Summary

Absenteeism soared in California and nationally in the wake of the pandemic, and addressing this extraordinary increase is crucial to helping students catch up academically. Using data available from the California Department of Education and building on prior analysis, we examine trends in chronic absence (students missing school more than 10 percent of the time) through school year 2023–24. Although rates of chronic absence have continued to decrease since their peak in 2021–22, they remain alarmingly high. Ensuring equitable opportunities to learn will require ongoing attention and action.

Summary

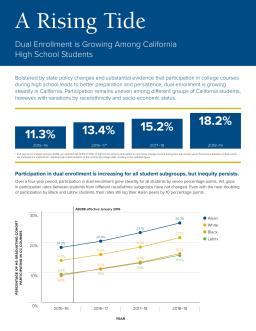

California policymakers and educators are promoting dual enrollment to boost educational attainment and equal access to postsecondary opportunities. Assembly Bill 288, enacted in 2016, encouraged high school-community college collaboration, and funding for dual enrollment has increased. Local educators are working to expand programs and support student success. Participation grew steadily from 2015–16 to 2019–20, but stalled in 2020–21 and 2021–22, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on dual enrollment opportunities.

Summary

Within the TeachAI Policy Workgroup, PACE has facilitated the development of AI policy informational briefs aimed at ensuring the effective, safe, and responsible integration of AI in education. These briefs offer guidance to education leaders and policymakers, emphasizing the importance of crafting policies that prioritize teaching and learning. The briefs provide insights derived from current research and landscape analysis of AI use in TK–12 educational settings, addressing common questions and centering around five guiding principles for developing responsible AI policies in education.

Summary

This infographic, from PACE and Wheelhouse, examines participation in dual enrollment among 9th to 12th graders. The data show that about 10 percent of all California public high school students enrolled in community college courses in 2021–22, but these rates vary from zero to 97 percent depending on locality. Analysis demonstrates that dual enrollment participation is unequally distributed across racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups as well as geography. The evidence demonstrates the potential of improving early access to dual enrollment in 9th grade for closing these equity gaps.

Summary

Chronic absenteeism has soared in California and nationally in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and addressing this extraordinary increase is crucial to helping students catch up academically. Using data available from the California Department of Education, this analysis examines trends in chronic absenteeism through school year 2022–23.3 Although rates of chronic absence have begun to decrease, they remain alarmingly high. Ensuring equitable opportunities to learn will require ongoing attention and action, including taking into account these seven key facts.

Summary

Summary

Summary

This report examines California's Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) after eight years and suggests refinements to improve equitable funding, opportunities, and outcomes. Based on interviews, research, and data analysis, the report identifies four areas for improvement: revisiting and refining the funding formula, modernizing funding for students with disabilities, equitably distributing effective teachers, and strengthening transparency, engagement, and accountability. LCFF has been viewed as an improvement over the previous system yet gaps between equity goals and local outcomes remain.

Summary

Summary

Summary

Summary

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all students; however, its impact has been particularly devastating for students of color, students from low-income families, English learners, and other marginalized children and youth. As transmission rates decline and vaccination rates increase in California, many are eager to return to normalcy, but we must all recognize that even the prepandemic normal was not working for all students. The 2021–22 school year, therefore, constitutes a critical opportunity for schools to offer students, families, and educators a restorative restart.

Summary

Summary

Summary

California is the wealthiest state in the US, yet its school funding is insufficient to meet educational goals due to the high cost of living. A series of 12 charts provide an explanation of what is happening, with solutions outlined in the final section of an accompanying report.

Summary

California schools' funding had improved, but still fell short of what is necessary to meet the state's goals. Now, schools face three major challenges: declines in student achievement and social-emotional well-being due to COVID-19, increased costs associated with distance learning and school reconfiguration, and the need to tighten budgets. Securing necessary funding will require an enormous and sustained effort from many stakeholders to improve schools and student outcomes and strengthen the economic and social outlook for future generations.

Summary

Summary

Parental engagement is essential to improve academic outcomes for all students, particularly low-income, Black, and Latinx students. Distance learning has intensified the need for parental support, but state policies and tools for engagement are inadequate. Local Educational Agencies can remove barriers to data access and support parent engagement by following three key principles and taking related actions.

Summary

How can schools provide high-quality distance and blended learning during the pandemic? This brief includes a mix of rigorous evidence from extant studies, data from interviews with practitioners who described their learnings from informal experimentation during the spring of 2020, and expert researchers who thought about how to apply research to the current context.

Summary

Summary

This suite of publications provides 10 recommendations based on the PACE report to help educators and district leaders provide high-quality instruction through distance and blended learning models in the 2020-21 school year. Despite the challenges of COVID-19, research can guide decisions about student learning and engagement. These recommendations can be used as a framework to prioritize quality instruction.

Summary

Summary

In the run-up to 2020 elections, where do California voters stand on key education policy issues? This report examines findings and trends from the 2020 PACE/USC Rossier poll. Key findings include rising pessimism about California education and elected officials, continued concern about gun violence in schools and college affordability, and negative opinions about higher education. However, there is substantial support for increased spending, especially on teacher salaries.

Summary

The 2018 Getting Down to Facts II research project drew attention to California’s continued need to focus on the achievement gap, strengthen the capacity of educators in support of continuous improvement, and attend to both the adequacy and stability of funding for schools. Based on the nature of the issues and the progress made in 2019, some clear next steps deserve attention as 2020 unfolds.