromebooks to students and families. The district was eager to ensure that vulnerable students’ basic needs would be met in order to eliminate inequitable barriers to distance learning. Families were able to pick up both food and devices at Indian Creek Elementary School, one of the district’s two school sites. The district distributed approximately 200 meals per day, 5 days per week on average—serving one fifth of the district’s students while the schools remained closed (prior to COVID-19, 59 percent of students were eligible for free and reduced-price meals, see Table 1). District teachers and staff distributed Chromebooks to nearly 770 students— approximately 75 percent of students in the district. While the district also handed out dozens of internet hotspots, administrators estimated that 5 percent of students still did not have internet access at home, so teachers also prepared biweekly packets for these students to complete. This process ensured that students who would not be able to access online coursework would still have access to instructional materials.

When approaching this work, Dr. Guthrie stressed an equitable mindset that ensured the broadest possible participation. She said:

People who live in the hills have a lot of pride, which is a really positive thing. That means that if there is a need, they don’t want to take [a Chromebook, hotspot, meal] if someone needs it more than they do. And so what we’ve tried to convey is that we have Chromebooks for everyone in the district."

The MLUSD team also worked to ensure that food was available for students who live in remote rural areas and may not have been able to travel easily to the meal distribution point. During a discussion about meal distribution, a counselor noted that students who live in a particularly remote mobile home community might not be able to travel to the school site for food. In order to deliver food to these students, two bus drivers drove a van to the mobile home community several times a week, and students and families met them at their typical bus stops. Bobbi Lujan, the district’s nutrition services supervisor, said: “Our bus drivers are the best nutrition services helpers. They’re jazzed and ready to go.” Programs like this foster equity by meeting the needs of the most vulnerable and remote students.

Planning for and Using Tech Platforms. MLUSD leaders set out to ensure an equitable transition to distance learning for students by planning for their most vulnerable students first, deploying a key tenet of the “targeted universalism” approach. Dr. Hedegard explained:

First, we established what is the most accessible [distance learning] platform. We started thinking about our most vulnerable students. For the students with the most significant learning disabilities on our campuses, whichever platform would be most appropriate for them, that would be most accessible for general population as well."

With this mindset, the district settled on Google Classroom as its primary distance learning platform. In MLUSD, all teachers provided first instruction via prerecorded video, and were also available for office hours and organized small-group classes for guided practice. All teachers assigned daily or weekly tasks and provided students with feedback. However, this feedback did not translate to typical grades: spring 2020 grades were given as pass/no pass.

Teams of educators used Google Classroom to provide services to special education students: for example, a student might have been assigned to listen to a prerecorded social story about calming strategies read by a counselor before turning to a live reading lesson provided by a teacher or instructional paraprofessional.

Google Classroom also allows general education teachers to add special education teachers, a counselor, or a school psychologist as coteachers to the same “classroom” online, paving the way for instructional teams to review individual lesson plans to ensure that they incorporate principles of universal design for learning. For example, in an ideal plan during this period, a student receiving special education services might have logged onto Google Classroom and received the same information via a video and in writing at an appropriate grade level. This would have been supplemented by video conferences in Zoom or Google Hangouts, through which students could connect with specialists or aides. Instructors were expected to meet with special education students remotely one-on-one or in small groups.

The district used Google Sheets and online intervention programs, such as ReadLive, to plan and track delivery of services for students with disabilities, which allowed the district to track progress on Individualized Education Program goals at the end of the semester. Teachers, staff, and administrators who work with special education students followed schedules to better plan and deliver direct services—including specialized academic instruction, speech and language therapy, and occupational therapy— ensuring that students did not miss general education instruction to participate in a special education service.

MLUSD’s team worked to ensure that all teachers knew how to use the platform with all of their students: all teachers completed Google English language learner and accessibility training on the platform by the time distance learning officially began. This aimed to ensure that students would not face barriers to the platform based on their language spoken or status as a student with a disability.

Dr. Guthrie noted:

Something that was effective, efficient, and powerful was how the school site principals used Google Classroom with their teachers to teach them how to use it and other online resources. Teachers reported they learned a lot from this experience and from their colleagues."

Using Data to Explore Student Engagement

Once distance learning launched, central office staff monitored and applied data about student attendance and technology needs in order to understand the extent to which individual students were engaging in remote learning. District staff created lists of which students had logged on and which students had received technology, and teachers used this data to determine which students were not accessing the content. They then developed plans for getting content to students, including making hard copy packets and distributing them to students’ homes. As Dr. Hedegard noted, teachers “play a critical communication [role] in the collaborative effort.” For example, when a student received a new resource from the district—such as a Chromebook or hotspot—their teacher was encouraged to schedule a conversation with the family to discuss how to make the best use of it in their home.

The district determined a process to follow up with any students who were not engaging in distance learning. Twice a week, teachers reached out to the families of any students who were not logging on at all. In cases where a teacher was not able to make any contact with the family, they informed their school site administration. When school site or district administration were not able to make contact with the family, an administrator or a representative from the local Sheriff’s department visited the family for a wellness check. These visits have been a longstanding tool of the district, which has collaborated with the local Sheriff’s department for years in order to reach students who were missing school. Fortunately, during spring 2020 COVID-19 closures, only a handful of these visits were necessary. Some of the visited families left the district or sent students to temporarily live with extended family. If the family was available to speak with the representative making the wellness check, Dr. Hedegard explained that “it’s just making sure that everybody is safe and healthy. You’re asking them questions to learn what their challenges are and collaboratively find solutions.” During the visits, families identified internet access or lack of time to support distance learning as barriers. As a result, the district problem-solved with these families to identify services to fill these gaps.

Teachers monitored which students were participating online, their level of engagement and learning, and whether students were completing assignments. This data was collected and analyzed at the classroom level; it was not shared across schools or the district.

Looking Ahead to Fall 2020

What does fall 2020 hold? In May 2020, the district sent a survey to families to determine how many students will be returning to the district in fall 2020, and to assess what families’ concerns might be. The district is working with their nurse to plan ahead: How many kids, for example, could fit on an appropriately physically distanced school bus?

Dr. Hedegard suggested that the district may have to prepare for a blended approach that combines elements of distance learning with less frequent in-person classes in order to mitigate disease transmission. She is optimistic that such a blended learning model could serve students well, sharing: “I’m very hopeful that this will empower the school system, and engage students to foster learning.”

Superintendent Guthrie shared a similar sentiment, observing: “I think we’re going to come out of this as better educators, because we can incorporate ... myriad ... tools for our students.”

As the 2019–20 academic year ended, administrators and leadership from both teachers’ and classified unions met to plan for the coming school year. The district solicited feedback from staff on its current distance learning plan, should it need to be used again in fall 2020, and also began developing a blended learning plan that would include both in-person and remote instruction. The district is prepared to assign students standardized academic grades (rather than pass/no pass) in fall 2020.

Lessons Learned from Mother Lode Union School District

- Collaborative relationships between administrators, teachers, district staff, and county offices of education can facilitate transitions during times of crisis and these relationships can be built. Once COVID-19 is behind us, districts will continue to face unexpected crises. When adults work well together, they are able to more quickly respond to these events, and are therefore better positioned to serve students. It is a worthwhile investment of time and resources to strengthen these relationships in times of relative quiet.

- Planning for equity is possible even in the midst of a crisis. MLUSD leaders were able to both consider their entire student body and plan for their most vulnerable students when planning for distance learning. They did so using strategies that the district had long fostered, such as targeted universalism. Districts that plan for equity during quieter times will be better prepared to face crises in a way that mitigates barriers to learning for their most vulnerable students.

Endnotes and explanatory notes can be found in the full brief here.

Melnicoe, H., & Kaura, P. (2020, June). Collaboration and addressing student needs: A rural district’s response to COVID-19 [Practice brief]. Policy Analysis for California Education. https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/collaboration-and-addressing-student-needs